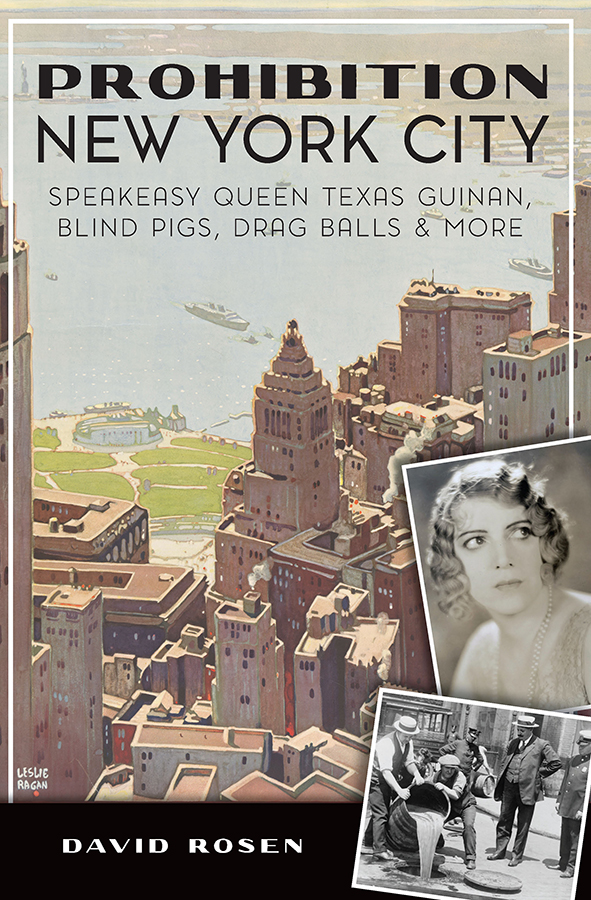

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by David Rosen

All rights reserved

First published 2020

e-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43967.174.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020941792

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.641.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

For Jessica and Isabela and Dara and Zachary, in the hope that the 2020s will be even more fulfilling than the 1920s.

Better a square foot of New York than all the rest of the world in a lumpbetter a lamppost on Broadway than the brightest star in the sky.

Texas Guinan

PREFACE

Ive long been fascinated by periods of social disruption and how they help refashion American society. I came of age during the tumultuous 1960s and was part of the radical struggles that challengedand changedU.S. political policy and social life. It was a period of contestation, a transformative historical era. We may be on the verge of a comparable moment today.

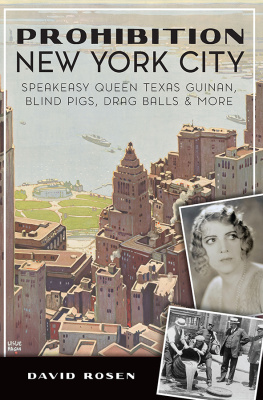

Prohibition New York steps back a century from today to illuminate a remarkable different moment of Gothams social dislocationlife during the Roaring Twenties. It continues the investigations I began with Sex Scandal America: Politics, Morality & the Ritual of Public Shaming (2009) and followed with Sex, Sin & Subversion: How What Was Taboo in 1950s New Yorks Became Americas New Normal (2016).

This book is neither a biography of Texas Guinan nor a history of Prohibition in New York. Rather, it uses her story as a keyhole into some of the secrets of Prohibition-era city life. Guinan (18841933) was a Broadway showgirl and early silent film star who, by chance, ended up running some of the citys grandest speakeasies. Her life illuminates a unique moment of social disruption in Gotham and throughout the nation. Without appreciating the illicit underworld that Texas symbolized, one cant fully grasp the roar of 1920s New York.

Texas, her speakeasies, the gangsters who backed her and the innumerable customers who patronized her clubswhom she affectionately referred to as suckerscontested conservative moral authority. They, along with millions of Americans who went to local speaks throughout the country, challenged the power of the federal governmentand conservative Christian forcesthat imposed abstinence as the law of the land. These activists voiced the inebriated pleasures of drinking, nightlife socializing, jazz, interracial mixing, dancing, gay cruising, gambling and illegal drugs as well as what might happen later in the evening, including engagements at rent parties or sex circuses, encounters at drag balls, hookups with hookers and rendezvous at bathhouses. Collectively, they contributed to the repeal of Prohibition.

