One

THE OLD SOUTH END

In the early 19th century, the South End of Boston was a fashionable residential district with impressive mansions, tree-lined streets, and lavish gardens. The streets such as Summer, Franklin, Otis, High, and Pearl Streets were lined with imposing brick mansions, many of which were designed by Bostons gentleman architect and native-born son Charles Bulfinch (17631848). Beginning in the 1790s, the Harvard Collegeeducated Bulfinch, following a grand tour of Europe, began transforming the town of Boston from a small, provincial seaport to an urbane and sophisticated city of brick and granite buildings. Starting in 1793 with the design and construction of the Tontine Crescent on Franklin Street, Bostons architectural outlook was to be vastly broadened by Bulfinchs astute perspective and obviously perceptive neoclassical designs. He was to serve as chairman of the selectmen of Boston and oversee the implementation of new architectural perspectives and how they ultimately changed the face of the old town. Between 1793 and 1820, he would lay the underpinnings of what would become the city of Boston in 1822 and the gateway to 19th-century architectural, topographical, and ethnic changes that would radically transform Boston into the Athens of America and, as it was later coined by Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Hub of the Universe. In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Old South End had become the most fashionable residential area in town with close proximity to the waterfront and breathtaking views of the harbor from Fort Hill, a one-time fortified eminence.

