To my family and neighbors who have supported me through good times and bad, and to all the people who have inspired me and taught me along the way

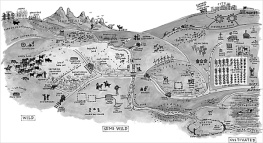

On too many farms, the most productive soils are growing crops, while the least productive soils are the ones put to pasture.

Why is the average acre of corn so productive and the average acre of pasture not so productive?

In 2017 David Hula of Charles City, Virginia, set a new world-record corn yield of 542 bushels an acre. This impressive feat received a considerable amount of attention and press, and deservedly so. It restores my faith in our country when someone such as a farmer, who actually produces a useful product for the human race, gets some attention. To put this farmers accomplishment into perspective, the national average corn yield in 2015 was 168.8 bushels an acre, so Hulas yield was more than three times the national average.

It is also impressive to look at the progress we as a country have made in corn yield and corn production technology in the past century. Its a very different story with pasture.

Grass versus Corn: The Roots of the Matter

Lets go back in time to explore how our experts and our technology have focused on improving corn and grain production but largely ignored grass and other livestock forage.

History of Corn Production 101

In 1900, corn was planted in 40-inch rows, at 40 inches apart within the row, to allow weed control via cross cultivation by a horse-drawn implement (the average width of a horse being 40 inches). This meant the corn population was around 3,900 plants per acre. The genetics of the day were all inbred, open-pollinated landraces. Fertility for corn was often provided by plowing down a prior crop of clover for nitrogen and perhaps an application of barnyard manure. There were no insecticides, no herbicides, no fungicides. Weeds, diseases, and insects all took their toll.

In 1900, the national average corn yield was 29 bushels per acre.

In 1960, corn was planted with a tractor in 30-inch rows (the standard width of a tractor tire), and populations of new hybrid varieties had increased to about 16,000 seeds per acre. Weed control was achieved by a combination of tillage and the new herbicides 2,4-D and atrazine. Fertility was supplied by synthetically produced urea and anhydrous ammonia, mined potassium chloride, and mined phosphate rock treated with sulfuric acid. DDT controlled insects.

In 1960, the national average corn yield was about 58 bushels per acre.

In the early years of the 21st century, corn is typically planted at 32,000 genetically modified hybrid plants per acre. Seeds are often planted without tillage, and weeds are controlled entirely by chemicals, since the corn is genetically engineered to resist the broad-spectrum herbicide glyphosate. The crop is protected from insect damage by the plant itself, because it contains a gene, obtained from a soil bacterium, that makes the plant produce a natural insecticide. All field operations are guided by global positioning units that prevent skips and overlaps in the field.

In 2015, the national average corn yield was 168.8 bushels per acre.

History of Beef Production 101

Now let us contrast the history of corn production with the production of beef cows on pasture in my area.

In 1900 in north central Kansas, cows were turned out to pasture in early May and given 6 acres of native grass apiece. They were left on this pasture until the corn was harvested in fall, after which the cows were brought home and the calves were weaned. The cows were pastured on cornstalks for a couple of months, then fed hay for 4 months.

In 1960, cows were turned out to pasture in early May and given 6 acres of native grass apiece. They were left on this pasture until the corn was harvested in fall, after which the cows were brought home and the calves were weaned. The cows were pastured on cornstalks for a couple of months, then fed hay for 4 months.

In 2015, cows were turned out to pasture in early May and given 6 acres of native grass apiece. They were left on this pasture until the corn was harvested in fall, after which the cows were brought home and the calves were weaned. The cows were pastured on cornstalks for a couple of months, then fed hay for 4 months.

In other words, pasture management has not changed in more than 100 years.

Is it little wonder a pasture is considered a low-producing acre and that so much of it has been plowed up to be converted to better use?

And yet, I will contend that pasture has more potential for yield and for profit than the current darling of American agriculture, corn.

