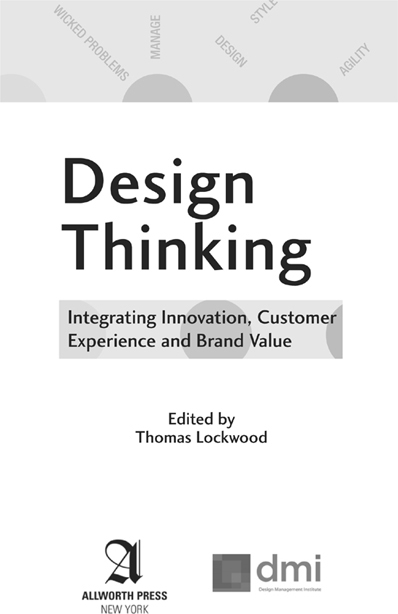

2009 Design Management Institute

All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Allworth Press

An imprint of Allworth Communications, Inc.

10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010

Cover design by Jon Craine and Alan Lee

Interior design by Alan Lee

Page composition/typography by SR Desktop Services, Ridge, NY

ISBN-13: 978-1-58115-668-3

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58115-734-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Design thinking : integrating innovation, customer experience, and brand value/

edited by Thomas Lockwood.3rd ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-58115-668-3

1. Industrial design. 2. Product design. I. Lockwood, Thomas.

TS171.4.D4865 2009

658.5752dc22

2009026966

Printed in the United States of America

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the creative class. To all the right-brainers out thereand the left-brainers with a creative sparkour opportunity to make a difference is now! There has been no greater time of need for social, economic, and environmental improvement than today, and no better people to make a difference than design thinkers: those who venture outside the box, who are open-minded, who enjoy collaborative ideation, who have an eye on design and an eye on the future, who have a passion for change, who tell visual stories, and who do all of these things with a spirit of goodness. We can make the world a much better place, by design, in every moment.

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to all of the contributing authors whose work is included in this book. Their professional insight and research is greatly appreciated and have made working on this manuscript a true pleasure. I would also like to thank all of the other contributing authors who have written articles for DMIs Design Management Journal and Design Management Review over the years. Equally, I would like to acknowledge the work of the former president of DMI, Mr. Earl Powell, who founded the DMI publications and served as their publisher until 2005, and Dr. Thomas Walton for his outstanding work as the editor of the Design Management Review since its inception. Collectively, all of these efforts have significantly increased our understanding of design management, thinking, strategy, and leadership, and advanced our knowledge about the important role of design in business.

Foreword

THE IMPORTANCE OF INTEGRATED THINKING

When our publisher suggested that I put together a book about design thinking, I wondered aloud: Hasnt someone already done this? Well, evidently no one has, at least not in the sense of the current meaning. The publisher asked when I first encountered the idea of design thinking. He was surprised when I answered that it was about thirty years ago, when I was a young designer at CAMP7, one of the leading manufacturers of down sleeping bags and mountaineering gear at that time.

