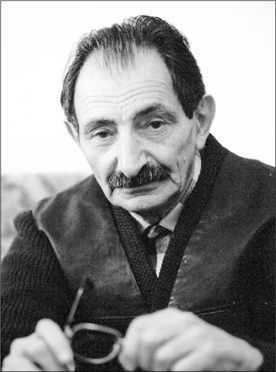

About the Author

Born in Moscow in 1923 and raised there, Yakov Isayevich Neishtadt became a living legend in Russian chess. He was already a first-category player at the beginning of World War II, but then he had to serve his country in battle. After the war he started to play in tournaments again and became a master of sports of the USSR as well as a world-class correspondence chess player and an arbiter.

But Neishtadt is best known as an outstanding chess journalist. He has written more than twenty opening books, which have been published in a dozen languages. From 1955 to 1973 he was secretary of the magazine Chess in the USSR , and from 1977-1979 an editor of the famous Soviet chess magazine .

In 1992 Neishtadt moved to Israel with his family. There he is still writing books. Genna Sosonko, in the article Yakov Neishtadt at 80 in his book Smart Chip from St. Petersburg (New In Chess, 2006), called him a living treasure-trove of history, anecdotes, incidents, events, memories of people, sketches.

Explanation of Symbols

| White to move |

| Black to move |

| ! | Good move |

| !! | Excellent move |

| ? | Bad move |

| ?? | Blunder |

| !? | Interesting move |

| ?! | Dubious move |

| K | King |

| Q | Queen |

| R | Rook |

| B | Bishop |

| N | Knight |

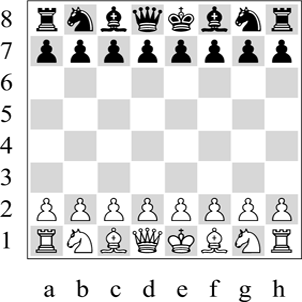

The chess board with its coordinates:

The Alpha and Omega of Chess

Strategy and tactics. The definition of a combination. Classification.

Right from the very first page of most chess books, in almost every comment we encounter special terminology, without thinking much about their derivation and basic meaning.

A chess game is an ideal representation of war, in which the sides (as distinct from a real war) follow clearly-defined rules. The majority of the terms we use in chess are derived from military lexicon. Tactics and strategy. Attack and defence. Counter-attack. Flanks and the rear. Fortress, siege, blockade, breakthrough, penetration, etc.

STRATEGY is the most important part of the art of war, devoted to the preparation and carrying out of military actions, and the planning of operations. TACTICS is the art of conducting a specific battle. Because the specific battle is part of the overall (strategic) operation, tactics serve strategy, and fulfil its tasks.

In this sense, chess strategy should occupy itself with planning, and the selection of the targets at which our play should be directed in the given position. Tactics are the specific concrete actions which we have to carry out to achieve our desired aims. In the words of Max Euwe, the distinction is between what to do and how to do it.

In a word, tactics serve strategy and depend on it. Compared with a war situation, the chess definitions have a slightly different sense.

Tactics do not embrace all concrete operations (for example, exchanges), but only actions of a sharp, combinative character, intended to change significantly the picture on the board, or to decide the games outcome. In this sense, it does not matter whether the tactical operation is the logical outcome of events (i.e. whether it fits in with the strategic plan) or whether it is unconnected with the general flow of the game, and arises randomly (for example, because of a blunder by the opponent in a position that is better for him).

In other words, tactics in chess do not always serve strategy sometimes they exist of their own accord. Separate manoeuvres, aimed at fulfilling the strategic plan, are not usually regarded as part of tactics. In general, the terms tactics and strategy, and, correspondingly, tactical play and strategic play are used almost as synonyms. When starting out using chess literature, it is worth remembering this change in military (and even political) terminology.

And now we turn to the play itself.

Note: Throughout the book, we will use squares to the left of every diagram to indicate which side is to move.

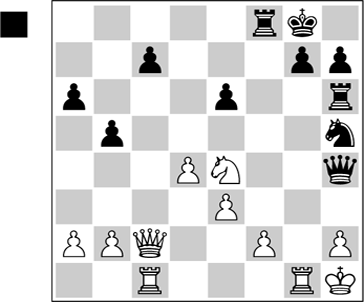

1 Manca

Braga

Reggio Emilia, 1992/93

The queen was sacrificed 1.Qc7+! , and the game ended. Black is mated: 1Nxc7 2.Nb6+ axb6 3.Rd8#.

