Copyright 2013 by Salinas Press, Berkeley, California.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, Salinas Press, 918 Parker St, Suite A-12, Berkeley, CA 94710.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering medical, legal, or other professional advice or services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. The fact that an individual, organization, or website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the individual, organization, or website may provide or recommendations they/it may make. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read.

For general information on our other products and services or to obtain technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (866) 744-2665, or outside the United States at (510) 253-0500.

Salinas Press publishes its books in a variety of electronic and print formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books, and vice versa.

TRADEMARKS: Salinas Press and the Salinas Press logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Arcas Publishing, and/or its affiliates, in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Salinas Press is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

ISBN: 978-1-62315-264-2 (paperback) / 978-1-62315-303-8 (e-book)

Introduction

B elieve it or not, theres no such thing as Italian food. In fact, the cuisine of Italy is a mosaic of regional cuisines unique to areas such as Bologna, Milan, Naples, Piedmont, Rome, Sicily, Tuscany, and Venice. For centuries, Italys boot and islands were divided into more than a dozen separate kingdoms, republics, and duchies with their own laws, languages, cultures... and cooking traditions.

It wasnt until 1861 that the Italian Peninsulas numerous states were unified into a single nation, but even now, the food of Italy encompasses the dishes of nearly twenty different, distinctive, regional cuisines. The eggplant, citrus, swordfish, and anchovy dishes of Sicily so influenced by Spanish, Greek, and Arabic flavors have little in common with the Austrian-, Hungarian-, and Croatian-influenced stews and cured meats of Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

Then theres the New World. Many of the ingredients now central in Italian cookerytomatoes, bell peppers, zucchini, beans, cornmeal, and othersdidnt even exist in Europe until the explorers of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries imported them from North and South America. And ever since Italian immigrants began to arrive in the United States in the nineteenth century, theyve created an entirely new cuisine: Italian American. Meatball heroes, chicken parmigiana, and baked ziti are as purely American as pot roast, po boys, and peanut butter. Dishes that originated in Italy, such as pizza and lasagna, have been given such a powerful American twist that theyre in a culinary category all their own.

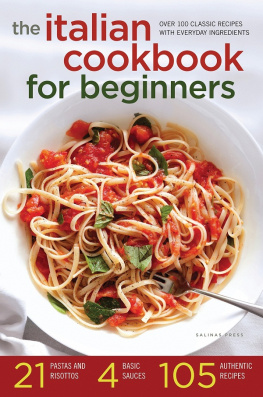

Put it all together, though, and the result is a vibrant mlange of fresh, robust flavors; rich, enticing aromas; intriguing, complementary textures; and gorgeous, exuberant colors. It all melds together into one of Americas favorite cuisines. In all its variety, Italian-inflected cookery draws almost everyone to the table and almost every amateur chef to the kitchen. Yet, this delicious food is surprisingly easy to make! You dont need fancy techniques, hard-to-find ingredients, or specialized tools to create mouthwatering Italian dishes; all you need is a desire to mangia.

Read on and youll find everything you need to know about cooking Italian for yourself, your family, and your friends. Buon appetito!

How to Eat Italian

Italians traditionally considered pranzo (lunch) the main meal of the day. In the afternoons, workplaces and schools would shut down for a few hours, and workers and children would return home to eat. Dining was leisurely and sumptuous, with several courses eaten in succession. Times have changed, though, as the pace of business and the number of working women has rapidly increased. But most shops still shut down from about 1:00 or 1:30 p.m. to 3:30 or 4:00 p.m. for pausa pranzo (lunch break), a throwback to the old days. Today the bounteous meal that once was lunch in Italy has shifted to the evening hours.

A full-on cena (dinner) can consist of as many as seven courses: aperitivo (hors doeuvres), antipasto (appetizer), primo (first course, usually pasta), secondo with contorno (second course, usually fish, poultry, or meat, with vegetables), insalata (salad), formaggi e frutta (cheese and fruit), and dolce (dessert). For the most part, though, the everyday meal in Italy has two or three courses: primo, secondo with contorno, and possibly dolce. Unless youre entertaining guests, youre more likely to eat one, two, or three courses at dinner, perhaps an antipasto or insalata, a main courseeither a pasta or a protein with sidesand dessert. Your salad will come before instead of after the main course; youre unlikely to eat both a pasta dish and a meat dish at the same meal; and you dont think of cheese and fruit as a follow-up to an entre.

Its easy to plug Italian dishes into an American meal plan. As with any dinner, its just a matter of balancing flavors, aligning heartiness, and accounting for nutrition. When you put together a menu the Italian way, harmonizing the courses is considered just as important as balancing the ingredients in a dish. Likewise, when you design a meal that includes lots of courses or multiple dishes per course, follow Italian tradition by planning on smaller servings. Here are a few examples of the kinds of dinner menus you might build from the recipes in this book:

LIGHT WEEKNIGHT MENU

BIG WEEKNIGHT MENU

FESTIVE WEEKEND MENU

FAMILY HOLIDAY MENU

DINNER PARTY MENU

Olive Oil

As youll see from recipe to recipe and chapter to chapter, olio di olivia (olive oil) is the almost universal ingredient in Italian cooking, even appearing in some desserts. Its beautiful flavors are all the more appealing when you remember the health benefits that olive oil offers. But even if it were bad for your health, your taste buds would still find it very, very good. Using the right olive oil for each recipe is key to making every dish the very best it can be. Dont panic! You dont need to run out and buy half a dozen varieties of olive oilunless you want to, of course. All you need is a good-quality cooking oil and a good finishing oil. Where to start?