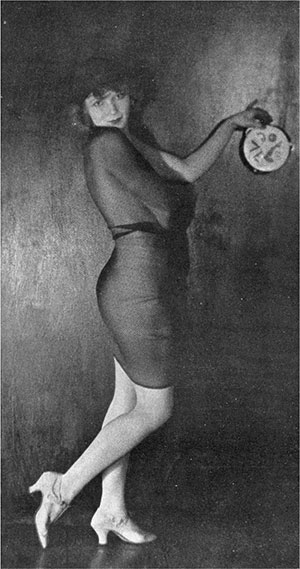

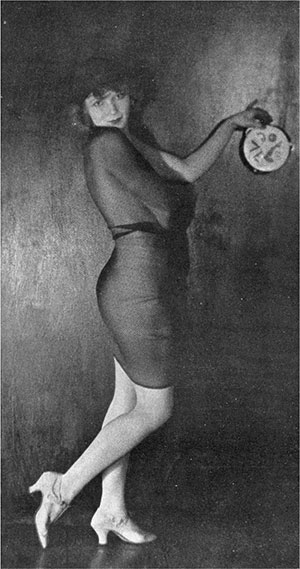

Texas Guinan, 1920. Wikimedia Commons.

Prohibition went into effect on January 17, 1920, and was repealed on December 5, 1933, one month after Guinan died on a road trip in Vancouver on November 5, 1933. However, four years after the repeal of Prohibition, the federal government imposed prohibitions against the distribution, sale and consumption of marijuana. Federal authorities classified marijuana as a Title 1 drug, and this classification is still in place, although millions of Americans violate the existing laws and an increasing number of states across country have legalized marijuana for medical and recreational uses.

A century ago, Woodrow Wilson vetoed the National Prohibition Act, but a conservative Congress quickly overrode his veto and imposed abstinence for the next thirteen years. With Donald Trump as president and the 2020 election approaching, one can only wonder if a new era of Prohibition might be in store for America.

I would like to extend my personal thanks to a group of friends who helped me with this labor of love: Madeline Belkin, Chris Carlsson, Peter Hamilton, Inge King, Laura May, Linda Mochler, Donald Nicholson-Smith, Randolph Reynolds, Lianne Richie, John Galbreath Simmons and John Trinkl. And a special thanks to Inge for her patience educating me about picture editing and Lianne for her computer knowhow.

Finally, I would like to thank The History Pressand especially Banks Smitherfor their support publishing this book, a work long in gestation.

Introduction

THE LURE OF TRANSGRESSION

WHAT IS ACCEPTABLE?

January 15, 1920, was a cold night in Gotham, just six degrees Fahrenheit, but New Yorkers gathered in nightclubs, saloons, bars and local watering holes throughout the city to engage in an old-fashion wake, to enjoy one last drink and, collectively, bemoan the coming imposition of Prohibition. And drink they did.

They gathered on the Lower East Side at Maxs Little Hungary on Houston Street and in midtown at Maxims de Paris at Madison and 61st Street. In the heart of Times Square, they mingled at the Majestic, the Caf de Paris, Jacks on 6th Avenue, Joels at West 41st Street and 6th Avenue and at Lambs on 42nd Street.

At Rectors, a legendary lobster palace located at Broadway and 44th Street, five hundred mourners raised their glasses in rousing revelry. At the throngs center stood Gilda Gray, the Ziegfeld Follies dancer famous for her scandalous shimmy. Tonight she was costumed as a handmaiden to Bacchus, the Roman version of Dionysus, the god of the grape harvest and joyous intoxication. The scantily clad Gray, poised before an effigy of the god, led a parade line through the assembled crowd. The guests, pushing and shoving, tore at the deity until little was left and its remains were finally placed in a coffin and taken from the room. New York and the nation would never be the same.

People have been drinking alcohol in Gotham since before the city was settled. An apocryphal story from old claims that Henry Hudson served gin to a party of Lenape Indians in 1608 on what is todays Manhattan Island. According to this legend, the Indians passed out, to a man. The often-forgotten part of the story is that the Lenape named the place Manahachtanienkthe island where we all became intoxicated.

Beer, cider, gin, rum and other intoxicating beverages were not only safer in early America, an era without potable water, but far more pleasurable than water or nonfermented fruit drinks. Benjamin Rush, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence and a representative to the Continental Congress, was one of the nations leading early physicians. He believed that excessive alcohol consumption negatively affected both physical and psychological well-being. His belief was a truism of American medicine for two centuries, profoundly influencing moral beliefs and legitimizing the temperance movement.

Gilda Gray. Wikimedia Commons.

Next page