More praise for

A PLACE CALLED FREEDOM

Follett skillfully combines tension, eroticism, and an unusual locale.

Detroit Free Press

Follett keeps the pace fast and the writing crisp.

Minneapolis Star Tribune

A richly colored plot Entertaining.

Lexington Herald-Leader

Superb storytelling.

West Coast Review of Books

The action and the tension should keep fans happily turning pages.

Booklist

By Ken Follett: A DANGEROUS FORTUNE

NIGHT OVER WATER

THE PILLARS OF THE EARTH

LIE DOWN WITH LIONS

ON WINGS OF EAGLES

THE MAN FROM ST. PETERSBURG

THE KEY TO REBECCA

TRIPLE

EYE OF THE NEEDLE

A PLACE CALLED FREEDOM*

THE THIRD TWIN*

THE HAMMER OF EDEN*

CODE TO ZERO

JACKDAWS

HORNET FLIGHT *Published by The Random House Publishing Group

This book contains an excerpt from the hardcover edition of The Third Twin by Ken Follett. This excerpt has been set for this edition only and may not reflect the final content of the hardcover edition.

A Fawcett Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

Copyright 1995 by Ken Follett

Excerpt from The Third Twin copyright 1996 by Ken Follett

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Fawcett Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Fawcett is a registered trademark and the Fawcett colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

www.ballantinebooks.com

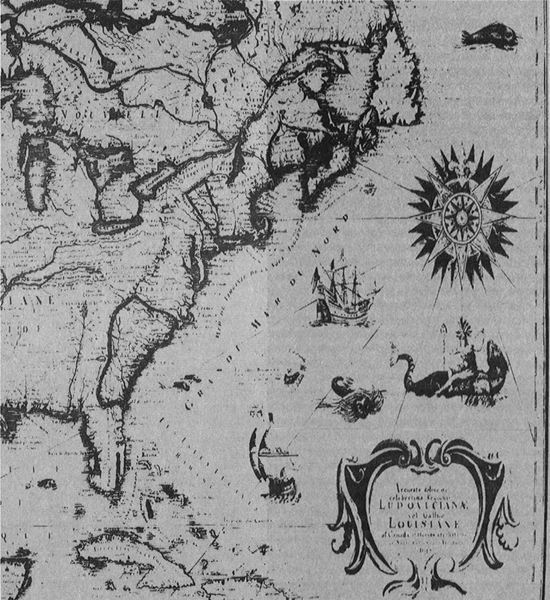

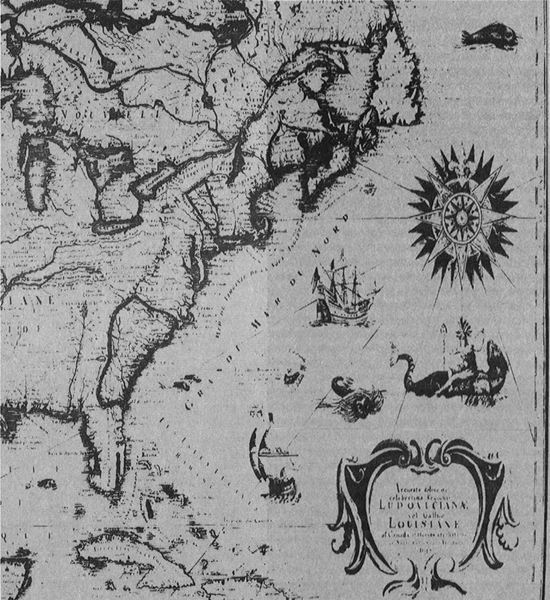

Maps courtesy the Bettmann Archive

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-96170

eISBN: 978-0-307-77519-1

This edition published by arrangement with Crown Publishers, Inc.

