What Hedge Funds

Really Do

What Hedge Funds

Really Do

An Introduction to Portfolio Management

Philip J. Romero and Tucker Balch

What Hedge Funds Really Do: An Introduction to Portfolio Management

Copyright Business Expert Press, LLC, 2014.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other except for brief quotations, not to exceed 400 words, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2014 by

Business Expert Press, LLC

222 East 46th Street, New York, NY 10017

www.businessexpertpress.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-63157-089-6 (paperback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-63157-090-2 (e-book)

Business Expert Press Economics Collection

Collection ISSN: 2163-761X (print)

Collection ISSN: 2163-7628 (electronic)

Cover and interior design by Exeter Premedia Services Private Ltd., Chennai, India

First edition: 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America.

Abstract

What do hedge funds really do? These lightly regulated funds continually innovate new investing and trading strategies to take advantage of temporary mispricing of assets (when their market price deviates from their intrinsic value). These techniques are shrouded in mystery, which permits hedge fund managers to charge exceptionally high fees. While the details of each funds approach are carefully guarded trade secrets, this book draws the curtain back on the core building blocks of many hedge fund strategies. As an instructional text, it will assist two types of students:

Economics and finance students interested in understanding what quants do, and

Software specialists interested in applying their skills to programming trading systems.

What Hedge Funds Really Do provides a needed complement to journalistic accounts of the hedge fund industry, to deepen the understanding of nonspecialist readers such as policy makers, journalists, and individual investors. The book is organized in modules to allow different readers to focus on the elements of this topic that most interest them. Its authors include a fund practitioner and a computer scientist (Balch), in collaboration with a public policy economist and finance academic (Romero).

Keywords

absolute return, active investment management, arbitrage, capital asset pricing model, CAPM, derivatives, exchange traded funds, ETF, fat tails, finance, hedge funds, hedging, high-frequency trading, HFT, investing, investment management, long/short, modern portfolio theory, MPT, optimization, quant, quantitative trading strategies, portfolio construction, portfolio management, portfolio optimization, trading, trading strategies, Wall Street

Contents

Chapter 7 Framework for Investing: The Capital Asset

Pricing Model (CAPM)

Chapter 8 The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)Its

Three Versions

Chapter 9 The Fundamental Law of Active Portfolio

Management

Chapter 10 Modern Portfolio Theory: The Efficient Frontier

and Portfolio Optimization

Chapter 12 Overcoming Data Quirks to Design

Trading Strategies

Strategies

Chapter 15 Hedge Fund Case Study: Long Term

Capital Management (LTCM)

George Soros, a poor Hungarian immigrant with a philosophers bent and a London School of Economics degree, founded Quantum Capital in the late 1960s and led it to breathtaking returns, famously breaking the Bank of England in 1992 by shorting the pound sterling. Julian Robertson, the hard-charging North Carolina charmer who made huge contrarian bets on stocks, built the Tiger Fund in the 1970s and seeded dozens of Tiger Cubs that collectively manage hundreds of billions of dollars. John Meriwether left Salomon Brothers to collect a stable of PhDs in quantitative finance from University of Chicago to form the envied, and later notorious, Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). Each of these groups earned persistent returns for their investors that exceeded 30 percent per year, handily trouncing the market indexes. Each of their partners became billionaires, likely faster than ever before in history.

Each of these financial legends, and hundreds of other lesser-known investors, built a hedge fund . Private pools of funds have existed for as long as liquid capital marketsat least 800 yearsbut the first hedge fund is generally thought to be Albert Winslow Jones hedged fund, formed in the late 1940s. Since then, the number of such funds has grown into the thousands, and they manage trillions of dollars in clients funds.

Hedge funds are the least understood form of Wall Street institutionpartly by design. They are secretive, clannish, and less visible. Hedge funds have received a generous share of envy when they are successful and demonization when financial markets have melted down. But whether you wish to join them or beat them, first you need to understand them, and how they make their money.

Hedge funds are pools of money from accredited investorsrelatively wealthy individuals and institutions assumed to have sufficient sophistication to protect their own interests. Therefore, unlike publicly traded company stock, mutual funds, and exchange traded funds (ETFs), hedge funds are exempt from most of the laws governing institutions that invest on behalf of clients. Implicitly, policy makers seem to believe that little regulation is necessary. The absence of scrutiny has helped hedge funds keep their trading strategies secret.