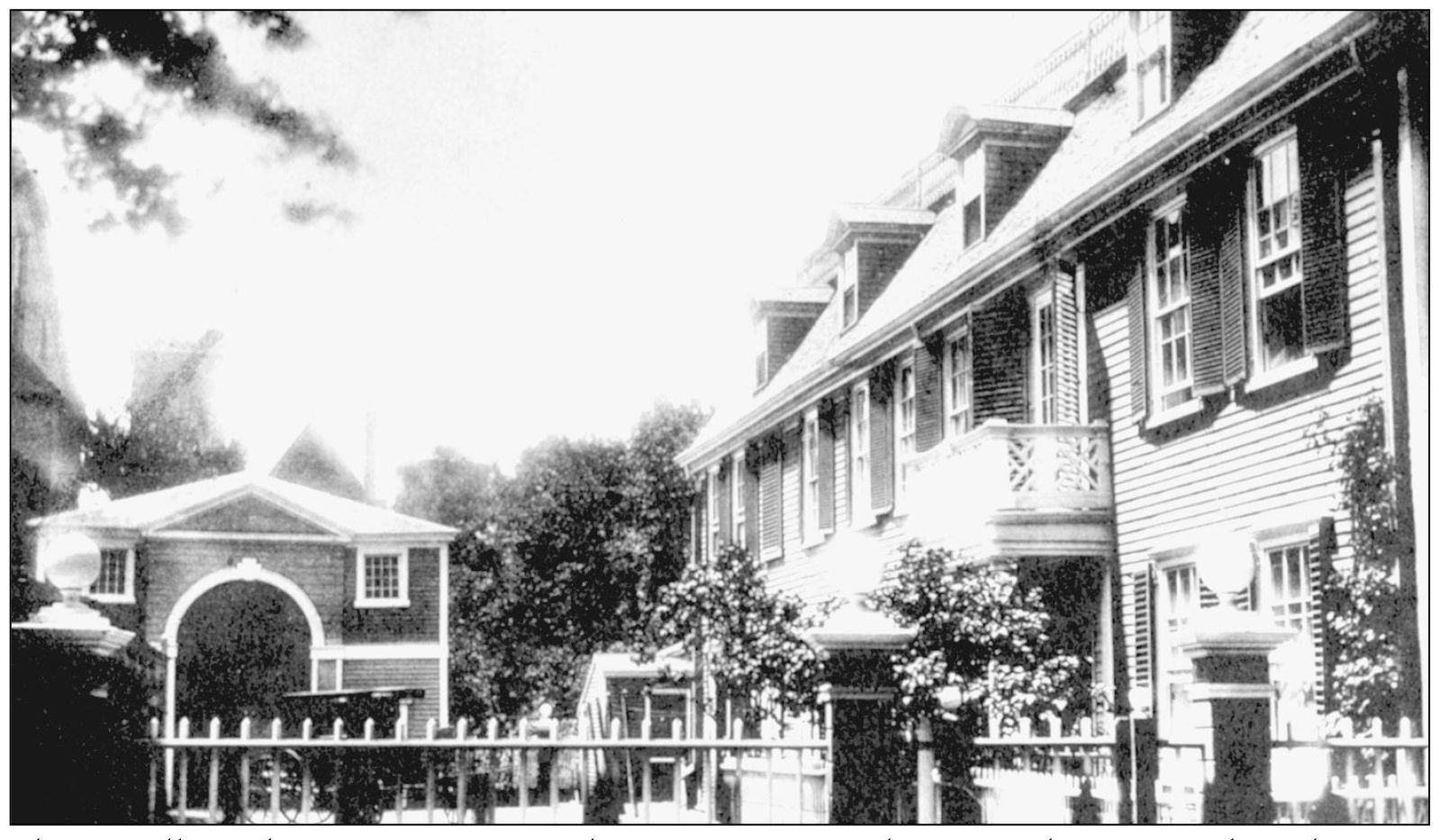

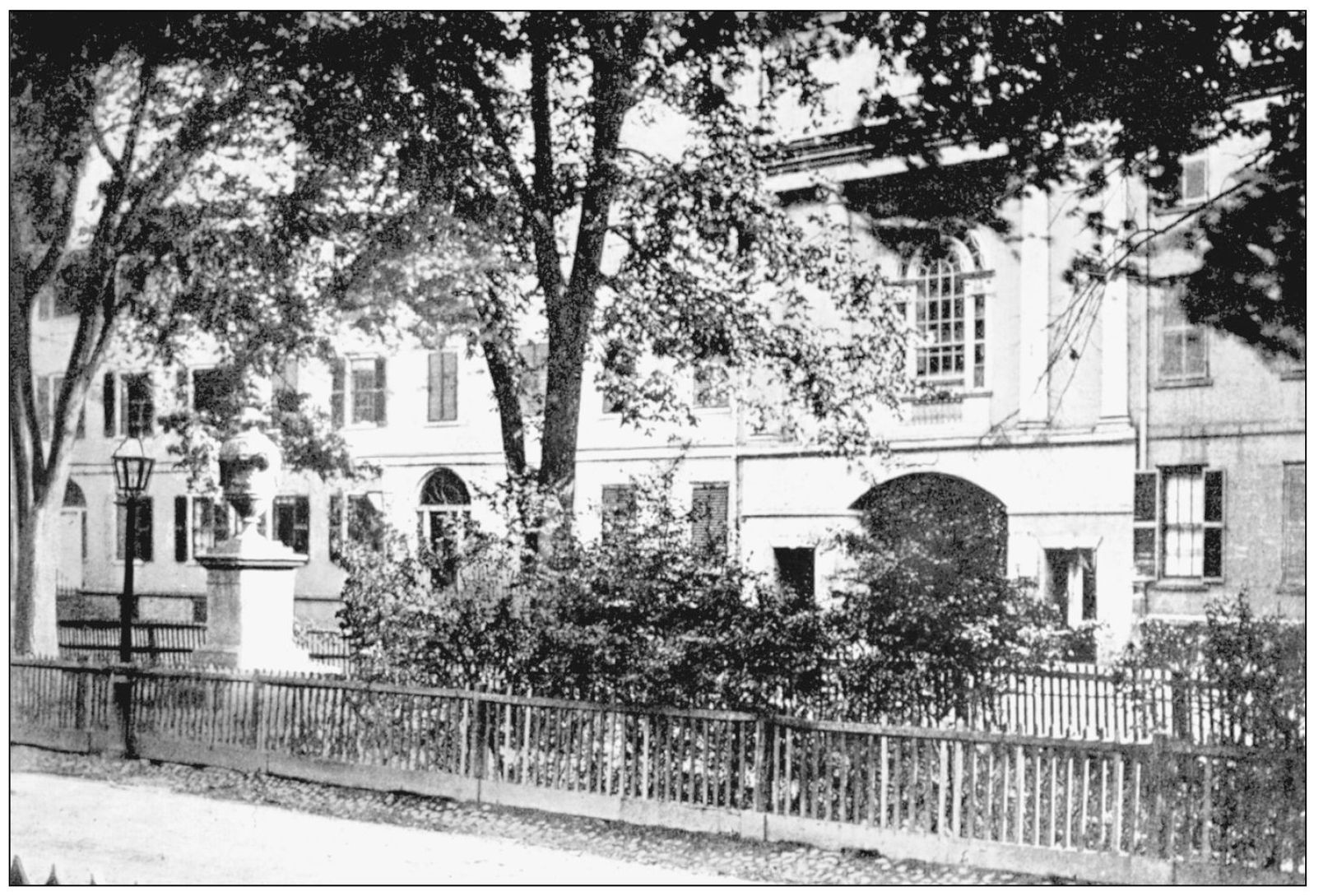

The Vassall-Gardner House once stood on Summer Street between Chauncey and Washington Streets. Built in 1727, it was typical of early-18th-century wood houses in Boston that were set in a fenced, well-kept garden. The house is seen here just prior to its demolition in 1854 to make way for a commercial block built by the Gardner family. The still well-tended Colonial house had a large carriage house set at the end of a cobblestone drive. The crenellated tower seen in the distance is that of the Church of Our Savior (organized in 1845 ), which was designed by J.H. Hammatt Billings and built on Bedford Street. The house was a poignant reminder of the once common pre-Revolutionary streetscapes in town, and it would remain a remarkably long time into the 19th century. Today, Macys occupies its site.

