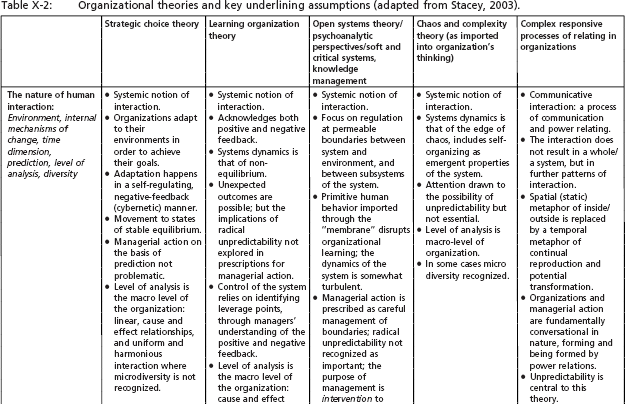

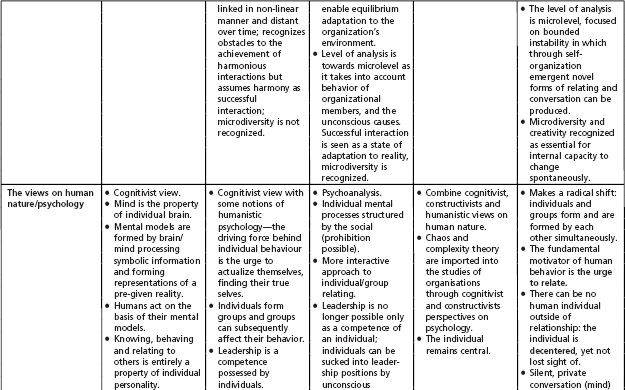

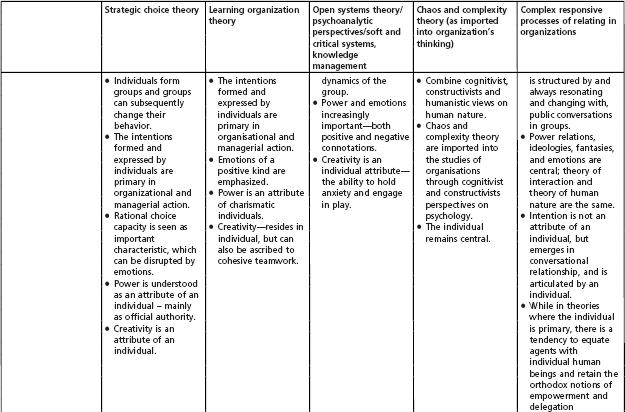

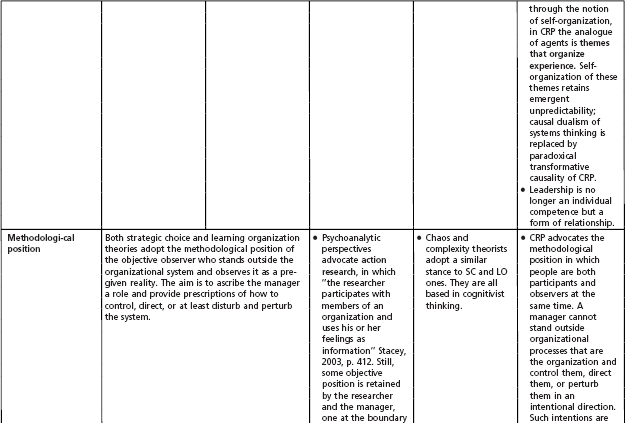

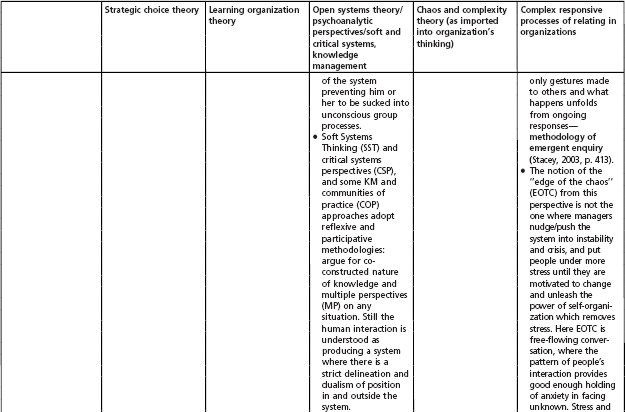

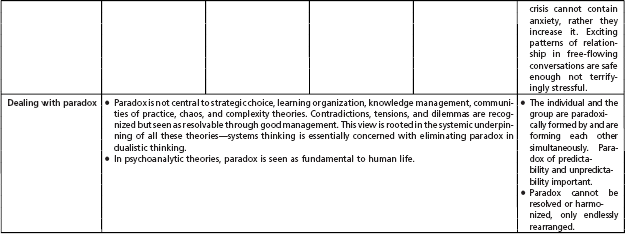

Table X-1. The concept of complex responsive processes of relating in organizations: The key underlying assumptions (adapted from Stacey, 2001, 2003).

| Assumptions about: |

The views on human nature:

Human psychology, the meaning of tacit knowledge and unconscious processes, the nature of memory and learning processes | - The fundamental motivator of human behavior is the urge to relate.

