University Press of New England Hanover and London

University Press of New England

www.upne.com

2012 John Barylick

All rights reserved

MAMA TOLD ME NOT TO COME

Words and Music by RANDY NEWMAN

Copyright 1966, 1970 (Copyrights Renewed) UNICHAPPELL MUSIC INC.

All Rights Reserved Used by Permission

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barylick, John.

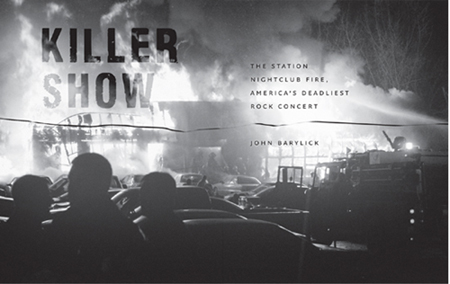

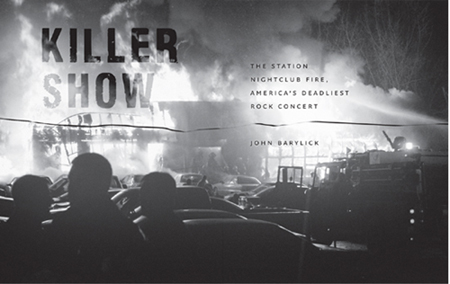

Killer show : The Station nightclub fire, Americas deadliest rock concert / John Barylick.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61168-265-6 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-61168-204-5 (ebook)

1. Station (Nightclub : West Warwick, R.I.)Fire, 2003. 2. NightclubsFires and fire preventionRhode IslandWest Warwick. 3. FiresRhode IslandWest Warwick. 4. Great White (Musical group) I. Title.

F89.W4B37 2012

974.5'4dc23 2012002561

FOR THE VICTIMS

Its gonna be a killer show.

Jack Russell, lead singer of Great White, February 20, 2003

killer adj. (orig. US) 1 [1970s+] terrific, amazing, effective.. 2 [1980s+] ghastly, terrible.

Cassells Dictionary of Slang, 1998

CONTENTS

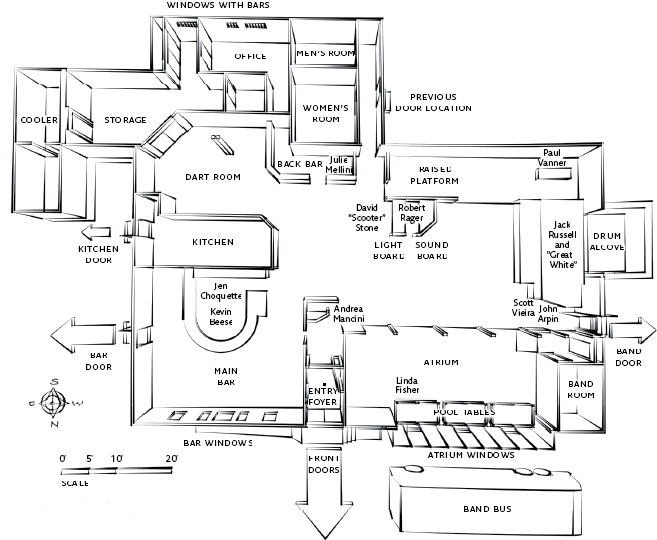

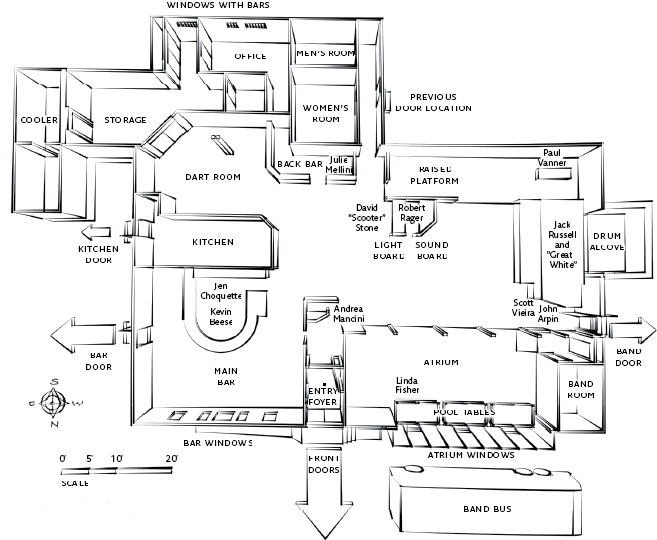

Floor plan of The Station, with location of individuals at 11 p.m. on February 20, 2003. (Diagram courtesy of Jeff Drake, Drake Exhibits)

CHAPTER 1

SIFTING THE ASHES

FEBRUARY 21, 2003, DAWNED STUNNINGLY CRISP and cold in New England. Over a foot of fresh snow had fallen the previous two days, and conditions were what skiers jokingly call severe clear cloudless blue skies, bright sun, temperatures in the teens, and windchill in single digits. It was, in short, postcard picture-perfect.