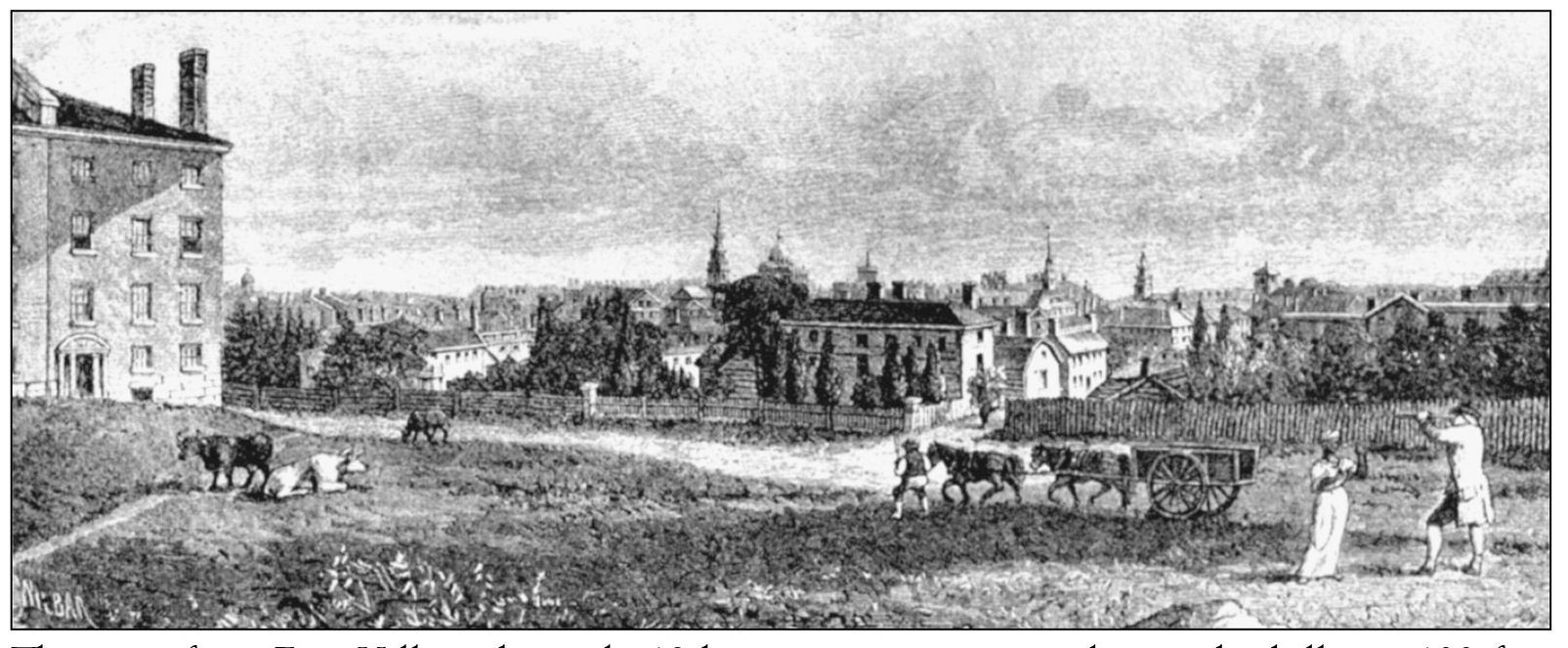

The view from Fort Hill in the early 19th century was spectacular, as the hill was 100 feet high. Accessible from Milk, Broad, and, High Streets, the area was developed with a circle of respectable mansions facing a circular green that was enclosed by a cast-iron fence. Although a secluded neighborhood, it attracted numerous residents who often wandered to the crest of the hill in the early summer evenings to enjoy the views and cool breezes. In this print, a corner of a rowhouse can be seen on the left, with cows grazing on the green and a man looking through