Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2022 by Stephanie Schorow

All rights reserved

First published 2022

E-Book edition 2022

ISBN 978.1.43967.663.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022943537

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46715.287.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the help of many fire professionals, Cocoanut Grove historians, survivors and families of survivors. My deepest thanks go to Casey Grant, Billy Noonan, Marty Sheridan, Charles C. Kenney, Jack Deady, Leo Stapleton, John Quinn, Jack Lesberg, Jane Alpert Bouvier, Paul Christian, Barbara Ravage, Kevin Richards and John Vahey for their recollections and expertise. I am grateful beyond words to David Blaney, who graciously shared his research with me; his meticulous work deserves a wider audience. Barbara Poremba was kind enough to share her research on nurses. It should be noted that Casey Grant, Barbara Poremba and David Blaney made major contributions to this book in the form of fact-checking and suggesting additional information. I am always thankful for the support of the Boston Fire Historical Society and its excellent web resources. Thanks to members of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee, including Michael Hanlon and Kenneth Marshall. Special thanks go to the late Paul Benzaquin for sharing his memories of writing his landmark 1959 book on the fire. I also want to thank former Boston Police archivist Donna Wells and the late attorney Frank Shapiro. Thanks to Anne DUrso-Rose for mental health information and links. Ronald Arntz provided me with some important photos of the club before the fire; Im so glad that our chance encounter on a boat in Boston Harbor brought us together. I am grateful to Nora Bergman, daughter of Goody Goodelle, and Meg Schmidt, daughter of Martin Sheridan, for sharing stories of their families and providing fact-checking. Thanks to Kathy Dullea Hogan for sharing the story of her fathers diary, Joseph Short for showing me the wallet of fire victim Joseph Tranfalia, Ina Cutler for telling me about her mothers death in the fire and Jim Cavan and Phyllis Capone Cavan for sharing their family history. I must thank Bob Shumway and his daughter Jackie Sexton and son Curtis Shumway for helping me arrange a Zoom interview with one of the last living Cocoanut Grove survivors. I no longer have her name, but I am incredibly grateful to the woman who stopped at my yard sale, told me she had photos of the fire and shared them with me so I could scan them before they were donated to the Boston Public Library. Much gratitude to Aaron Schmidt and Bob Cullum for helping me obtain permission to use photographs from the Boston Public Library and the amazing Leslie Jones Collection. Gratitude to Donna Halper for her research assistance on the 2005 edition. Thanks go to the librarians of the National Fire Protection Association, the Boston Herald, the Boston Globe and the Medford Public Library. I am grateful for the encouragement and guidance from Mike Kinsella of The History Press, who has been unerringly patient and helpful, and to Abigail Fleming for her excellent copy editing. I could not have completed this manuscript on time without input from my partner-in-crime-writing, Beverly Ford, an extraordinary friend and editor.