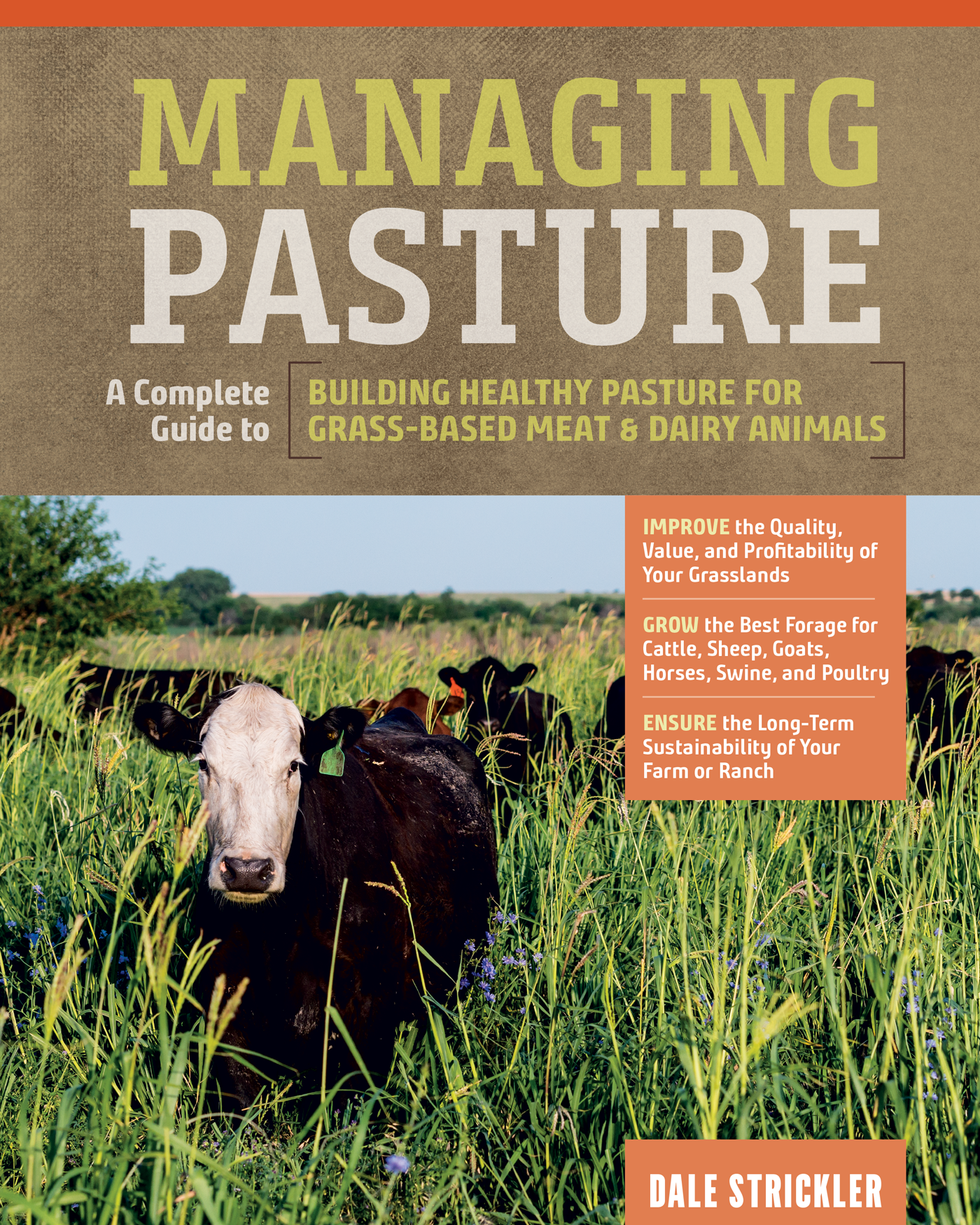

The newly seeded pasture to the right receives just as much rainfall and sunlight as the corn next to it on the same soil. Is there any reason the pasture could not be just as productive and profitable as the corn?

Management and Productivity

David Hulas record yield of 542 bushels per acre, at 56 pounds per bushel, produced an astonishing 30,352 pounds of grain per acre, or more than 15 tons. It is safe to assume that his stalks produced another 4 tons per acre of biomass, although Hula did not measure this. Consider this, however: those corn plants, sown in April, did not reach full size until June and then probably black-layered (reached full maturity) by early September. This means that there were only about 90 days of fully utilized sunlight on that acre of David Hulas record-breaking corn.

In case you need a refresher, there are 365 days in a year, and the sun shines on most of them. There is enough heat to grow some plant species in Charles City, Virginia, for up to 10 months out of the year. But Hulas corn achieved that yield in just 3 months of fully utilized sunlight and heat. What is the true potential of an acre if the entire growing seasons worth of sunlight is fully utilized? What if sunlight could be captured and converted into plant material every single day that the temperature is above freezing?

Why is the average acre of corn so productive and the average acre of pasture is not? The acre of corn on Hulas property received no more rain and no more sunlight than an acre of pasture just down the road. Why does the pasture not produce as much vegetative yield as the corn? Obviously, I am trying to lead you to the conclusion that it is because we do not manage pasture with the same intensity as we manage corn.