a telescope on the right. The town lies in the distance, and the Park Street Church, the Old State House, the Old South Meeting House, and the Old North Church can be seen rising above the houses and shops.

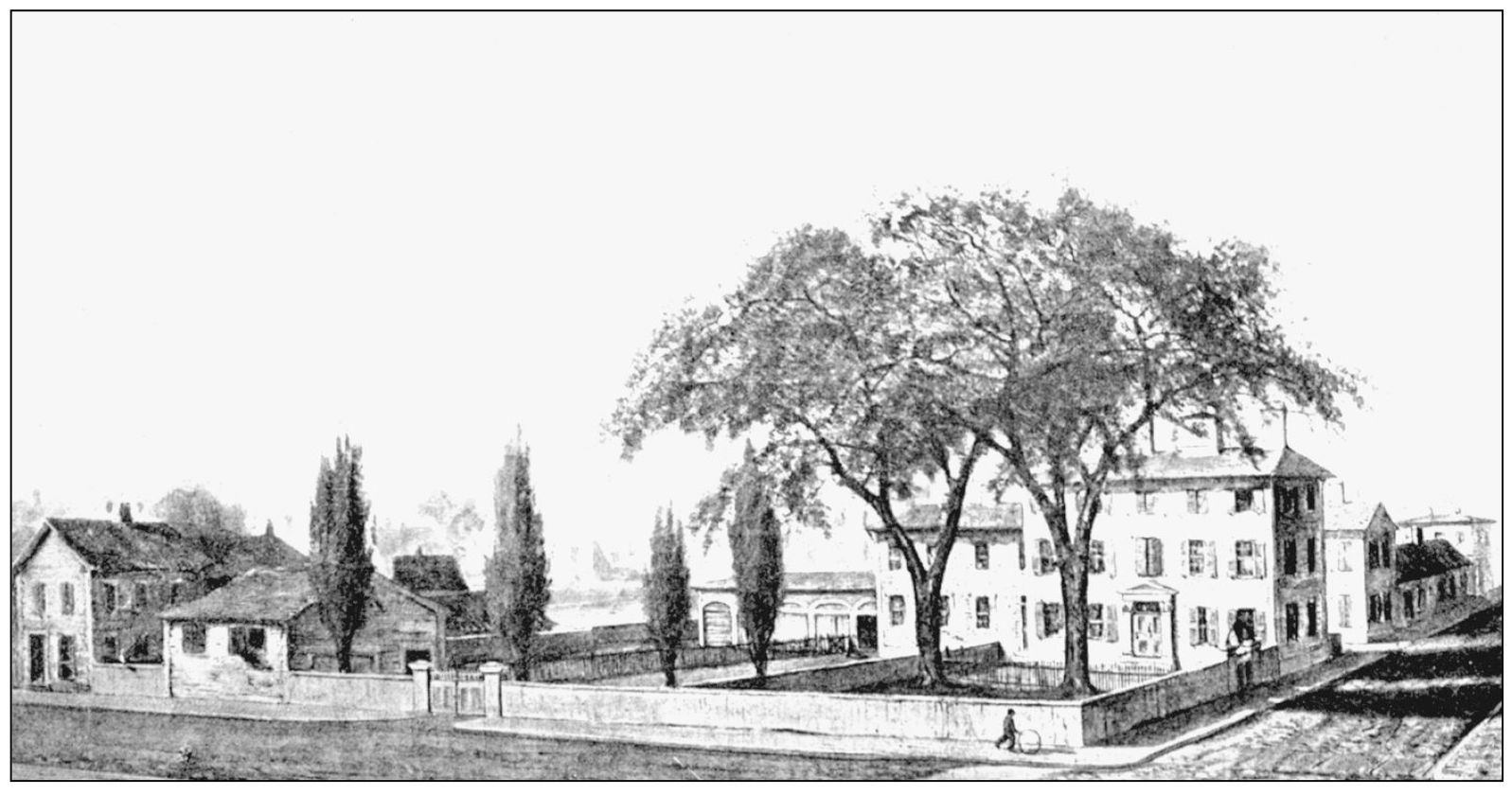

The Dalton House was set in a large garden at the corner of Congress and Water Streets. Built in 1758 by Capt. Timothy Dalton, the three-story house was typical of houses in the Old South End in the 18th century. Congress Street, today a major street in the financial district, was a combination of Atkinson and Dalton Streets and was renamed in 1854.