On this morning, however, the images being snapped by news photographers in the town of West Warwick, Rhode Island, were hardly Currier and Ives material.

In the southeast corner of town sat a nightclub called The Station or what was now left of it. At present, it consisted of a smoldering footprint of rubble at the end of a rutted parking lot, surrounded by banks of dirty snow into which burning bar patrons had blindly thrown themselves just eight hours earlier. The site resembled the scene of a battle, fought and lost. Discarded half-burned shirts littered the lot, along with soiled bandages and purple disposable rescuers gloves. Hearses had long since supplanted ambulances, the work of firefighters having shifted from rescue to recovery.

Alongside the smoking remains of the club, a hulking yellow excavating machine gingerly picked at the buildings remains. Its operator had demolished many fire-damaged buildings before, but none where each pick of the claw might reveal another victim.

Yellow-coated state fire investigators and federal agents wearing ATF jackets combed the scene, while a department chaplain divided his time between consoling first responders and praying over each body as it was removed. Only snippets of conversation among the firefighters could be overheard, but one bodies stacked like cordwood would become the tragedys reporting clich.

And there was no shortage of reporters covering the fire. By late morning, over one hundred of them huddled in a loose group at the site, faces hidden by upturned collars, their steamy exhalations piercing the frigid air at irregular intervals. Stamping circulation into their cold-numbed feet, they awaited any morsel of news, then, fortified, drifted apart to phone in stories or do stand-ups beside network uplink trucks.

Following protocol, all but designated spokesmen avoided contact with the press. The area had immediately been declared a crime scene, and yellow tape, soon to be replaced by chain-link fence, kept reporters far from what remained of the building itself. During the first daylight hours, news helicopters clattered overhead, their rotor wash kicking up ash and blowing the tarps erected by firefighters to shield the grisly recovery effort from prying eyes. That vantage point was lost after one chopper got so low it blew open body bags containing victims remains. Immediately, the FAA declared the site a no-fly zone. Good footage would be hard to come by.

That is, good post-fire footage. Video of the fire itself, from ignition to tragic stampede, had already been broadcast throughout the United States and abroad, because a news cameraman happened to be shooting inside the club. The world had seen the riveting images: an 80s heavy-metal band, Great White, sets off pyrotechnics, igniting foam insulation on the clubs walls; concertgoers festive mood changes in seconds to puzzlement, then concern, then horror as flames race up the stage walls and over the crowd, raining burning plastic on their heads; a deadly scrum forms at the main exit.

Now, all that remained were reporters questions and a sickening burnt-flesh smell when the biting wind shifted to the south. Among the questioners was Whitney Casey, CNNS youngest reporter, who just hours earlier had exited a Manhattan nightclub following a friends birthday celebration. Dance music was still echoing in her sleep-deprived head when she arrived at a very different nightclub scene in West Warwick. Casey had covered the World Trade Center collapse as a cub reporter on September 11, 2001. From its preternaturally clear day to desperate families in search of the missing, the Station nightclub fire assignment would have eerie parallels to her 9/11 reporting baptism.

It wasnt long before the sweater and jeans from Caseys crash bag (on hand for just such short-notice call-outs) proved a poor match for New Englands winter. Shivering alongside the yellow tape line, the CNN reporter spotted State Fire Marshal Irving J. Jesse Owens huddling with West Warwick fire chief Charles Hall. She heard questions shouted by her fellow reporters: Chief, how recently was the club inspected? What was the clubs capacity? Who put that foam up on the walls? Neither responded. Nor would anyone in authority answer those and other critical questions for a very long time.

State Fire Marshal Owens had the world-weary look of someone who had been investigating fires for thirty years. Thin of hair and pudgy of build, Owens had seen many fatal fires before. But none like this. He had to have heard the reporters shouted questions in the same way one hears his doctor prattle on after having first pronounced the word cancer as a faint sound drowned out by the rush of racing thoughts. Owens had a lot on his mind. Ten hours before the fire, he had given an interview to Bryan Rourke, a Providence Journal reporter, on the subject of a recent Chicago nightclub stampede in which twenty-one people had been killed. Its very remote something like that would happen here, opined Owens. Now he wondered whether the phone message he left for Rourke while on his way to the Station conflagration would stop that story from running. I guess we spoke too soon, he said in a dejected voice-mail postscript.