PRAISE FOR

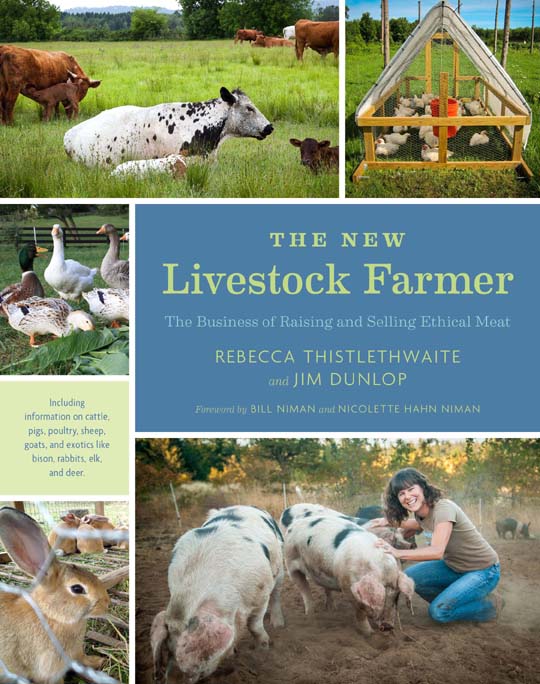

The New Livestock Farmer

Great practical advice on choosing the species to raise, humane treatment, and marketing. Informative chapters on processing, regulations, and starting a business.

Temple Grandin, author of Humane Livestock Handling and

Improving Animal Welfare: A Practical Approach

Responsible and healthful meat consumption starts on the farm, literally from the ground up, with solid and ethical animal-husbandry practices. The New Livestock Farmer provides a clear understanding of how to achieve fulfilling and delicious results. The authors share their proven wisdom to help small-scale, grass-based farmers avoid the pitfalls of an often confusing and intimidating agricultural landscape.

Adam Danforth, author of Butchering Beef and

Butchering Poultry, Rabbit, Lamb, Goat, and Pork

When it comes to raising healthy livestock in harmony with the land and the local community, this book shows why the old ways are new again... and why they work better than the industrial methods that are all too popular today. The detailed instructions in these pages are all you need to start raising livestock ethically and sustainably. In fact, Id say its a better investment than an agricultural degree from a land-grant university.

Mike Callicrate, owner, Callicrate

Cattle Co. and Ranch Foods Direct

My husband and I have farmed for a living all of our adult lives, and farmed with our parents before that. So we had the good fortune of being surrounded by people with deep generational knowledge when we started out. I cant imagine how new farmers are making it today without that kind of support. Recently we added Large Black hogs to our small farm in North Central Kentucky. The New Livestock Farmer came to us just when we needed it. It is what my father, Wendell Berry, would call the best of books because it is a tool. It fills a cultural need, and will give beginning farmers just the information they need, just the way they need it.

Mary Berry, executive director, The Berry Center

The livestock farmer of today must master not only the vast skills necessary to be an ethical rancher but also marketing, sales, processing, packaging, and so many others. Rebecca and Jims book is a humble and deeply informative guide from a couple that has been deep in the metaphorical and literal weeds of this challenging work. Without thriving agricultural-based communities, resources like this book are invaluable substitutes, creating a network of like-minded land stewards. Rebecca and Jim have done a good turn in sharing their knowledge in this straightforward and honest primer.

Marissa Guggiana, cofounder, The Butchers Guild, and

author of Primal Cuts: Cooking with Americas Best Butchers

The real question for the reform of livestock agriculture in the US is whether we can move from a media saturated with images of what we cant stomachdigestively or culturallyto a more sophisticated understanding of practical and ethical alternatives that make ecological and economic sense. As a farmer and a teacher, I have yet to find a guiding text that does it so well or so comprehensively. Thistlethwaite and Dunlop take us step by step from the open-ended question of breed selection to the finality of slaughter options, providing clear pathways of decision making for farmers, students, consumers, and advocates.

Philip Ackerman-Leist, professor, Green Mountain

College, and author of Rebuilding the Foodshed

To our daughter Fiona

for her patience with this process

and for loving venison backstrap

Foreword

Like the authors of this book, and countless other couples in agriculture, we function as a team. Rather than each of us heading out separately every morning to a distant job, on a typical day we live and labor alongside one another. We share household and ranch chores, take our daily meals together, cooperate in child-rearing duties, and consult with each other about our meat business. Occasionally, we share the speaking stage and sometimes even write collaboratively. When we first met in 2001, Bill was the founder and CEO of Niman Ranch, a collective of hundreds of farmers and ranchers raising livestock using traditional methods, and Nicolette was the senior attorney for an environmental group whose top priority was addressing pollution from the livestock and poultry industries. Both of us, in our very different ways, were fully engaged in what we viewed as the essential task of remaking the norms of how farm animals in the United States and elsewhere would be raised in the twenty-first century.

At the time, more than a decade ago now, concentration, confinement, and concrete had become so widely accepted and entrenched that returning animals to grass seemed more than a monumental task; to many, it seemed an impossibility. Other than animal rights activists, who argued completely against animals in farming, few publicly questioned the appropriateness of the ways in which farm animals were being raised.

The industrialized approach had taken hold gradually. At the dawn of the twentieth century, time-honored husbandry methods were starting to be abandoned. Various human inventions were ushering in the era of mass-scale total confinement systems. One such technology emerged around 1880, when incubators came into widespread use for hatching chicken eggs, especially in Petaluma, California, just up the road from where we now live. A history of poultry farming notes (approvingly) that this set poultry farming on an unerring industrial course. It separated the hen from her eggs and her chicks, usurping the hens brooding and mothering role, and reducing her to nothing more than an egg producer. By 1930, chicken raising had become quite industrialized: Breeds were specialized into egg-laying and meat types (so-called broilers) and a single incubating machine could hatch 52,000 chicks at one time; broiler flocks were kept indoors and numbered in the tens of thousands. In 1938, the DeWitt brothers in Zeeland, Michigan, invented automated feeders for poultry, which substantially reduced the human care required.

Within two years of the United States entering World War II, the government set an annual production goal for chicken meat of four billion pounds, an 18 percent increase over the previous year. Farmers were encouraged to contribute to the war effort by raising defense chicks, which would be raised as food to be shipped abroad to American soldiers and allies. Over these years, the value of domestically raised chickens went from $268 million (in 1940) to over $1 billion (in 1945), nearly a four-fold expansion in just five years.

Novel feed additives soon reinforced the trend toward total confinement. Since the birds were deprived of sunshine, laboratory-manufactured vitamin D had to be included in their feeds. Starting in the early 1950s, antibiotics were added, too. Initially, this was to stave off diseases. Morbidity and mortality had risen sharply as flocks expanded. When poultry farmers first began keeping sizable flocks in confinement, typical rates of death loss quadrupled, jumping from 5 to 20 percent. With commercialization and greater intensification have come [new] disease problems... the chances of disease spread are materially enhanced, two professors of poultry husbandry wrote in the 1930s. Adding antibiotics to daily feed and water reduced rates of death and illness. The continual drug dosing was soon discovered to have the added bonus of dramatically increasing the chickens growth rate as well. By mid-century, some pigs and dairy cows were being kept in large, total-confinement herds.

Next page