- There can be no human individual outside of relationship: the individual is decentered, yet not lost sight of.

- Makes a radical shift from the cognitivist view and humanistic psychology: individuals and groups form and are formed by each other simultaneously: Silent, private conversation (individual mind) is structured by and always resonating and changing with, public conversations in groups.

- The social and the individual are viewed at the same ontological level.

- Power relations, ideologies, fantasies, and emotions are central; theory of interaction and theory of human nature are the same.

- Intention is not an attribute of an individual, but emerges in conversational relationship, and is articulated by an individual.

- While in theories where the individual is primary, there is a tendency to equate agents with individual human beings and retain the orthodox notions of empowerment and delegation through the notion of self-organization, in CRPR the analogue of agents is themes that organize experience. Self-organization of these themes retains emergent unpredictability; causal dualism of systems thinking is replaced by paradoxical transformative causality of CRPR.

- Leadership is no longer an individual competence but a form of relationship.

|

The nature of human interaction:

Human relating in context, internal mechanisms of change, time dimension, prediction, level of analysis, diversity | - It is essentially communicative interaction: a process of communication and power relating.

- The interaction does not result in a whole/a system, but in further patterns of interaction (creating conditions of radical unpredictability).

- Spatial (static) metaphor of being inside/outside the system is replaced by a temporal metaphor of continual reproduction and potential transformation.

- Organizations and managerial action are fundamentally conversational in nature, forming and being formed by power relations.

- Unpredictability is central to this theory.

- The level of analysis is microlevel, focused on bounded instability in which through self-organization emergent novel forms of relating and conversation can be produced, creating new meanings and new knowledge.

- Microdiversity and creativity are recognised as essential for internal capacity to change spontaneously.

|

Methodological position:

Level of analysis and the view on the process of knowledge creation and its enactment in practice | - CRPR advocates the methodological position in which people are both participants and observers at the same time. A manager cannot stand outside organizational processes and control them, direct them, or perturb them in an intentional direction. Such intentions are only gestures made to others and what happens unfolds from ongoing responsesmethodology of emergent enquiry (Stacey, 2003, p. 413).

- Critical systems perspectives and some knowledge management and communities of practice approaches also adopt reflexive and participative methodologies: argue for co-constructed nature of knowledge and multiple perspectives on any situation. Still the human interaction is understood as producing a system where there is a strict delineation and dualism of position in and outside the system.

- The notion of the edge of the chaos in CRPR is not one where managers nudge/push the system into instability and crisis and put people under more stress until they are motivated to change and unleash the power of self-organization which removes stress. Here the edge of the chaos is free-flowing conversation, where the pattern of people's interaction provides good enough holding of anxiety in facing unknown. Stress and crisis cannot contain anxiety, rather they increase it. Exciting patterns of relationship in free-flowing conversations are safe enough not terrifyingly stressful.

|

Approach to paradox:

Between unpredictability and control; approach to time-flux/change | - The individual and the group are paradoxically forming and being formed by each other simultaneously. Paradox of predictability and unpredictability important in CRPR.

- Paradox cannot be resolved or harmonized, only endlessly rearranged.

|

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

I n this monograph we outline and discuss the process and findings of the inquiry into the implications of complexity theory for project management theory and practice, which was generously supported by the Project Management Institute (PMI). We wish to thank PMI for giving us this opportunity to engage in, and contribute to, the pertinent and lively discussion about complexity in and of projects, which seems to have emerged in response to the growing concern about the dominance of various versions of control theory, operations research, systems theory, and instrumentalism in the studies of projects, project management, and project settings in general. A growing body of extant critique, emerging propositions, and research trajectories has exposed deficiencies and controversies associated with the relevance of the traditional project management research to the challenges experienced in contemporary project environments and with its practical application at three levels: (1) discrepancy between project management best practice recommendations and what is really being enacted in practice; (2) observations of paradoxical, unintended consequences in practice that emerge from following the project management prescriptions in the book; and (3) the need for alternative theoretical conceptualizations and thinking about projects and project complexity in practice. During the past decade, there has been an increasing tendency to draw attention to the particular challenges posed by complex projects (Williams, 1999; Richardson, Tait, Roos, & Lissack, 2005) or by complexity in projects (Baccarini, 1996; Cicmil, 2003a, 2003b, 2005; Cicmil & Marshall 2005; Sommer & Loch, 2004). The discussion, however, has been somewhat hindered because the issue of theoretical foundations in project management research has been a central point of debate among both practitioner and scholarly communities for quite some time.