v3.1

Dedicated to

the memory of

JOHN SMITH

Contents

I did a lot of gardening when I first moved into High Glen House, and thats how I found the iron collar . The house was falling down and the garden was overgrown. A crazy old lady had lived here for twenty years and never given it a lick of paint. She died and I bought it from her son, who owns the Toyota dealership in Kirkburn, the nearest town, fifty miles away . You might wonder why a person would buy a dilapidated house fifty miles from nowhere. But I just love this valley. There are shy deer in the woods and an eagles nest right at the top of the ridge. Out in the garden I would spend half the time leaning on my spade and staring at the blue-green mountainsides . But I did some digging too. I decided to plant some shrubs around the outhouse. Its not a handsome buildingclapboard walls with no windowsand I wanted to screen it with bushes. While I was digging the trench, I found a box . It wasnt very big, about the size of those cases that contain twelve bottles of good wine. It wasnt fancy either: just plain unvarnished wood held together with rusty nails. I broke it open with the blade of my spade . There were two things inside . One was a big old book. I got quite excited at that: perhaps it was a family Bible, with an intriguing history written on the flyleafthe births, marriages and deaths of people who had lived in my house a hundred years ago. But I was disappointed. When I opened it I found that the pages had turned to pulp. Not a word could be read . The other item was an oilcloth bag. That, too, was rotten, and when I touched it with my gardening gloves it disintegrated. Inside was an iron ring about six inches across. It was tarnished, but the oilcloth bag had prevented it from rusting away . It looked crudely made, probably by a village blacksmith, and at first I thought it might have been part of a cart or a plow. But why had someone wrapped it carefully in oilcloth to preserve it? There was a break in the ring and it had been bent. I began to think of it as a collar that some prisoner had been forced to wear. When the prisoner escaped the ring had been broken with a heavy blacksmiths tool, then bent to get it off . I took it in the house and started to clean it up. It was slow work, so I steeped it in RustAway overnight then tried again in the morning. As I polished it with a rag, an inscription became visible . It was engraved in old-fashioned curly writing, and it took me a while to figure it out, but this is what it said: This man is the property of

Sir George Jamisson of Life

A.D. 1767 Its here on my desk, beside the computer. I use it as a paperweight. I often pick it up and turn it in my hands, rereading that inscription. If the iron collar could talk, I think to myself what kind of story would it tell?

I

Scotland

S NOW CROWNED THE RIDGES OF H IGH G LEN AND LAY on the wooded slopes in pearly patches, like jewelry on the bosom of a green silk dress. In the valley bottom a hasty stream dodged between icy rocks. The bitter wind that howled inland from the North Sea brought flurries of sleet and hail.

Walking to church in the morning the McAsh twins, Malachi and Esther, followed a zigzag trail along the eastern slope of the glen. Malachi, known as Mack, wore a plaid cape and tweed breeches, but his legs were bare below the knee, and his feet, without stockings, froze in his wooden clogs. However, he was young and hot-blooded, and he hardly noticed the cold.

This was not the shortest way to church but High Glen always thrilled him. The high mountainsides, the quiet mysterious woods and the laughing water formed a landscape familiar to his soul. He had watched a pair of eagles raise three sets of nestlings here. Like the eagles, he had stolen the lairds salmon from the teeming stream. And, like the deer, he had hidden in the trees, silent and still, when the gamekeepers came.

The laird was a woman, Lady Hallim, a widow with a daughter. The land on the far side of the mountain belonged to Sir George Jamisson, and it was a different world. Engineers had torn great holes in the mountainsides; manmade hills of slag disfigured the valley; massive wagons loaded with coal plowed the muddy road; and the stream was black with dust. There the twins lived, in a village called Heugh, a long row of low stone houses marching uphill like a staircase.

They were male and female versions of the same image. Both had fair hair blackened by coal dust, and striking pale green eyes. Both were short and broad backed, with strongly muscled arms and legs. Both were opinionated and argumentative.

Arguments were a family tradition. Their father had been an all-round nonconformist, eager to disagree with the government, the church or any other authority. Their mother had worked for Lady Hallim before her marriage, and like many servants she identified with the upper class. One bitter winter, when the pit had closed for a month after an explosion, Father had died of the black spit, the cough that killed so many coal miners; and Mother got pneumonia and followed him within a few weeks. But the arguments went on, usually on Saturday nights in Mrs. Wheighels parlor, the nearest thing to a tavern in the village of Heugh.

The estate workers and the crofters took Mothers view. They said the king was appointed by God, and that was why people had to obey him. The coal miners had heard newer ideas. John Locke and other philosophers said a governments authority could come only from the consent of the people. This theory appealed to Mack.

Few miners in Heugh could read, but Macks mother could, and he had pestered her to teach him. She had taught both her children, ignoring the gibes of her husband, who said she had ideas above her station. At Mrs. Wheighels Mack was called on to read aloud from the Times , the Edinburgh Advertiser , and political journals such as the radical North Briton . The papers were always weeks out of date, sometimes months, but the men and women of the village listened avidly to long speeches reported verbatim, satirical diatribes, and accounts of strikes, protests and riots.

Next page