Copyright 2007 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Peretti, Burton W. (Burton William), 1961

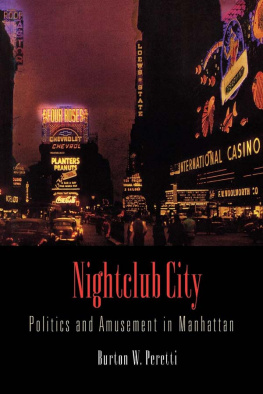

Nightclub city : politics and amusement in Manhattan / Burton W. Peretti.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-8122-2157-2

1. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)Social life and customs20th century. 2. NightclubsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 3. City and town lifeNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 4. LeisureNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 5. AmusementsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 6. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)Politics and government20th century. 7. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)Social conditions20th century. 8. New York (N.Y.)Social life and customs20th century. 9. New York (N.Y.)Politics and government18981951. 10. New York (N.Y.)Social conditions20th century. I. Title.

F128.5.P47 2007

2006051092

Preface

In 1926, on 54th Street in midtown Manhattan, the entertainer Mary Texas Guinans 300 Club glowed with color and resonated with activity. Stephen Graham, an Englishman, recalled his visit to the club with pleasure. The walls are covered with pleated cloth and the roof tented with the same cloth softly toned in old rose, green, and sere yellow. There are hanging Chinese lanterns, and on the walls illuminated designs of parrots. There are twenty or thirty tables and a small space in the middle of them for intimate dancing. The lighting is wonderful. A charming girl in blue satin trousers and wearing a crimson sash sold cigarettes while a smart girl in black with silver flowers on her hips dispensed gift dolls. A guitar quartet strolled amid well-heeled patrons such as Harry Thaw (the wealthy playboy famed for his murder of the architect Stanford White twenty years earlier) and the mayor of New York City himself, James J. Walker, flitting in elegantly to touch the hands of several of a large party and yield his charming smile to the ladies. Guinan, the mistress of ceremonies, appeared to introduce her near-naked girls and a song about cherries. Cherries! the crowd shouted. One girl put a cherry into each mans mouth. One took the cherry and kissed the girls fingertips. Another girl following ruffled up mens hair as she passed. A young man was recruited to dance with the chorines, the audience sang And She Knows Her Onions! and Guinan tossed finger-clappers and snowballs made of felt to the customers. The show concluded with a merry projectile fight. The hostess pelted a pair of newlyweds with rice and the clock struck five. One of the waiters borrowed a horn from the jazz band and blew dreadful reveilles into the ears of the sleepers. By sunrise, even Guinan herself had become sedate.

Shortly after Grahams visit, the 300 Club became a victim of official suppression. According to the New York Times, four hundred patrons were present that night, including two U.S. senators (whom the Times discreetly did not name) and twenty visitors from Georgia welcoming home the new champion of the British Open golf tournament, Bobby Jones (who was not at the club). Two New York City policewomen, dressed and acting as if they were visiting flappers seeking a thrill,

The short life of the 300 Club is part of the fascinating and important history of Manhattan nightclubs between World Wars I and II. This history illuminates important dynamics in American culture in these decades, such as gender relations, affluence, leisure, law enforcement, and urban commerce. Nightclub City explores these dynamics in one grand context: the interaction of nightclub leisure and civic life. The encounter between clubs and government generated scandals, reform crusades, and regulations that helped to redefine the realities and the images of urban life in the United States. In addition, through this interaction nightclubs also transferred some of their style and cachet to the texture of city politics. By 1940 nightclubs were closer to the respectable heart of civic life, and the dream-manufacturing operation of the leisure industry had insinuated itself into politics. Since then, to the present day, the interwar mating of clubs and politics has continued to influence the culture of the city and the nation.

From their inception in the early 1920s, nightclubs in midtown Manhattans theater district were celebrated as representative institutions of that roaring decade. Boisterous rooms filled with illegal liquor, female dancers, well-heeled revelers, and multiethnic employees, surrounded by a nightlife environment of speakeasies, Broadway street life, taxicabs, dance halls, and all-night restaurants, exerted a pull on the national imagination. African American Harlem and bohemian Greenwich Village provided uptown and downtown counterpoints, respectively, to antics in the theater district. In the mid-1930s, after the repeal of Prohibition and the passing of the worst of the Great Depression, the nightclub achieved a renewed prosperity and notoriety. Mostly because of the efforts of nationally syndicated gossip columnists and Hollywood musicals, the Manhattan nightclub remained an iconic presence in popular culture. Partly as a result of this, some clubs were able to survive the upheavals of the 1940s and stay in business for decades.

Previous histories of the nightclub have stressed two predominant themes. First, they have argued that the clubs popularity illustrated the decay of Victorian institutions and values after the turn of the nineteenth century. They have also especially noted the role of nightclubs in the evolution of race relations. Southern African Americans migrated to Harlem in large numbers during World War I and established its cabaret culture. In the 1920s, though, white managers and gangsters forcibly took over black-owned clubs and controlled the careers of black entertainers. Their campaign facilitated the vogue for Harlem among affluent white patrons. At the same time, though, civil rights advocates and artistic modernists were inspired by the pioneering and intimate interracial contact that the new nightlife encouraged.

My initial research into nightclubs strove simply to carry this story forward into the Depression decade of the 1930s. After a cultural institution reaches an apotheosis, it seemed logical to ask, does its influence wane and go into decline, especially if surrounding economic conditions worsen drastically? In such circumstances, in what direction would a nightclub rebellion against Victorian bourgeois domesticity and in favor of modern experimentation now go? Would depression Americawhich celebrated the common man and rural rootsencourage an antithesis of the classic nightclub, and perhaps a future synthesis of Victorian and modern values, of conformity and rebellion?

As the project progressed I maintained an interest in these questions, but I also increasingly found myself stretching the boundaries of the topic and searching for the broader relevance of the Manhattan nightclub story. I became particularly fascinated with clubs increasingly high profile as an object of social and political debate between 1924 and 1933. In these years, while literary figures such as Carl Van Vechten, Edmund Wilson, and Rudolph Fisher explored the implications of the nightclub experience for private sensibilities and social relations,