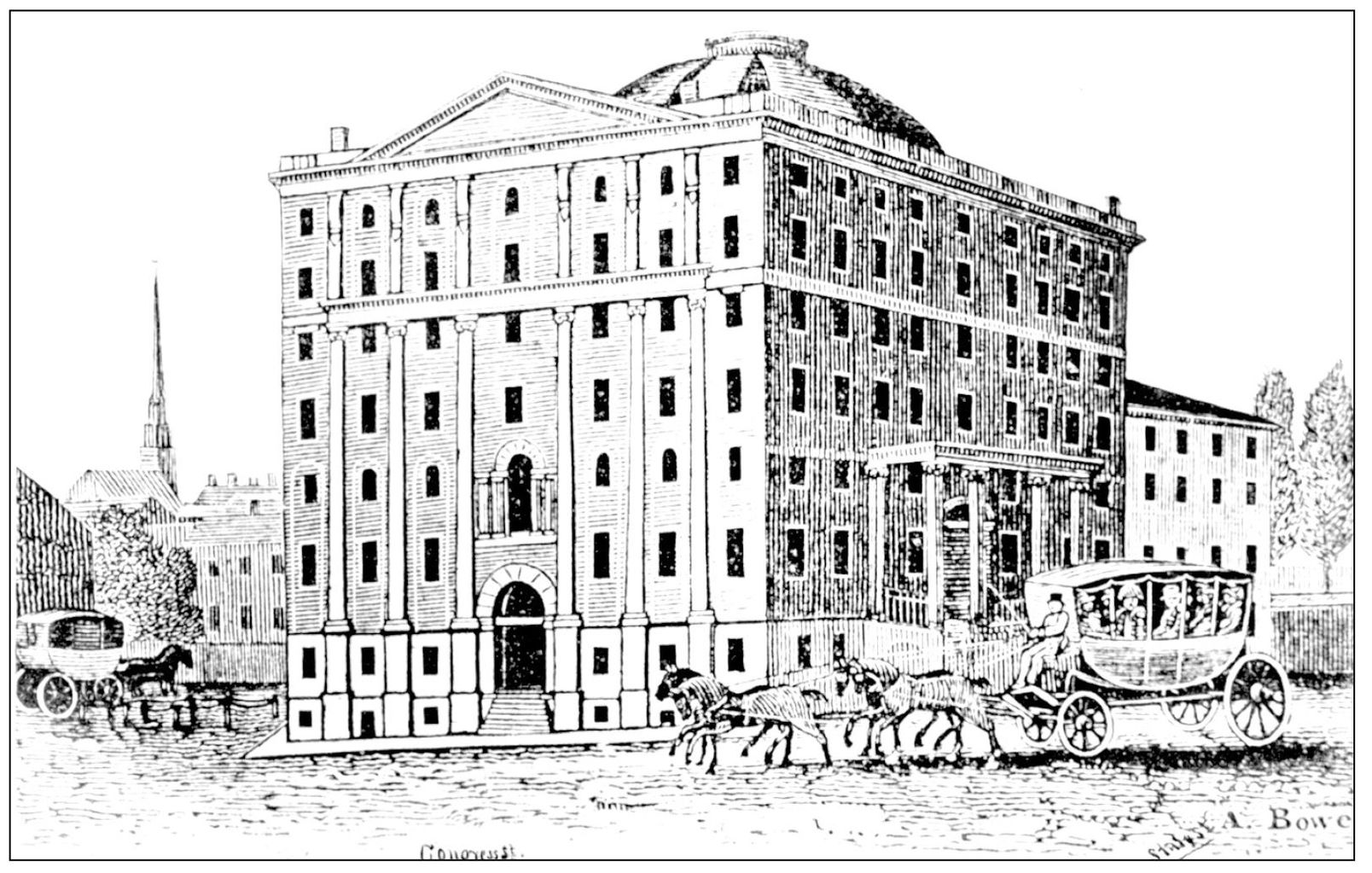

Upon its completion in 1808, the Boston Exchange Coffee House was probably the most impressive building ever built in Boston. Seen here in a woodcut by Abel Bowen, it was built at the corner of Congress and State Streets, facing Congress Square. The building was seven stories in height with a center dome and cost a mind-boggling $500,000. It was the leading hotel in town, with a reading room, a drawing room, and a dining room that could seat 300 diners. In 1817, accommodations for the 11 Masonic bodies in Boston were provided here, and their lodges were elegantly furnished. However, all of this elegance was destroyed in a fire in 1818. On the far left can be seen the spire of the Old South Meeting House.

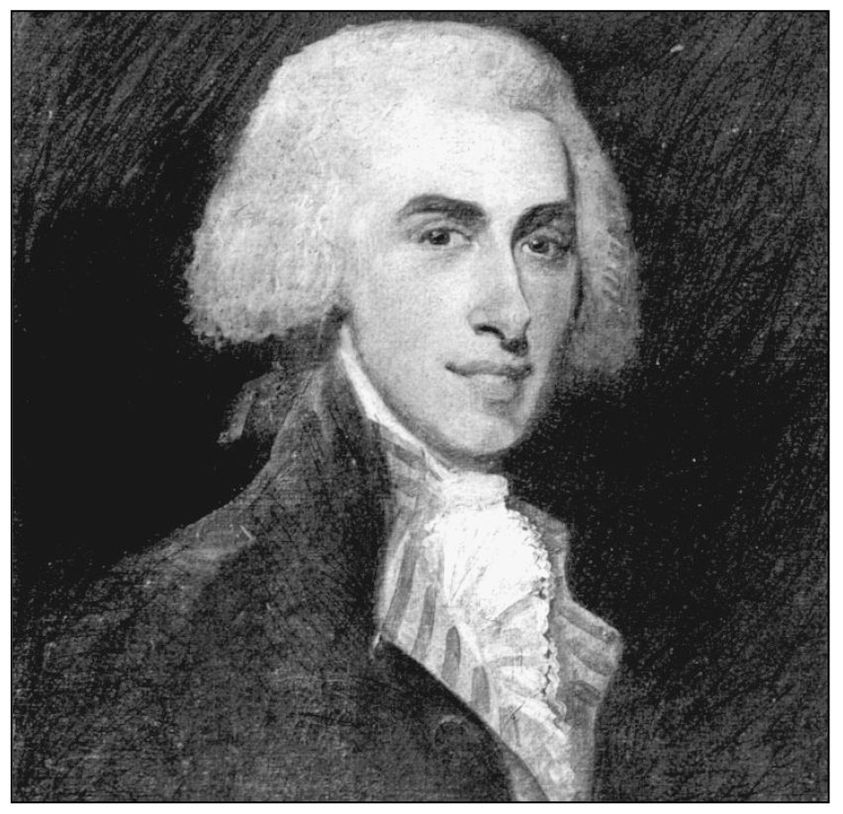

Scion of the prominent Apthorp and Bulfinch families, Charles Bulfinch was destined for the life of a gentleman. However, his projected Franklin Street development, known as the Tontine Crescent, forced him into bankruptcy and the need to view architecture as a remunerative career. Although unfortunate for Bulfinch, this change in thinking was Bostons immense gain. He was not an architect in the modern sense, he was an artist and had mastered some of the principles of his calling. Bulfinch served as a selectman of Boston between 1789 and 1793, serving as chairman from 1797 to 1818, in addition to being the chief of police.

The Tontine Crescent was a 240-foot row of houses designed by Charles Bulfinch and built between 1791 and 1795 as the first connected houses in Boston. Built of brick, the rowhouses shared a uniform setback from the street and roofline. The facades were painted grey to emulate Portland stone with white trim. The second floor of the central pavilion held the headquarters of the Boston Library Society, while the third floor housed the Massachusetts Historical Society. The locations were convenient, as many of the neighborhood residents patronized both. In the center of the 300-foot-long elliptical green was a large stone urn surmounting a plinth base that Bulfinch had brought back from England and placed there in memory of Benjamin Franklin (17061790), for whom the street had been named. After 1858, when the area was rebuilt with granite commercial buildings, the urn was placed on the Bulfinch family lot at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.