Most of this book is from first-person interviews, conducted over the course of years. For the main subjects I used a multistep process for accuracy. After an initial interview, I would write up a scene told from that persons point of view, then return later with a printed draft to review each word. These additional sessions would often prompt vivid memories and became a key part of my reporting process.

Anything in quotation marks came from these interviews, or was captured on audio or video by other journalists. Other quotes are from official documents, including thousands of pages of transcripts from once-secret grand jury testimony. In rare cases I used quotes from conversations that my subjects remembered others saying with a high degree of certainty, but it is clear on the page that these are recollections from the subjects point of view. If someone was less certain about the exact wording of what was said, I summarized the comment, or used italics. Italics are also used to denote the internal dialog some remembered. No dialog was invented by me, and quotes were not altered or corrected for grammatical purposes.

News coverage of the fire is quoted or referenced if from a credible journalist or reputable news organization. Occasionally I will mention something reported that was journalistically questionable, but in those instances, it is clear thats the point.

Some people depicted in these pages could not be interviewed or given the opportunity to review pages for accuracy. References to how a deceased person acted, felt, or spoke are based on firsthand witness accounts, direct quotes, documents, or photos. I corroborated this information when possible, and if minor details were in dispute, they were omitted.

I have used occasional footnotes for the sake of transparency, such as showing the math that was used to calculate a fact, or to note when I have a personal connection to people or situations. I have several, since the events in these pages represent the worst thing to happen in the place where I grew up.

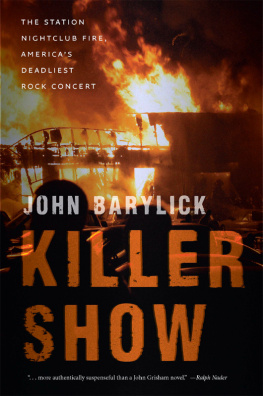

It takes ninety seconds to sing The Star-Spangled Banner. Human beings, on average, can hold their breath for up to ninety seconds. A typical person needs ninety seconds to read one page of this book.

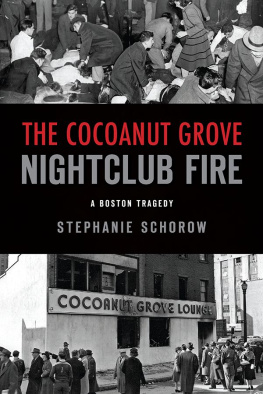

Ninety seconds marked the moment between life and death on the night of February 20, 2003, at The Station, a scruffy, low-slung roadhouse nightclub in the old New England mill town of West Warwick, Rhode Island.

Tragedy started with a song.

Shortly after eleven the rock group Jack Russells Great White took to the clubs stage with screeching guitars in the dark. On cue the bands tour manager Daniel Biechele set off four gerbsgiant sparklers set on the floor behind the lead singer, two blasting bolts of sparks to the sides and two in the middle directed up toward the clubs low, dark, glittered ceiling. The fireworks lasted seventeen seconds and were meant to evoke the aging metal bands former stadium glory days in the nineties, creating an ethereal glow behind the performers. The audience went wild.

The sparks ignited a small fire on the wall to the left of the stage. Nine seconds later a second trickle of flames appeared on the wall to the right of the stage.

Jeffrey Derderian, a local television news reporter and the clubs co-owner, his clean-cut appearance at odds in a sea of rockers, saw the flames from the corner of his eye. As usual, hed been too busy working the bar to watch the show, so his first thought was that something in the morass of sound equipment had caused an electrical fire. Jeffrey ducked under the counter and darted toward the stage and spotted soundboard operator Paul Vanner with a fire extinguisher in hand, also en route. Jeffrey pointed and barked, Get up there! Neither man could. The crowd was too thick, and as a deafening guitar riff raged, frenzied fans jumped up and down with their arms raised in the classic heavy metal tribute, a fist in the air with pinkie and forefinger extended. Rock on!

Great Whites forty-two-year-old lead singer, Jack Russell, belted out the opening lyrics of Desert Moon from the bands 1991 album Hooked. His microphone was upcut at first, set too low to be heard over the guitars, but then his voice filled the club, his tenor still powerful a dozen years after the bands prime. Lets shake this town, baby, come with me! I need a little loving company!

Sixteen seconds after the first flames appeared on the walls, the fire expanded and reached the ceiling.

The crowd in front of the stage kept raving, many believing the growing pyre was theatrics, a planned part of the show. They howled in appreciation. Some patrons in the back of the audience, however, sensed trouble and began to orderly evacuate.

Singer Jack Russell was unaware he was surrounded by danger, so he hit the next lyric, Come on, now, I know where we can go! Then he noticed the burning wall, stopped singing, and the band quieted. Wow. Thats not good, Russell said, deadpan, and picked up bottled water to toss at the wall to no effect. Hed halted just short of the verse, Ive got a fire like a heavenly light.

Thirty seconds had passed since the first flames appeared.

Two seconds later, like a lit match dropped into a pool of gasoline, the fire surged across the walls and ceiling.

As band members escaped through the stage door exitforty-one seconds after the fire startedthe nightclubs alarm blared, emitting an intense, piercing wail. Emergency strobe lights pulsated around the club. The siren signaled that the blaze was not part of the performance, and there was a sudden shift in the room. Panic. Patrons turned from the stage and raced toward the clubs main entrance, the door they had arrived through. Few headed for any of the three other exits. In the melee, the casual camaraderie of fellow concertgoers was replaced by a fight for survival. Get out of my way! a man shouted, shoving others aside.

Sixty seconds after the first trickle of flame, the stage was fully engulfed and then disappeared from sight, replaced by choking pitch-black smoke that plunged the club into darkness. A survivor later described the smoke as a thick, menacing blanket dropped over everyones heads.

With too many people trying to escape through one door, the stampede became a pile that made the exit impassable.

Ninety seconds after the fire started, the black haze reached the floor, smothering all inside. The building burst into a raging inferno and the night sky filled with jolts of flames and the sounds of explosions and terrified screams.

In ninety seconds nearly everyone still inside The Station nightclub was dead or dying. It was the deadliest single building fire in modern American history, and the nations deadliest rock concert. In the United States, where billions have been spent on fire prevention and protection, there should have been time to escape, to be safe.