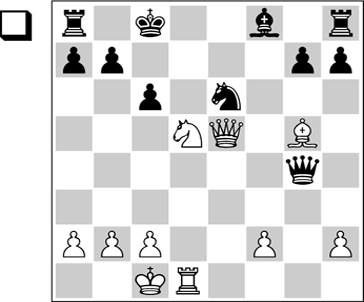

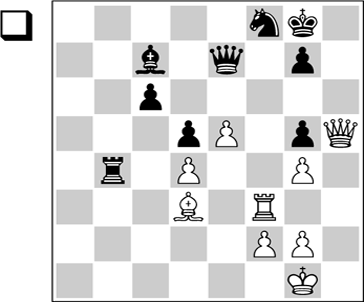

2 Siegel

V. Mikhalevski

Neuchatel, 1996

White thought his opponent had nothing better than to take the knight. However, there followed 1Bh4+! 2.Kxh4 2.Kf3 Qf2#. 2Qf2+ 3.Kg5 h6+ 4.Kxh6 Qh4# .

In the following examples, after the sacrifice, there follow only checks and forced replies.

3 Durao

Catozzi

Dublin, 1957

Black was mated elegantly: 1.Rf4+ Kh5 2.Rh4+! gxh4 3.g4#

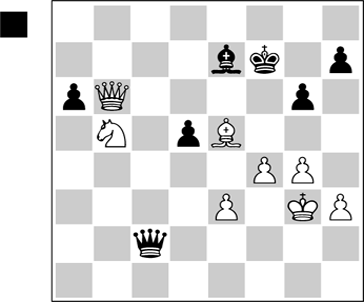

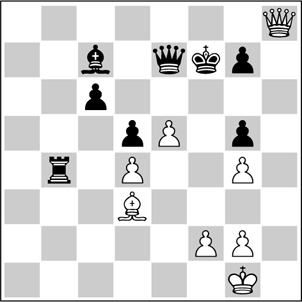

4 Cruz Lima

A. Hernandez

Cuba, 1994

Here Black announced mate in five: 1Qxh2+! 2.Kxh2 Nf4+ 3.Kg3 Rh3+ 4.Kg4 h5+ 5.Kg5 Rf5#

In the following example, the king is mated after two sacrifices.

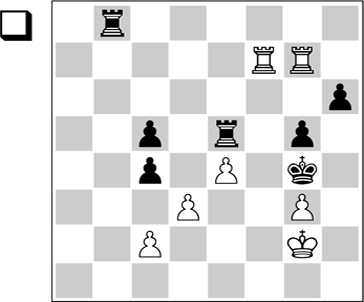

5 Geller

Novotelnov

Moscow, 1951

1.Rxf8+! Kxf8 If 1Qxf8 2.Bh7+ Kh8 3.Bg6+ and 4.Qh7#. 2.Qh8+ Kf7

3.Bg6+! Inviting the king into the mating net. 3Kxg6 3Ke6 4.Qc8+ (or 4. Qg8+ Kd7 5. Bf5+ Qe6 6. Qxe6+ Kd8 7. Qd7#) 4Qd7 5.Bf5+ Kf7 6.Qxd7+ Kf8 7.Qd8+ and 8.e6# does not change things. 4.Qh5#

Moves (or series of moves) connected by a general idea and logically connected with one another, are called a variation . When one side forces the others moves, this is a forcing variation . In all of the examples we have seen, the forcing character of the struggle resulted from a sacrifice. A combination is a forced variation with a sacrifice .

Arguments about formulae have no real connection with practical play. But these definitions are the basis for the classification of combinations, and, correspondingly, for the construction of our account of this important theme.

So far, we have deliberately chosen combinations in which every move is a check. Checks are a powerful means of control, of limiting the opponents choice of replies. Calculating a combination in which the enemy king is continually chased around with checks (especially if the main line has few, if any, deviations) is usually quite easy. However, such chances occur relatively rarely. Other means of control are threats and captures (exchanges). Decisive threats can also be set up by quiet (i.e. outwardly unremarkable) moves.