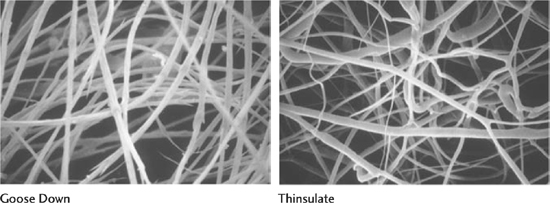

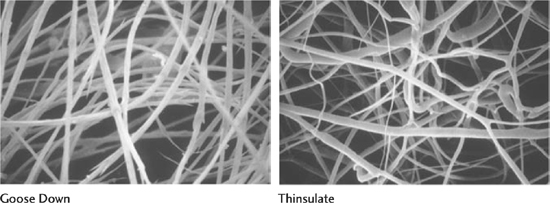

Years ago, state-of-the-art clothing for skiers and mountain climbers consisted of cotton long johns, wool sweaters, puffy down jackets, and a cotton/poly 60/40 outer layer that shed wind but not water. I was the head of design and development at CAMP7, and one day an engineer from 3M contacted me to discuss a new microfiber he was working with. We got to talking about clothing for outdoor sports, and he asked me if I knew why down keeps people warm. I realized that I did not. I thought it was something about those little puffy down pods, the more loft in them the better, but I finally had to admit that down equaled warmth to us in the industry, and in a way we basically thought of it as some kind of magic. But the 3M engineer knew much more than I did, and he explained that the magic was due to the combination of teeny-tiny nodes, which protrude from teensy-tiny barbules, which stem from the little tiny branches, which protrude from a single pod of down, which creates a tremendous amount of surface area, yet is invisible to the human eye. He even showed me microscopic photography of this. That day, the realm of scientific research arrived on the doorstep of the design of ski-wear and mountaineering gear.

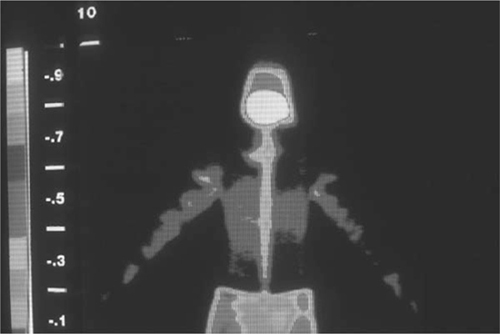

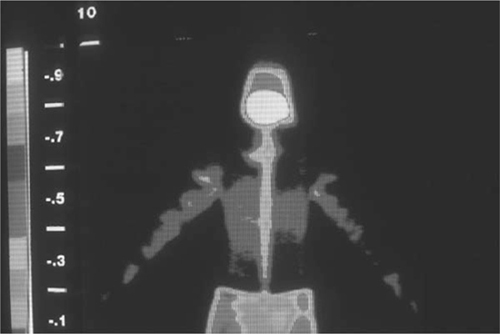

This new microfiber the engineer had brought with him was something he had developed while working on a project to invent better brushes for commercial floor scrubbers: a synthetic material with maximum surface area for more scrubbing friction. He gave me a few sample yards of material and asked if I could make some outdoor gear out of it. So we made clothing and sleeping bags, used them in the Colorado mountains, and found they kept us warm, even in wet snowy conditions. It turns out that the greater surface area stops air movement due to friction, and thus helps prevent heat loss. The engineer invited me to 3M headquarters, where they photographed our current products and our new prototypes using a form of photography they had just developed called thermography. With thermography, it was possible to see exactly where heat was being lost. We all got very excited about this.

Not long afterwards, I started a research collaboration with the University of Colorados physiology department to study heat loss in cold-weather conditions. I discovered that there was very little existing research about how and why people lose heat when exercising in severely cold weather. We recruited students to exercise in a very large walk-in meat freezer on campus by working out on stationary bikes and treadmills in front of large fans simulating wind chillreally difficult conditions. We tested new prototype synthetic materials and variations of product designs against the traditional wool, cotton, and down. The results amazed us. For the first time, we were able to provide scientific evidence of how certain synthetic materials, such as polypropylene and polyolefin, when developed as a microfiber, wick moisture away from the body and in doing so keep people warmer as they exercise in freezing temperatures than traditional natural materials do. The 3M prototype material, a microfiber polypropylene, was later named Thinsulate.

We also tested another prototype material, which had a waterproof and breathable synthetic membrane, but allowed more moisture transfer and actually kept our test students warmer in action. This material was later named Gore-Tex.

In the coming year, CAMP7 was the first company in the world to make skiwear from Thinsulate and combine Thinsulate with Gore-Tex, and to be able to prove that these worked better than the century-old status quo materials. One reason we were relatively fast to market was because our CFO was also an avid skier and wanted to be involved with the testing. So, while we evaluated various designs, he considered potential business opportunity scenarios with us. Although our rough prototype clothing was rather patchwork, it worked very well. Soon we added western-style GoreTex shoulder yokes over the prototype Thinsulate ski jackets, and these worked well even in wet, snowy conditions. We gave prototype samples to our friends. They used them on climbing expeditions. This soon got the attention of the U.S. Nordic ski team, which trained in the area. The team members tested our prototypes, helped refine the components into a layered system, and then used our radical new clothing in the Winter Olympics.