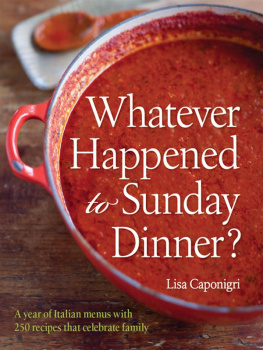

For Nonna Anna Cerullo Galasso, Nonna Maria Assunta Ferro Saporito, and my mother, Louisa Florence Galasso Saporito. Three wise women whose reverence for the foods of Italy lives on in these pages.

contents

You may have the universe if I may have Italy.

G IUSEPPE V ERDIS Attila

introduction

Everything I know about the traditions of real Italian cooking came not from any stint in culinary school but from three wise, clever, and strong-minded women with humble beginnings: my two southern Italian grandmothers (nonnas), Maria Assunta Saporito, born in Caltanissetta, Sicily, and Anna Cerullo Galasso, born in the little town of Bellizzi, near Naples, and my mother, Louise Florence Saporito, who was a second generation Italian American and the only one of the three who had a formal education. You could say that they lived by their wits and common sense and that was what made them wise. They have all passed on and even though there is no one left in my family to talk to about all the foods that I grew up with and that forever identify me as Italian American, I am left with a deep and persistent need to carry on where they left off.

Each of these women found a way to make cooking a profession. This was, of course, in addition to what was expected of them as housewives of their generation. Nonna Saporito, tall, feisty, and opinionated, became a butcher and had her own butcher shop in Fairport, New York. As a girl, I would spend my school vacations with her, helping her with customer orders. I still have her handmade cleaver with the chestnut wooden handle that she wielded with the grace of a symphony conductor and the force of an ace baseball pitcher when she was cutting meat and chicken.

Nonna Galasso, short, spiritual, and deliberate, ran a boarding house after my grandfather Carmen, a tailor, was tragically killed in an accident. Left with eight children, she cooked her way to prosperity, such as it was. Having the only bathtub in town, she offered patrons a meal and a bath for twenty-five cents. People stood in line outside her door for hours.

My mother, petite, determined, outspoken, generous to a fault, and with fire-red hair, had all the pressing household duties of most women of her generation as well as providing for my father, seven children, and Nonna Galasso, for whom she became the sole caregiver. In her mid-fifties she decided to become a dietician, validating her goal of becoming someone who had a career outside the home.

Growing up in a small town in western New York, it was difficult not to be drawn into a solely southern Italian lifestyle surrounded not only by family members speaking in Neapolitan dialect but also by many of their friends from the old country who lived nearby in a clustered Little Italy where the air was permeated with the smells of simmering tomato sauce and homemade bread. Nonna Galassos friends spent hours in our kitchen discussing the merits of everything from boiling cardoons to where to buy the best squid. So determined were they to hang on to their traditions that no trek was too great for finding such things as the best fresh eggs, even if it meant walking a mile to purchase them from the chicken man so that they could make maccarun (macaroni).

Looking back, my favorite day of the week was Sunday because the preparations for dinner started early Saturday morning with bread being made by my mother at her thick maple butcher-block baking center that commanded almost battleship space in the kitchen. Along with bread she would make something sweet for Sunday morning breakfast like fluffy cinnamon rolls, dense with raisins, lots of cinnamon, and the silkiest and most luscious-tasting lemon confectioners glaze that gave them a truly professional pastry shop look. And she wouldnt stop there because a towering, airy sponge cake was a must for Sunday dessert. The smells coming from that kitchen were so good, they were almost hypnotic, and the anticipation would build all day Saturday for Sundays meal. Memories like these have stayed with me my whole life and many of them have been preserved in the eleven cookbooks that I have written over the course of twenty years on the subject of regional Italian food. So what is left to say? Plenty.

I like to think of this book as a continuing journey into the world of Italian cooking and culinary traditions, past, present, and future. Past because it contains many favorite recipes from home that I want to pass on not only to my family but also to anyone who is passionate about good homemade food. Present because after more than twenty years as the host of Ciao Italia on PBS, it has been my goal to keep our loyal viewers informed about changing food trends and how classic Italian ingredients are being adapted for use in todays kitchen. Truthfully, I am both a traditionalist and a minimalist when it comes to cooking. I like the best ingredients to shine on their own, and I am very much against any adulteration or tinkering with any of Italys core products. Future because as I continue my culinary travels through the regions of Italy, armed with the knowledge my nonnas and mother instilled in me, I have felt right at home cooking in Italian kitchens alongside many chefs and home cooks, who like me want to preserve the essence of Italian home cooking, which is and always will be the quality and integrity of the ingredients simply prepared by the gentle hands of a cook in tune with seasonal foods. That message became the motto of the Slow Food movement that started in Bra in 1986 in the Piedmont region and is now spreading worldwide. I continue to learn that food trends will always come and go, but the crux of what constitutes Italian food is forever rooted in the traditions of the past.

And the past can teach us much about the future of our food supply. When I travel the back roads of Italy with its gorgeous vistas of vineyards, vegetable gardens, and fruit orchards, I hope that this form of artisan farming will survive in a world where many family-run farms are disappearing not only in Italy but here as well. And as I get older, I am grateful that I was exposed at an early age to home gardening at the backdoor so to speak, where Nonna Galasso had her little patch of mint, beans, and tomatoes.

Home cooking is disappearing, too, at an even faster pace as busy lives dictated by relentless schedules swallow us up like a vast black hole. Fears about nutrition have gripped our attention with concerns about the safety of the foods we consume, where they come from, and the pesticides and chemicals they have been exposed to. These are legitimate worries and a great argument for becoming informed about our food supply, getting back into the kitchen, and bringing families back to the table.

In my grandmothers day putting a meal on the table was arduous work because everything was done from scratch. No immersion blenders, food processors, or bread machines speeded the process. And yet today with all the cooking gadgets at our disposal, and the myriad of choices in the supermarket, making a meal seems for many of us too time-consuming, too daunting, and just too bothersome.

How do we bring back family meals? First we must realize the importance of eating together. This is a quintessentially Italian concept. Its not primarily about the food, its what the food can lead us toconversation, togetherness, reassurance, and relaxation. Anyone who has ever shared a meal in an Italian home can attest to long happy hours at the table. Second we need to teach children about good food, where it comes from, and how to make healthy choices that will continue into their adult lives. That means taking the time to involve them in the cooking process. I have to say that as a kid, I hated being in the kitchen trimming beans, making pasta, and washing dishes, but all those chores connected me in an intimate way not only to the food but also to the people who prepared it, and it led me to where I am today. Third, and this is a tough one, we need to try to have as many meals as possible together. Even if you can only have one or two sit-down meals during the week, it is a start.