List of Tables

1.1 The Growth of Budget Outlays, Fiscal Years 19551982

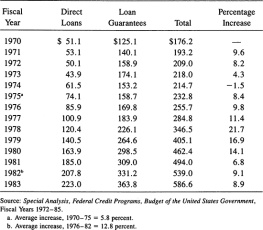

1.2 Outstanding Federal Loans, Fiscal Years 19701982

1.3 Gross versus Net Lending, Fiscal Years 19801982

1.4 Unified and Actual Budget Deficits, Fiscal Years 19741982

1.5 Federal Participation in Domestic Credit Markets

1.6 Average Loan Terms and Comparable Market Interest Rates, Direct Loan Programs, by Agency, 1982

1.7 Average Loan Terms, Selected Loan Guarantee Programs, by Agency, 1981

2.1 Budget Shares, Defense versus Payments for Individuals, Fiscal Years 19551983

2.2 Human Resources Spending, Fiscal Years 19701985

2.3 Direct Loan Obligations and Loan Guarantee Commitments, by Function, Fiscal Years 19501982

2.4 Major Loan Guarantee Programs, Fiscal Year 1982

2.5 Major Direct Loan Programs, Fiscal Year 1982

3.1 Federal Financing Bank Holdings, Outstanding Agency Debt, Fiscal Years 19751983

3.2 Outstanding Federal Financing Bank Holdings, Agency Debt, Loan Assets, Direct Loans, Fiscal Years 19761983

3.3 FmHA Lending, Budget Balances, and CBO Sales to the FFB, Fiscal Years 19741983

3.4 Outlay and Deficit Understatements Caused by FFB Financing, Fiscal Years 19741983

4.1 Credit Legislation Enactments, by Functional Category, 19651982

4.2 Outstanding Credit Advanced by Government-Sponsored Enterprises, 19701982

4.3 Current and Previous Off-Budget Agencies

5.1 Net Federal Credit and Federal Credit Control, Fiscal Year 1981 Estimates

5.2 Appropriations Bill Limitations, Fiscal Year 1981 Estimates

5.3 Outstanding Federal Credit and Net Federal Credit, Fiscal Years 19791981

5.4 House Budget Committee Credit Budget Recommendations, Fiscal Year 1981

5.5 Federal Credit Outstanding, Fiscal Years 19791981

5.6 Direct LoansCredit Budget versus Program Activity, Fiscal Year 1981

5.7 Loan GuaranteesCredit Budget versus Program Activity, Fiscal Year 1981

6.1 Reagan Administration and Congressional Spending and Credit Budget Aggregates, Fiscal Years 19811986

6.2 Estimated and Actual Changes in New Lending, by Agency, Fiscal Years 19801982

6.3 Reagan Administration Proposed Reductions in Credit Programs, Fiscal Years 19841988

6.4 Action Required to Effect Major Program Reductions, Reagan Fiscal 1984 Credit Budget

6.5 Estimated Outlay Impact of Reagan Credit Budget Proposals, Fiscal Years 19841988

6.6 Reagan Administration and Congressional Credit Budgets, by Function, Fiscal Year 1983

7.1 Interest Subsidy Values, Selected Direct Loan Programs, 1983

List of Figures

1.1 Net Federal Credit, Fiscal Years 19721988

2.1 Composition of the Spending Budget, Fiscal Years 19801985

2.2 Composition of Federal Spending and Federal Lending, Fiscal Year 1982

2.3 Total Guarantees Outstanding for Actuarially Sound Programs and for Programs for Marginal Borrowers

2.4 Federal Aid to Students for Higher Education, Fiscal Years 19711983

3.1 Net Lending and Loans Outstanding of the Federal Financing Bank, Fiscal Years 19741983

3.2 Direct Loan Disbursements, Farmers Home Administration, Fiscal Years 19511985

Preface

Each year, federal agencies distribute tens of billions of dollars in direct loans and guaranteed loans through a variety of credit assistance programs. There is disagreement about the effectiveness of many of these programs. There is also a good deal of uncertainty, and even growing apprehension, about their economic impact. While this book discusses the programmatic and macro-economic issues associated with federal credit activity, its focus is on the political implications of credit.

The budgetary treatment of federal credit programs has exacerbated spending-control problems in Congress and the executive branch. Since the volume and, more important, the subsidy costs of federal credit assistance are not accurately reflected in the unified budget, credit programs are not forced to compete with direct spending or even with tax preferences. When pressures develop to control budget totals, as has been the case in recent years, credit programs offer a loophole. Substantial amounts of financial assistance can be distributed to a wide range of borrowers with little or no direct budgetary costs.

The loophole is deliberate. The budgetary distortions and evasions relating to federal credit accounting are the products of design, not accident. They have been used to shelter programs that otherwise could not compete successfully for scarce resources. They have served to protect credit programs from critical oversight. They have, until recently, frustrated attempts to direct congressional attention toward the growth and impact of credit policy.

In the absence of external controls, such as constitutional limits, fiscal discipline is heavily dependent upon appropriate norms and procedures. In practical terms, this meansat a minimumcomprehensive budgets and centralized spending control. Credit programs have eroded the comprehensiveness of the federal budget and weakened still further centralized control over spending. Under these conditions the prospects for fiscal responsibility are dim. This is especially true in Congress, which has typically found it difficult to resist spending pressures.

For much of our history the fiscal test applied to political institutions was simple. Budgets should, under normal conditions, be balanced. Deficits should, if unavoidable, be temporary. The norm of the balanced budget reflected certain beliefs about government and the economy, but it was influenced to a considerably greater degree by political assumptions. So long as spending had to be financed directly and immediately by taxation, the political benefits of spending would be offset by the political costs of taxation. Given the public's natural antipathy toward taxes, balanced budgets meant limited budgets.

This norm, however, no longer applies to the federal government. The federal budget has become an instrument of economic management. Whether it is balancedwhich has occurred only four times in the past thirty yearsis not considered a test of political virtue or economic desirability. There is, then, a different fiscal test, with budgets evaluated for their economic impact. As is now quite apparent, this impact is much too uncertain to guide political decision making. Cutting the nexus between spending and taxation, and not substituting a clear-cut standard for evaluating fiscal decisions, simply biases the political process toward increased spending and deficits.