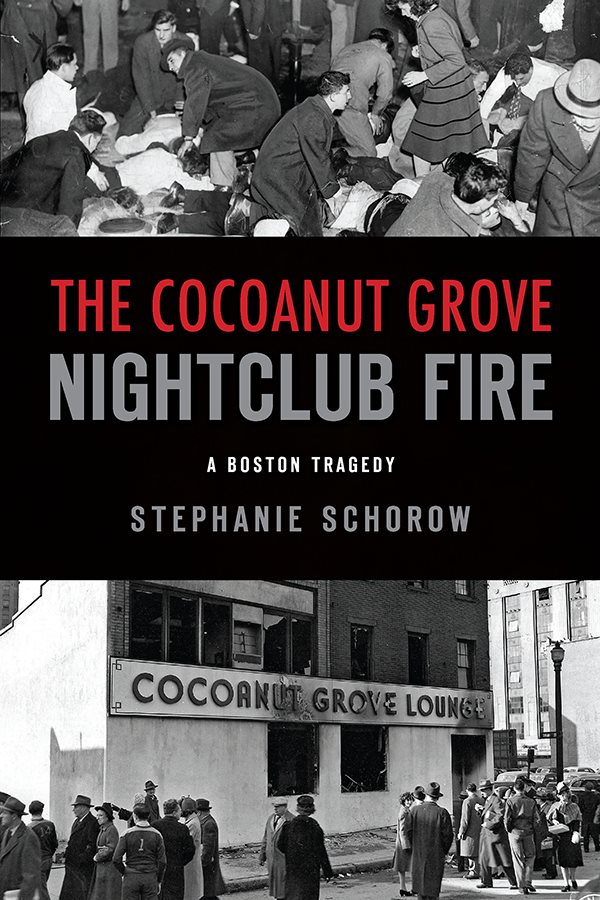

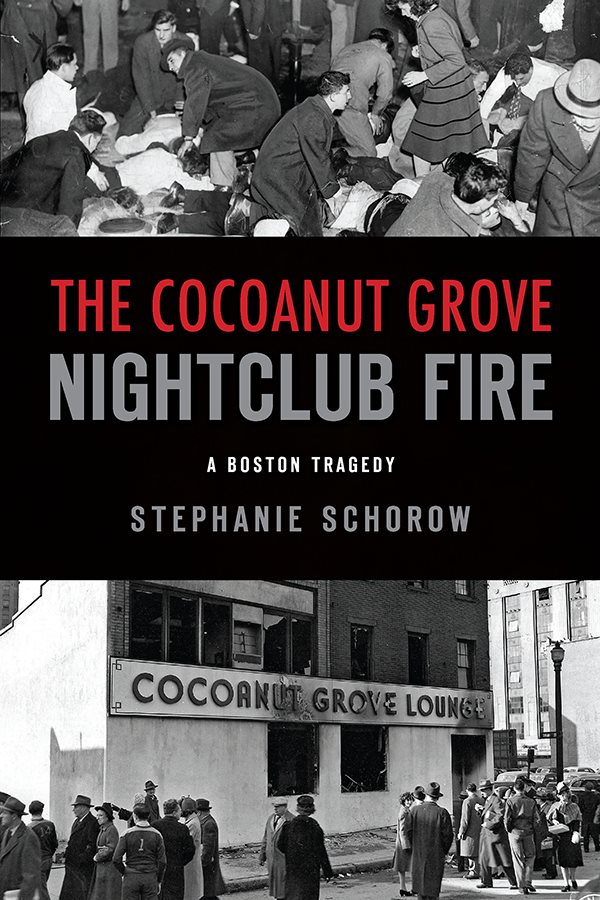

PROLOGUE

Outside, its bitter cold. Inside the nightclub, the joint is jumping. Anxious to take a break from the gloom of winter and the worries of war, crowds of peopleyoung and oldhurry along Piedmont Street, in the citys theater district, heading for the revolving door under the Cocoanut Grove sign that reaches toward the sky. They anticipate the loud buzz of conversations, the cocktail-fueled laughter, the air saturated with cigarette smoke and perfume. They will check their coats and stroll into the main dining room, a faux South Seas paradise in chilly Boston, with fake palm trees, rattan furniture and chairs decorated with a striking zebra pattern. Maybe theyll be luckythey might get seats in the area reserved for celebritiesa raised terrace set back from the main stage. Who knows who could be there? Cowboy star Buck Jones was in town, wasnt he? There was a new singer, tooDotty Myles, only a teenagerbut said to already be a star. Sure, it was expensivean order of half a dozen oysters was $0.40, broiled scrod was $0.80, a baked lobster set you back $2.25 and a tenderloin steak cost $2.00. But it was the Cocoanut Grove, after all.

A night on the town. That was the plan for many Bostonians on November 28, 1942that is, until they walked through the revolving doors and found the club too crowded for comfort and the heat too high for enjoyment. The coatroom was so full, coats were stacked on the floor. The dance floor was shrinking as waiters tried to squeeze even more tables into the main dining area. Disappointed, would-be merrymakers left to seek another club or restaurant or maybe call it a night. They would not realize until the next day how lucky they had been.

INTRODUCTION

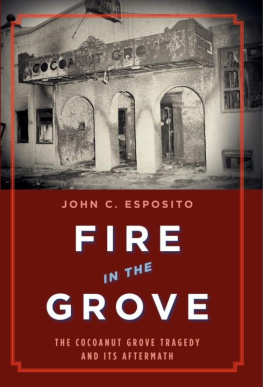

The night of November 28, 1942, is seared into the collective memory of Bostonians. A fast-moving fire roared through the popular Cocoanut Grove nightclub on what was meant to be a festive Saturday evening, leaving more than five hundred people dead, dying or maimed for life. The inferno reached deep into the citys social structureits politics, medical care, law enforcement and religious lifeand touched nearly everyone in the Boston area that day, even those who had never set foot in the club. Mention Cocoanut Grove to most longtime Massachusetts residents, and tales flood out of great-uncles and aunts who died in or escaped from the fire, of grandmothers who treated patients as nurses, of grandfathers who fought the blaze or relatives who, amazingly enough, were at the club that night but left early.

Yet for decades, many victims and witnesses could not speak of what they saw or experienced; their silence has helped build a mystique about the fire, an aura of a catastrophe too terrible to imagine.

In sheer numbers, the Cocoanut Grove falls short of the devastating 1903 Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago, which killed more than 600, and the collapse of the World Trade Center in a terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. But recall that the death toll of the devastating 1871 Chicago Fire, which spread over 3.3 miles, reached only an estimated 300 people. The Groves impact extends beyond mere statistics. Doctors and nurses, faced with the medical battle of their lives, developed better treatments for burns and lung injuriestreatments still in use today. By listening to Cocoanut Grove survivors, mental health experts gained insight into how trauma affects not only the body but also the mind. The fire led to tougher fire safety codes and more stringent enforcement of long-standing regulations. The investigation and subsequent trial defined the legal culpability of those who let expediency stand in the way of safety or do not maintain buildings properly.

Next page