ABOUT THE AUTHOR

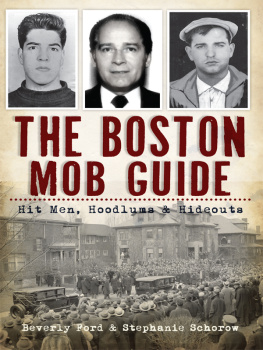

STEPHANIE SCHOROW is the author of seven books on Boston history, including Drinking Boston: A History of the City and Its Spirits, The Cocoanut Grove Fire, Boston on Fire, East of Boston: Notes from the Harbor Islands, and The Crime of the Century: How the Brinks Robbers Stole Millions and the Hearts of Boston. She co-wrote The Boston Mob Guide: Hit Men, Hoodlums & Hideouts with Beverly Ford. She has worked as an editor and reporter for the Boston Herald, the Associated Press, and numerous other publications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A book such as this would not be possible without assistance, advice, and encouragement from a huge number of peoplea few of whom asked to remain anonymous. I am eternally grateful to the many researchers, retired officials, academics, journalists, former musicians, and library staffers who patiently answered my inquiries as well as the many folks who responded to my questions posted on Facebook.

I am especially thankful to Jessica Berson, Jan Brogan, and David Kruh for sharing their research. I want to very much thank for their time and insights: Paul McCann, Regina Quinlan, Mark Pasquale, John Sloan, Barney Frank, Mr. and Mrs. Ray Flynn, Kevin Fitzgerald, Thomas Dwyer, George Mansour, Diane Modica, Lauri Umansky, Julie Jordan, Steve Nichols, Elizabeth Brawner, Jonathan Tudan, Joel Feingold, Lisa Treat, Heidi Pangratis, Peter Chan, Uncle Frank Chin and his sister Amy, Angel Walker, Howard Yezerski, Peter Bates, and others who asked not to be named. Very special gratitude goes to law enforcement experts Billy Dwyer and Ed McNelley for sharing their recollections. Very deep thanks go to Danny Puopolo and Francesca Sciaba for reliving a nightmare for me. I sincerely thank Marta Crilly, Margaret Sullivan, Rosemarie Sansone, Don Stradley, Tom Palmer, Stephen Kurkjian, Judy Rakowsky, Martha Stone, Mark Krone, Nathaniel Sheidley, Lisa Tuite, Renee DeKona, Susan Chinsen, David Bernstein, and Carol Rosenberg for their assistance, stories, referrals, suggestions, and support. Kathy Kottaridis and the staff of Historic Boston must be acknowledged for giving me a tour of the Hayden Building and regaling me with stories about its rehabilitation.

Everlasting gratitude goes to Arthur Pollock, Boston Herald photographer extraordinaire, for his service, encouragement, and stories. (Also for the bagels). A shout-out to Donna Halper for finding a key article for me, and to David Waller for rescuing the Naked i marquee. I am extremely appreciative of Thomas Chen for sending me his insightful and thorough dissertation on Chinatown. Thanks to Adam Gaffin for all his work on Universal Hub and the staff of The History Project and the Northeastern University Archives, and to Aaron Schmidt of the Boston Public Library. Thanks to Frank Bellotti, Mike Ingeme, Brother Ralph, John J. Spurr Jr., Doug Meyer, and Judy Farrar.

I dont know what I would have done without my first editor and toughest critic, Florence Schorow. I must also thank my Medford writers group for enduring numerous drafts of this manuscript, Anne Stuart for reading a first draft, and the ROMEOs for sharing their memories. A huge thank you to Caitlin Dow for her editing and Shelby Larsson for her support. Words are inadequate to express my gratitude to Union Park Press Publisher Nicole Vecchiotti for suggesting this topic and supporting me through the books long birth.

