Table of Contents

The Myth of Private Equity

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2021 Jeffrey Hooke

All rights reserved

EISBN 978-0-231-55282-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hooke, Jeffrey C., author.

Title: The myth of private equity: an inside look at Wall Streets

transformative investments / Jeffrey C. Hooke.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2021] | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004497 (print) | LCCN 2021004498 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780231198820 (hardback) | ISBN 9780231552820 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Private equityUnited States. | FinanceUnited States.

Classification: LCC HG4751 .H66 2021 (print) | LCC HG4751 (ebook) |

DDC 332.6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004497

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004498

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

Cover image: iStockPhoto

Myth: A widely held but false belief or idea

Oxford English Dictionary

Transformative: Causing a major change in something, often in a way that makes it better

Cambridge Dictionary of American English

Finance does not mean speculatingalthough speculation, when it does not degenerate into gambling, has a proper and legitimate place in the scheme of things economic. Finance most emphatically does not mean fleecing the public, nor fattening parasitically off the industry and commerce of the country.

Otto Kahn, High Finance (1915)

Contents

1

A Day in the Life

2

The Private Equity Industry

3

How Does the Private Equity Industry Work?

4

The Poor Investment Results

5

Private Equity and the Holy Grail

6

The High Fees

7

The Customers

8

The Staffs

9

The Enablers

10

The Fellow Travelers

11

In Closing

IT IS A TUESDAY morning in Baltimore. The sun is shining, and the weather is crisp. With a mild breeze, the flags adorning official buildings flutter gently. The citys crowded streets beckon the stream of commuters into the downtown core. At the traffic circle formed by the citys Battle Monument, a striking marble sculpture dedicated to war casualties, a young Caucasian woman walks uneasily between the lines of the cars waiting at the stop light. Disheveled, with a ragged army jacket and stringy blond hair, she asks drivers for spare change. Her gnarled, weather-beaten hands hold a makeshift cardboard sign that reads, Veteran, will work for food.

A block away, at the corner of Baltimore and Calvert Streets is the SunTrust tower, an imposing office building that houses many corporate and government tenants. Occupying the fourteenth floor is the headquarters of the Maryland State Pension Fund, which manages over $50 billion in assets on behalf of several hundred thousand beneficiaries (see ).

FIGURE 1.1 Baltimore skyline

As 9:00 A.M. approaches, pension fund employees traverse the well-appointed marble lobby and flash their ID cards for the guards manning the security desk. A small crowd gathers near the elevators. Conversations, while polite, are short. Most employees endure long commutes and are in no mood to talk. A popular address for pension employees seems to be Towson, a thriving jurisdiction just north of the city.

A Board Meeting

Upstairs, the Maryland state treasurer, Nancy Kopp, gets ready to chair the funds regularly scheduled board of trustees meeting. At seventy-six, Kopp is a petite woman, with an affable personality and a quick smile. Well dressed, her reserved appearance and low-key style do not translate easily into Hollywood central castings image of a financial titan. She is intelligent, having degrees from both Wellesley College and the University of Chicago, and she completed the coursework and preliminary exams for a PhD in political philosophy.

Kopp came to the treasurers office in 2002, following seven termsor twenty-eight yearsas a Maryland state legislator representing Montgomery County, an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C. She was a star in the House of Delegates, because she understood the budget like nobody else, says state attorney general Brian Frosh. This quality provided the impetus for Kopp to get elected by her legislative colleagues to the treasurers post for five consecutive four-year terms.

With a total of forty-six years tenure as an elected official, Kopp is a stalwart supporter of the Democratic Party, which executes an iron control over most facets of Maryland government policy through the partys veto-proof majority in both the lower and upper legislative chambers. Critics say that she is generally well intentioned, but now, after many years, she meanders through the job, making sure Democratic Party officials are happy, while not rocking any boats.

Over her eighteen years in office as treasurer, she supervised a remarkable upsurge in activity at the pension fund. During this time, the number of plan members rose from 320,000 to over 405,000, and assets increased from $27 billion to $54 billion.

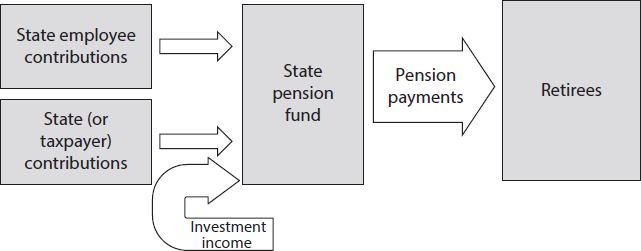

The fund acts as a giant piggybank for state retirees. Current employees contribute a portion of their monthly paycheck to the fund, and taxpayers supplement these amounts with an annual billion-dollar payment. Supplementing these two sources of cash is the funds investment income. From this combined pool of money is deducted the allowances dedicated to retirees. People assume the state guarantees all pensions, but this belief is not enshrined in the statutes, so proper fund management is paramount (see ).

.st0{fill-rule:evenodd;clip-rule:evenodd;fill:#DCDDDE;}.st1{fill:none;stroke:#000000;stroke-width:0.5;stroke-linejoin:round;stroke-miterlimit:10;}.st2{fill-rule:evenodd;clip-rule:evenodd;fill:#FFFFFF;}.st3{fill:none;stroke:#000000;stroke-width:0.5;stroke-miterlimit:8;}.st4{fill:none;stroke:#000000;stroke-width:0.5;stroke-linejoin:round;stroke-miterlimit:8;}

FIGURE 1.2 Maryland state retirement systemillustration of cash flows

Yet the safety of retiree pensions declined over the last two decades, as the system fell from a 95 percent funding ratio at the beginning of Kopps tenure to 72 percent in 2020, indicating a $20 billion shortfall. Eventually, this deficit must be made up in the future, either through increased taxes, higher employee contributions, lower employee benefits, or more investment profits. In fact, the $20 billion deficit exceeded the states regular debt obligations several times over. Thus, in the abstract, the pension funds health is a key concern to state employees and retirees.

Sitting near Kopp is Peter Franchot, the state comptroller and vice chair of the pension fund board. At seventy-two, Franchot is a well-built six-footer. His hair is blond and streaked with grey. A handsome individual, he smiles often, and displays a sunny disposition. Elected to his fourth term as the states chief financial officer in 2016, Franchot looks the part of a solid, stable, professional politician, with a courtly demeanor, ubiquitous blue suit, and red tie.