ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M ANY INDIVIDUALS and organizations have provided support to enable us to write this book. While we are grateful to them all, we single out some of them here to explicitly acknowledge their contributions.

We first want to thank the many managers who so graciously took time out of their busy schedules to talk with us. The best practices that these managers shared with us made an enormous contribution. In particular, we would like to especially acknowledge:

Nada El-Zein, Akzo Nobel

Elisa Scarletta and Mark Stoneburner, Applied Industrial Technologies

Eric Berggren and Stefanie Zucker, Axios Partners

Steve Dehmlow, Composites One

Michael Lanham, Dow Corning

Alice Griffin and Robert Smith, Eastman Chemical

Robb Kristopher and Debra Oler, Grainger

Frank Joop, Intergraph

Joy Chandler and John Stang, Kennametal

Marcel de Nooijer and Eelco van Asch, KLM Cargo

Gene Lowe, Milliken

Bas Beckers and Bert Willemsen, Orange Orca

William Blankemeier, PeopleFlo Manufacturing

Art Helmstetter, Quaker Chemical

Joe Razum, Rockwell Automation (now Baldor)

Siva Mahasandana and Chantana Sukumanont, Siam City Cement

Todd Snelgrove, SKF

Eddie L. Smith, Sonoco

Michael Butkovic and Jackie Eckey, Swagelok

Peeyush Gupta and Anand Sen, Tata Steel

We want to thank the Institute for the Study of Business Markets (ISBM), located at Penn State University, for its financial support of our management practice research. We especially want to acknowledge Ralph Oliva, the executive director of ISBM, and Gary Lilien, the research director of ISBM, for their support of our work.

We also want to express our gratitude to Kirsten Sandberg of Harvard Business School Press for her support and editorial guidance of the project.

James C. Anderson would like to thank his research associates at the Kellogg School of ManagementChaitali Bhagdev, Abhinav Gattani, and Akshaya Gulhatifor their capable assistance in this project. He would also like to thank his assistant, James Ward, for Jamess helpful suggestions and skillful assistance in constructing the figures and tables.

Nirmalya Kumar gratefully acknowledges the following companies and individuals who over the years were kind enough to allow him to test his ideas regarding value in business markets: ACC, Aditya Birla Group (Kumaramanglam Birla, Santrupt Misra), Akzo Nobel, Alcan, Alfred McAlpine, AT&T, Bekaert, Bertelsmann Direct Group (Gerd Bhrig, Ewald Walgenbach), BT (Tim Evans, Gavin Patterson), Caterpillar, Chilton, Continental, Dow Chemical (Carlos Silva Lopes), DuPont, Essel Propack (Ashok Goel), Goodyear, Ambuja Cements, Hewlett-Packard, Holcim (Markus Akermann, Paul Hugentobler), Hydro Aluminum, IBM, ICI, ISS, Jardine Matheson, Jotun, Motorola, Nokia, Norwegian Post, Orkla Group (Karin Aslaksen, Ole Enger), RPG Enterprises (Pradipto Mohaptra), Sabic, Shell, Schindler, Tetra Pak, Volvo, WPP Group (Mark Read), and Zensar Technologies (Ganesh Natarajan). He also thanks his colleagues at London Business School and the associate director of the Aditya Birla India Center, Suseela Yesudian-Storfjell.

James A. Narus thanks the following companies and managers for their assistance with this project: W.R. Grace (Larry Golen), Okuma America (Seth Machlus), Sonoco (Vicki Arthur, Greg Powell), Timken Corporation (Brian Berg), and Volvo Trucks (Clay Flynt).

Developed with the support of the Institute for

the Study of Business Markets at Penn State.

Also by the Authors

JAMES C. ANDERSON AND

JAMES A. NARUS

Business Market Management: Understanding,

Creating, and Delivering Value, 2nd ed.

(Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004).

NIRMALYA KUMAR

Marketing as Strategy: Understanding the CEOs

Agenda for Driving Growth and Innovation

(Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

NIRMALYA KUMAR AND

JAN-BENEDICT E. M. STEENKAMP

Private Label Strategy: How to Meet the Store Brand Challenge

(Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

APPENDIX A

Relating Customer Value and Price

H OW DO CUSTOMER value and price relate to one another? To motivate this discussion, put yourself in the role of a customer manager, and consider the following scenario, which could apply to the acquisition of an electronic component. Then decide which product you would recommend that your firm purchase.

Your firm needs to make a decision about which of two alternative products to purchase: one offered by Supplier M and one offered by Supplier P. Based on two value analyses conducted by your firm, the value for Supplier Ms product is found to be , and the value of Supplier Ps product is found to be 6. The price of Supplier Ms product is I , and the price of Supplier Ps product is .

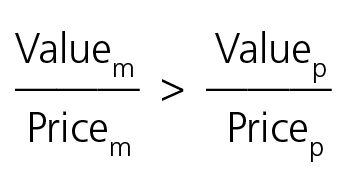

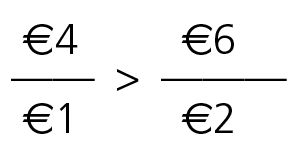

Which suppliers product did you recommend: Ms or Ps? Taking two alternative perspectives would lead to different decisions. Under a ratio comparison, you would recommend Supplier Ms product over Supplier Ps:

Such a ratio comparison has been stated as the way in which customer value and price would be related to one another. As Gerald Smith asserts: This almost always involves two dimensions of value: what the customer gives up (money, time, effort, opportunity cost). Most marketers combine these two dimensions in ratio form: Value = the benefits the customer receives relative to the price paid. Notice the overlooked commensurability issue in Smiths statements as well as his inclusion to our conceptualization.

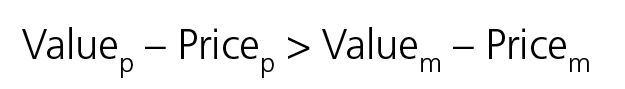

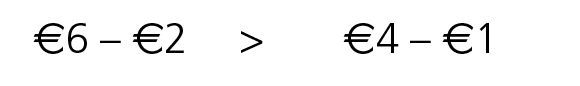

Under a difference comparison, you would make the opposite decision, recommending Supplier Ps product over Supplier Ms:

Although Smith is probably correct that most marketersat least marketing academicsembrace a ratio comparison, this thinking is misguided in two significant respects.

First, qualitative research with customer managers suggests that individuals are much better difference processors than ratio processors. Although we have chosen the monetary amounts in our scenario to facilitate comprehension of the differences between the two kinds of comparisons, division remains a more difficult mathematical operation than subtraction. Pick four numbers a , b, c , and d and try it for yourself, seeing how easy it is for you to divide a by b and c by d versus subtracting b from a and d from c .

Second, and more critical, difference comparisons are the way that businesses keep score on how they are doing. Simply put, they subtract the total cost of doing business from the revenue produced by doing business to determine the profit. While the ratio comparison for the scenario we presented leads to a decision to purchase Supplier Ms product, would a customer firm indeed be better off by purchasing Supplier Ms product versus Supplier Ps product? Consider a situation in which the customer has a purchase requirement of a million units. Even though Supplier Ps product has a higher purchase price than Supplier Ms product (1), this is more than offset by the superior value that Supplier Ps product delivers (2). Thus, a customer firm would have 1 million of incremental profit by purchasing its requirement from Supplier P instead of Supplier M.