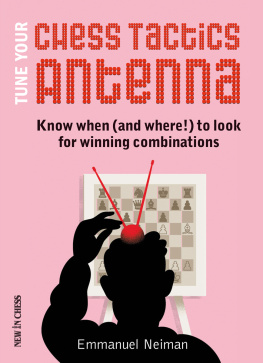

Tune Your Chess Tactics Antenna

Q 2012 New In Chess

Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands

www.newinchess.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher.

Cover design: Volken Beck

Supervisor: Peter Boel

Proofreading: Ren Olthof

Production: Anton Schermer

Have you found any errors in this book?

Please send your remarks to editors@newinchess.com. We will collect all relevant corrections on the Errata page of our website www.newinchess.com and implement them in a possible next edition.

ISBN: 978-90-5691-404-2

Foreword

In this book, I suggest a thinking method that is intended to help the practical chess player. I am sure that using this technique, the reader will improve his play as a whole, meaning both his tactical abilities (i.e. the ability to foresee combinations) and his positional abilities.

The idea of this work is to provide the reader with a kind of antenna. This antenna has seven filters (what I call signals) that will allow a chess player to detect tactical possibilities.

The two main points are:

- Follow carefully the necessary steps of reflection (see the 5 phases in the Introduction);

- Detect the signals for you and for your opponent (Part I and II).

First look, then analyse, plan, and only then start to look for the right move! See Part III of this book.

A great trainer and champion once advised his pupils to calculate like machines. Id say: be human! Do not calculate without ideas.

Good luck to all!

Emmanuel Neiman

November 2012

Footnote

Alexander Kotov.

Explanation of Symbols

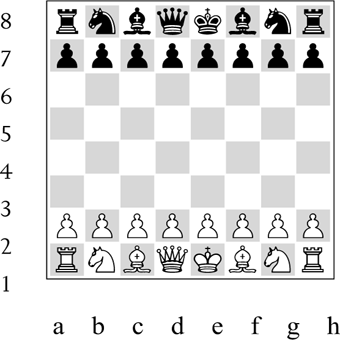

The chess board with its coordinates:

White to move

Black to move

! Good move

!! Excellent move

? Bad move

?? Blunder

!? Interesting move

?! Dubious move

White stands slightly better

White stands slightly better

Black stands slightly better

Black stands slightly better

White stands better

Black stands better

+ White has a decisive advantage

+ Black has a decisive advantage

= balanced position

unclear position

# checkmate

Introduction

Improving the ability to solve chess combinations is the main road to progress for the learning chess player. As soon as he is given the magic formula White to play and win, the seeker will try to find as quickly as possible the best move in order to provoke events and in so doing, he will improve his capacity to calculate forced lines.

After some practice, in general the improvement is significant and as a trainer I am often surprised by the ability of some people to quickly find the solution to a non-obvious puzzle.

When I congratulate a pupil on good solving, his/her reaction is often: That was not difficult, you told us that there was a combination! Most of them add: The real problem is that when we are playing, we dont know when to look for a tactic. This started me thinking about the idea of an antenna that alarms a player when a combination is available.

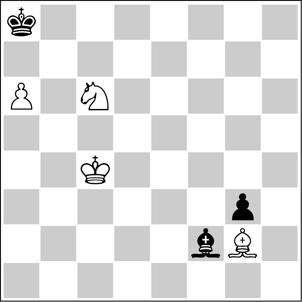

Once I found in a newspaper the following position, which I gave to grandmaster Anatoly Vaisser to solve:

Lingnau,Carsten

Orso,Miklos

Budapest 1992 (4)

White to play and win

One, maybe two seconds after I showed him the position, he indicated the right solution by drawing a kind of Z with his finger in the air.

Nevertheless, in the actual game White was unable to win, and had to be content with a draw after

65.Kd5 Bg1 66.Ke6 Bf2 67.Kd7 Bg1 68.Kc8 Be3 69.Na5+ Ka7 70.Bb7 g2

-

Here we have a basic illustration of our theme. White was not advised that there was a forced win, so he just continued in the logical way, bringing his king toward the enemy monarch.

What did Vaisser immediately detect here?

We can observe, before doing any calculation, that the black king is already stalemated by the knight on c6 and the pawn on a6. This observation should lead us to look for some chance to give check without moving the two guards (knight and pawn). Then we might notice that the light-squared bishop is able to deliver the mate, for it can reach the b7-square via the route h3-c8-b7 and mate.

Did Vaisser follow all these steps?

I doubt it in one or two seconds. What (as I think) he did instantly was just:

1. Checking the enemy king position.

2. Looking for a mating possibility.

3. Seeing the right route.

Is it the same process?

No, the trained grandmaster (at this time, Vaisser was one of the best rapid players in the world), knowing that there is something to be found, concentrates on the essential. First, the king! Probably, almost immediately after he is given the diagram position, he looks for a mate, because he instantly realizes that the black king is trapped.

If you tried some fancies along the long diagonal, or, like in the actual game, started a long march with the king, then you did not investigate the most crucial problem in the position (and most generally in chess): the kings position.

I hope that after reading this book, you will go for the real stuff in this kind of position, and that before looking for moves, you will look for ideas.

Here the idea is relative to the poor kings position. Such an idea is classically called the motif of a combination. The motif is the reason why theres a combination or a forced win (a combination normally implies a sacrifice, here we look for tactics that is, a forced variation with or without a sacrifice).

Generally, puzzle books are arranged according to theme. This classification: double attack, pin, deflection, decoy, etc., is a useful tool for solving purposes. When we know that there is a combination, the motif provides a valuable answer to the How. In this book, we deal with the Why: we want to discover if there is a chance of winning by force.

We are looking for hints, and if we can find some, then we will look at the position with a solvers eyes a solver who has already done part of the job. The antenna has been erected, and it involves seven filters. In classical chess literature these filters are called motifs. In this book, in accordance with our antenna theme, we will call them signals.

A. What is a signal?

A signal is a weakness in the opponents position.

When we look for a signal, we look for a reason why we should be winning. Since Steinitz, we know that the combination does not appear randomly, but as a consequence of the positional superiority of one side. This superiority lies in positive factors, lets say more active pieces. But we can take the opposite approach: looking at the opponents position, we can establish that he has passive pieces; or they may be trapped, locked in or lacking coordination. This way of looking gives us hints, and those hints we will call signals, in other words: reasons to believe that there is a possible win.

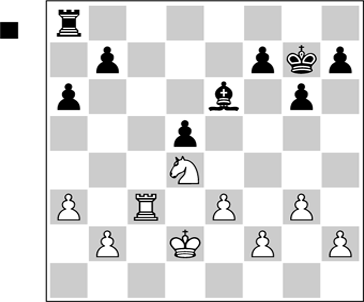

Take another position:

Next page

White stands slightly better

White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better

Black stands slightly better