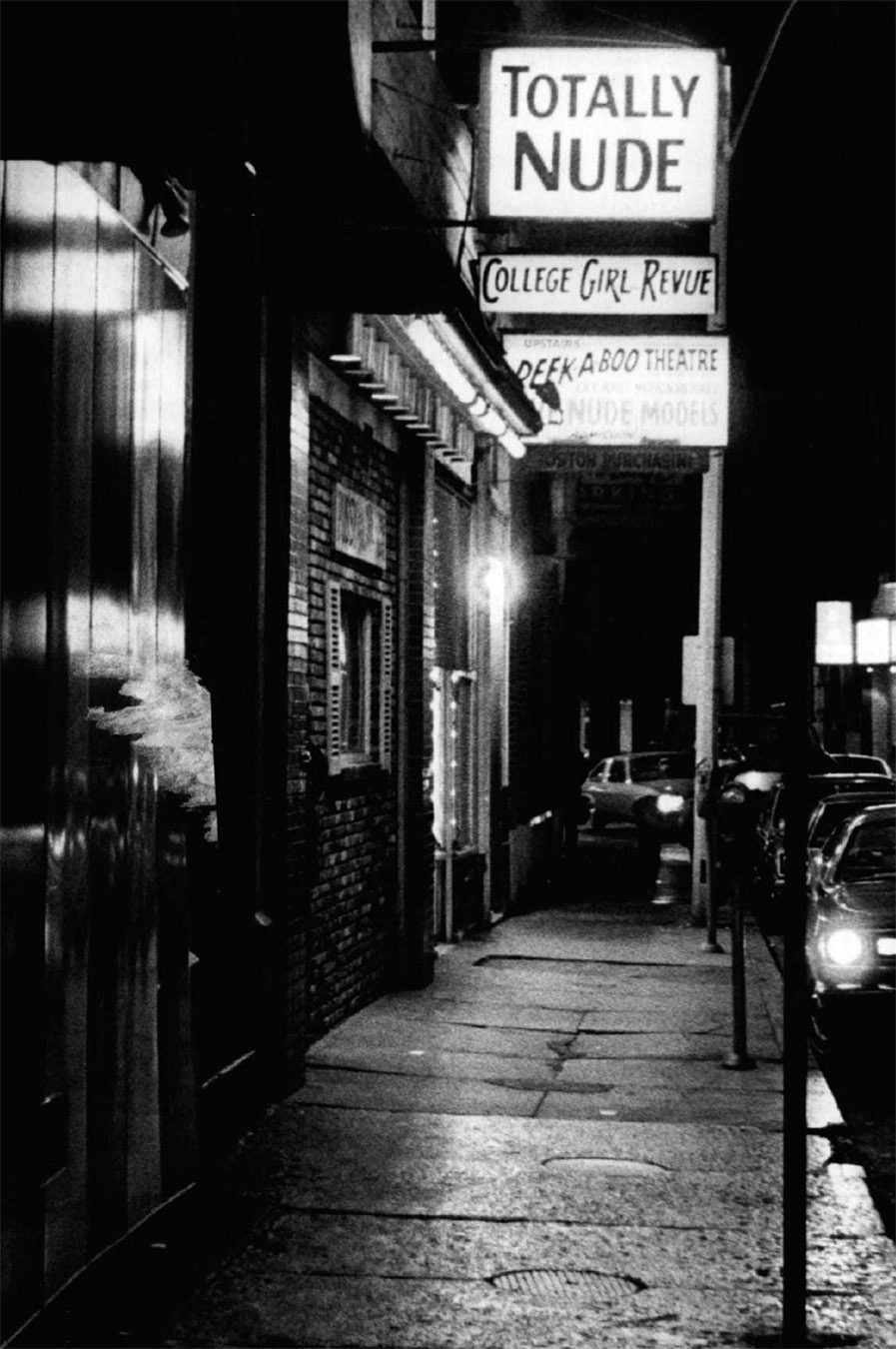

Courtesy Boston Herald.

CHAPTER 1

IT REALLY IS A COMBAT ZONE

1950 to 1960

The barroom and bucket-of-blood days have nothing on that street today.

MUNICIPAL COURT JUDGE GEORGE W. ROBERTS, 1951

O n April 27, 1951, a short article in the Boston Traveler described how one Albert A. Silva, a former United States Navy sailor from East Dedham, was sentenced to a month in jail for assault and battery of a policeman. It was a modest punishment, and Silva got the worst of it; the assailed officer had shot him in the chest. Silva probably didnt feel a thing. By his own account, he had downed a dozen or so drinks at the Playland Caf, a bar on Essex Street, just a couple of blocks from the site of the former Liberty Tree.

Judge George W. Roberts was not amused. Much of the trouble is due to the licensees on this street who would continue selling liquor to a man as they did to this man, he declared. It is a dangerous area and the services should put it out of bounds. This is not the first shooting down there. A sailor actually on duty there was killed. It is really a combat zone.

No one knows exactly how the area of downtown Boston near the intersection of lower Washington and Essex Streetsthe place where the American Revolution begancame to be called the Combat Zone. Likely the name was linked to the proliferation of military police, out to keep an eye on the sailors from the Charlestown Navy Yard or soldiers from the South Boston Army Base as they sought the pleasures of drinks and dames in the seedy bars. The nights often ended in barroom brawls. The drunk and disorderly were hauled off in wagons stationed in the area while the more sober were sent back to base.

Yet up until the 1950s, Washington Streetfrom the point where Kneeland became Stuart Street to the intersection of Winter and Summer Streets (the spot later dubbed Downtown Crossing)was the citys main entertainment district, filled with theaters, shops, offices, and restaurants. By the 1920s, fifteen theaters in the area offered everything from serious drama to vaudeville to travelogues. If Bostonians werent going to a show, they were shopping: the area became the citys retail hub, anchored by department stores like Jordan Marsh, Gilchrists, Raymonds, and Filenes, with its vaunted discount basement.

A South Boston boy who would grow up to be the citys mayor loved walking down Washington Street with his cousin Charliea lead saxophone player for Louis Prima, Gene Krupa, and other popular big band leadersto see a show in one of the theaters. The admission price included a movie screening and a live band performance. His cousin would take him backstage to meet the musicians, a treat for any star-struck kid. Some years later, he and his wife would dine at what he thought were the finest restaurants in Boston: Luigis on Essex Street, the Prince Spaghetti House on Avery, or Jacob Wirth, the popular German pub on Stuart. Those memories were seared into the mind of Raymond Flynn, who served as Bostons mayor from 1984 to 1993, even after everything that followed.

Boston has been described as a city of neighborhoods. Beacon Hill, Back Bay, Dorchester, South Boston, the South End, and the North End each have their own character, quirks, and loyalties. But downtown Boston was notuntil well into the 2010sgenerally viewed as a neighborhood despite its thriving community of Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans during the nineteenth century.

The Chinese community and other immigrant groups settled in the South Cove, an area created in the 1830s with landfill piled into Boston Harbor. It included both housing and a railroad terminal. Beginning in the 1870s, Chinese immigrants, many coming from the American West, moved into this housing. Some opened businesses, such as laundries and restaurants, while many Chinese women worked in the nearby garment factories. Fashionable town-houses dotted Harrison Avenue, but an elevated train track (which was used from 1900 to 1942) and an expanding number of garment factories made the area less desirable to well-heeled residents. From 1940 to 1950, the Chinatown population more than doubled from about 1,383 to roughly 2,900.