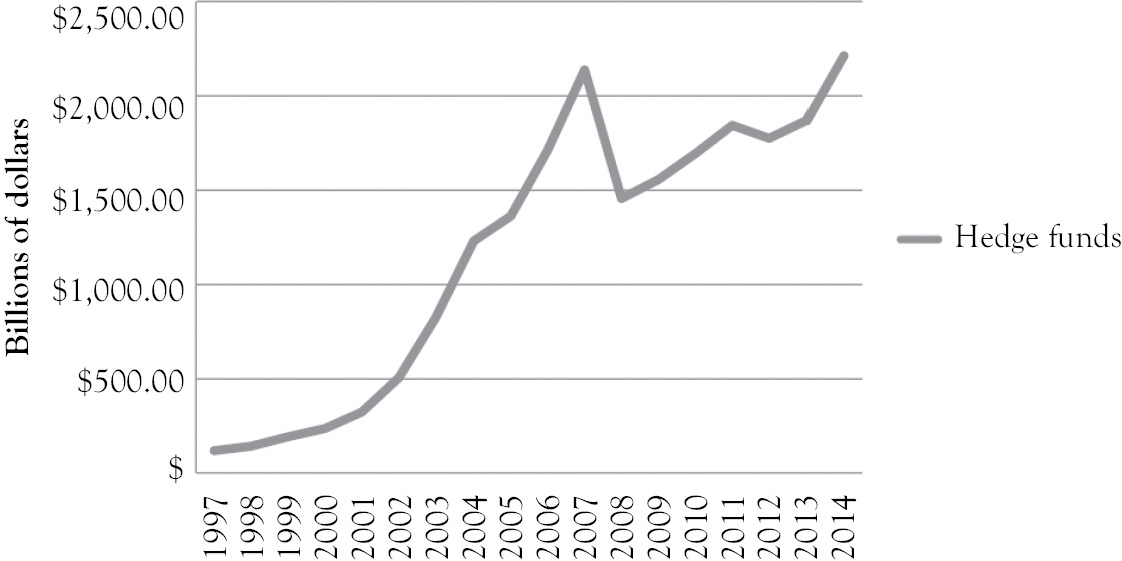

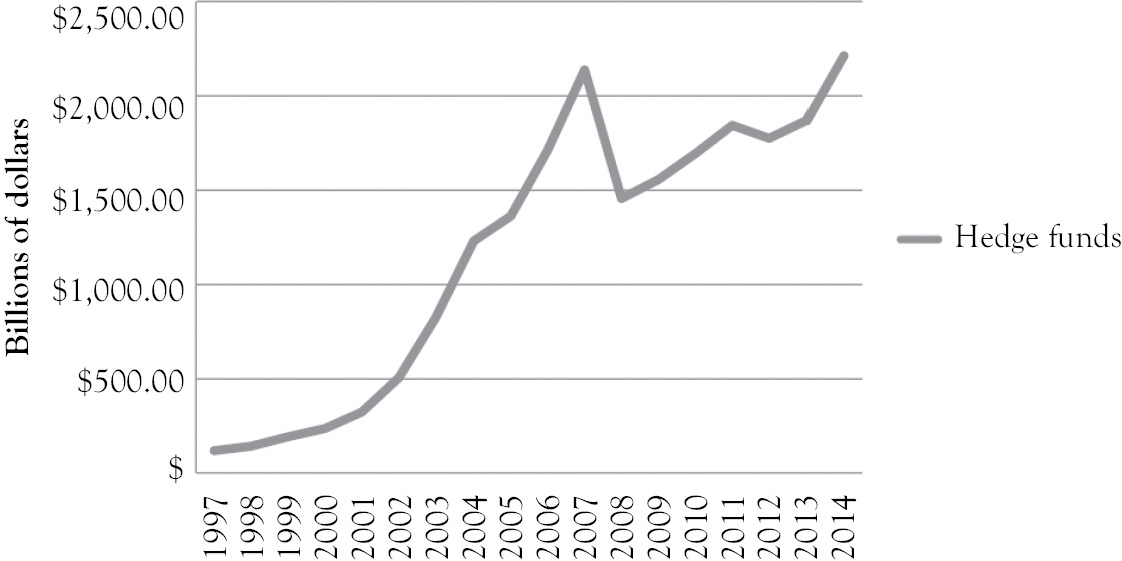

Figure 1.1 Total hedge fund assets under management, 1997 to 2013

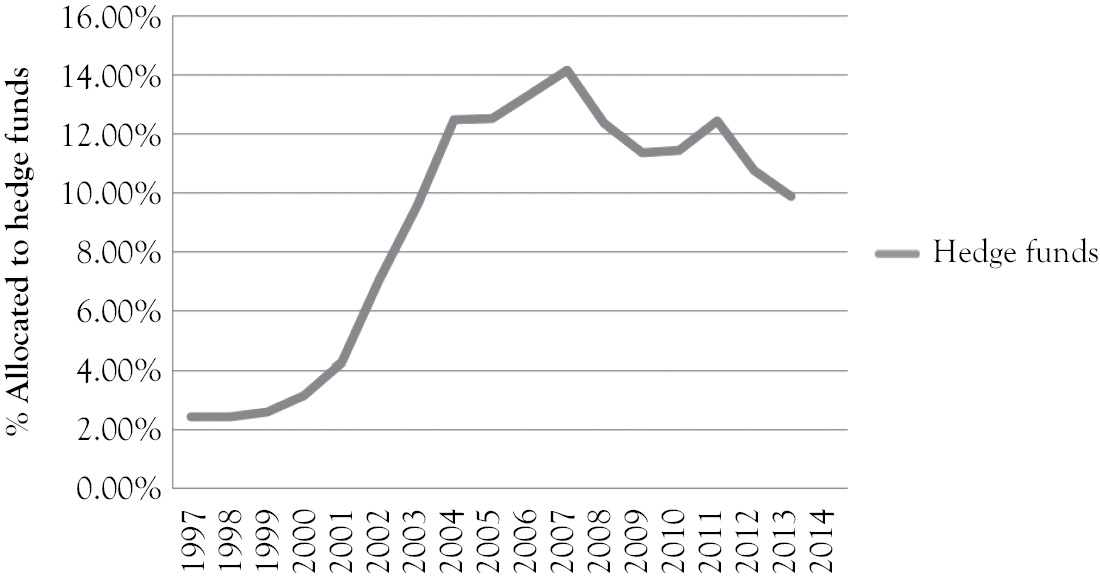

The scale of hedge funds has grown tremendously in the past few decades, as illustrated in ).

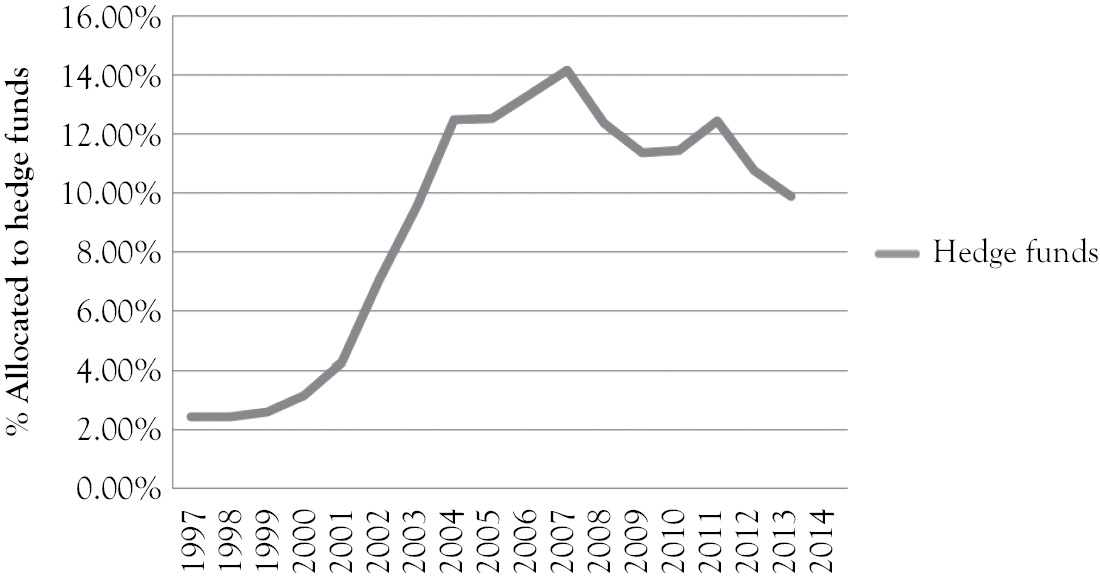

Figure 1.2 Hedge funds compared with other asset classes

These lightly regulated funds continually adopt innovative investing and trading strategies to take advantage of temporary mispricing of assets (when their market price deviates from their intrinsic value). These techniques are shrouded in mystery, which permits hedge fund managers to charge exceptionally high fees. While the details of the approach of each of the funds are carefully guarded trade secrets, this book draws the curtain back on the core building blocks of many hedge fund strategies. As an instructional text, it will assist two types of students:

Economics and finance students interested in understanding what quants do, and

Software specialists interested in applying their skills to programming trading systems.

A number of fine journalistic accounts of the industry existand should be read by anyone interested in understanding this industrywhich offer interesting character studies and valuable cautionary tales. These include The Quants by Scott Patterson (2010), The Big Short and Flash Boys by Michael Lewis (2010 and 2014, respectively), More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and The Making of the New Elite by Sebastian Mallaby (2010), and When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management (2000) by Roger Lowenstein. But none dives very deeply into how quantitative strategies work. Many readers seek such tools so that they can improve current practicefrom the inside, at hedge funds; or from the outside, as regulators, journalists, or advocates.