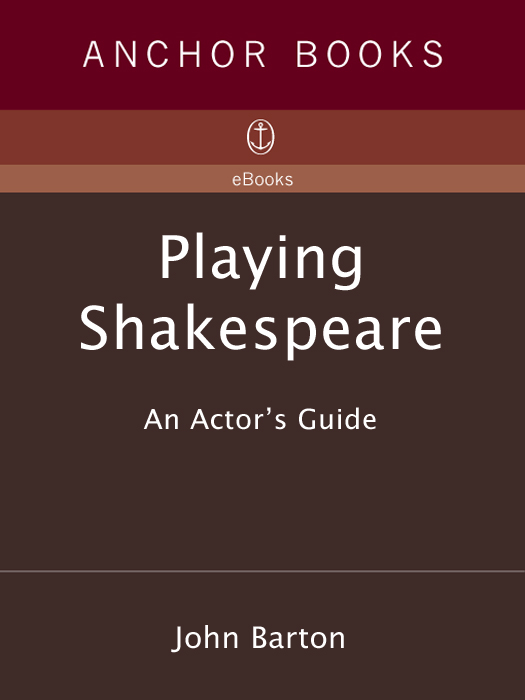

JOHN BARTON

John Barton has been associate director of the Royal Shakespeare Company for more than forty years and has directed more than fifty productions. He lives in London and conducts Shakespeare workshops throughout the United Kingdom and the United States.

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, AUGUST 2001

Copyright1984 by John Barton

Foreword copyright1984 by Trevor Nunn

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published simultaneously in hardcover and paperback in Great Britain by Methuen Publishing Limited, London, in 1984.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barton, John.

Playing Shakespeare / John Barton; with a foreword by Trevor Nunn.

p. cm.(A Methuen paperback)

Originally published: London: Methuen Drama, 1984.

eISBN: 978-0-307-77391-3

1. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Dramatic production.

I. Title. II. Series.

PR3091 .B37 2001

792.95dc21 00-052597

Author photographSimon Chapman

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

Contents

Actors

who took part in Playing Shakespeare

PEGGY ASHCROFT

TONY CHURCH

SINEAD CUSACK

JUDI DENCH

SUSAN FLEETWOOD

MIKE GWILYM

SHEILA HANCOCK

LISA HARROW

ALAN HOWARD

BEN KINGSLEY

JANE LAPOTAIRE

BARBARA LEIGH-HUNT

IAN M C KELLEN

RICHARD PASCO

MICHAEL PENNINGTON

ROGER REES

NORMAN RODWAY

DONALD SINDEN

PATRICK STEWART

DAVID SUCHET

MICHAEL WILLIAMS

Foreword

ForewordThe young man with the Renaissance face was John Barton. I had heard of him, of course, but there on the stage of the Arts Theatre Cambridge, directing a battle scene for a Marlowe Society production, was the man himself, with tapered trousers and bulky cardigan, giving him a seventeenth-century silhouette confirmed by a noble beard, high forehead, an expression in the eyes both haught and hawk and rich brown crinkled hair. He was Essex or Raleighdashing, formidable and in bursts of energy, like a whirlwind. My mental picture of my first sighting of John Barton betrays something of the impressionable eighteen-year-old student I was, and something of the need eighteen-year-old students have for legends, and larger-than-life heroes and enemies. In 1959 John was a Cambridge legend; he had directed countless university productions to professionally high standards, he had become a young and romantic don as the Lay Dean of Kings, with the Elizabethan Theatre Company he had pioneered small-cast touring Shakespeare productions, and he had been invited to become a founder-director of the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon. None of that of course contributed much to the legendno, it was the fact that he chewed razor blades for fun, that he knew every line of the First Folio by heart, that he spoke Chaucers English, that he was a brilliant and extremely dangerous sword fighter, that he was hilariously absent-minded, obsessed with cricket, a chain-smoker, an expert on Napoleon and somebody who enjoyed working sixteen hours a day without a break.

A lot of water has flowed under the bridges of the Cam since then; my need for heroes has diminished, while my regard for John Barton has increased. For much of the intervening time, since 1964 in fact, we have worked for the same company; we have shared similar ideals about the training and development of actors; we have collaborated on productions; we have asked for each others aid when things have gone wrong and we have become fast friends as much through adversity as through the sweet smell of success. And to the best of my knowledge John has given up chewing razor blades.

In 1965 I had a formative experience. I had been working for the RSC for a year. I had altogether lost my way and was suffering a crisis of confidence. John Barton proposed to me that he and I should collaborate on a reworking of Henry V, which had been part of the famous Stratford history cycle the previous year. For the six weeks of the rehearsal period I became the world expert on Johns absent-mindedness, I came to love the sixteen-hour day (I was already O.K. on cricket and Napoleon) and I learned more about unlocking a Shakespeare text than any scholarship could have taught me. I had always thought of Henry V as a role full of splendid and necessary rhetoric. Under Johns direction, the mighty set speech we know as Crispins Day, for example, became the spontaneous, almost desperately improvised attempt by a young leader to hold the morale of his men together as they stared at inevitable defeat; and instead of there being any sense that the actor was delivering a previously written text, Ian Holm, as Henry, thought and discovered those words out of the situation and of his character. Every clue of where to breathe, what to stress, when to run on, what to throw away was there in the text, if only like John you knew what to look for. But the poetry was not an end in itself. The words became necessary. It wasnt verse speaking. It was acting.

In 1979 John and I collaborated in a way that was new to both of us; we accepted Melvyn Braggs invitation on behalf of London Weekend Television to make a program about the difficulties and techniques of speaking verse, and together with Terry Hands and a small group of RSC actors, we conducted a session in front of an audience similar to the demonstration lectures all of us had done years previously as part of our companys work in education. The material we shot was sufficiently interesting to make Melvyn decide that it should become not one, but two programs and Word of Mouth, Parts 1 and 2, was duly transmitted to considerable acclaim in 1980.

The actors were articulate, Terry and I did what was required of us, but the star of the programs was John Barton, partly because he appeared not to know that the cameras were there, and partly because he did know so much more about the subject than all the rest of us put together. A series was proposed. John and I attended many hours of meetings delineating a structure and content for thirteen programs, but shortage of money and studio time postponed the whole project. I was relieved and delighted when the idea was taken up again and although I was unavailable to contribute, John agreed to make it his main RSC task for the second half of 1983. It was a very happy accident.

What the programs, and now the published texts of the series, reveal, is the method and principle of an approach to acting Shakespeare which has been fundamental to the Royal Shakespeare Company since it was formed. This approach is not didactic or political or scholastic or literary. It relies a good deal on analysis, but just as much on common sense and pragmatism, and a sense of theater and of character; it attempts to serve the complexities and contradictions of the text, but it is also trying to make the language