IN 1964, ASTRONOMERS DETECTED A MYSTERIOUS SOURCE of X-rays in the Milky Way. Subsequent research revealed that the energetic radiation is produced by hot gas, ripped off a giant star by the fierce gravity of an orbiting black hole. In fact, this was the first black hole ever identified in the universe, at a distance of some 6,000 light-years.

The black hole is officially known as Cygnus X-1, which is weird. Cygnus is Latin for swan, but whatever the remote black hole is devouring, it isnt birds. So why would an astronomical object be named after a waterfowl?

Cygnus X-1 is not alone. Some 54 million light-years awaywell beyond our own Milky Way galaxyis a large swarm of other galaxies. It is known as the Virgo Cluster. Virgo is Latin for virginquite a remarkable name for a collection of two thousand or so Milky Ways. Yet another interesting astronomical objecta galaxy emitting radio wavesis catalogued as Centaurus A, but dont expect to find a half man half horse galloping around there.

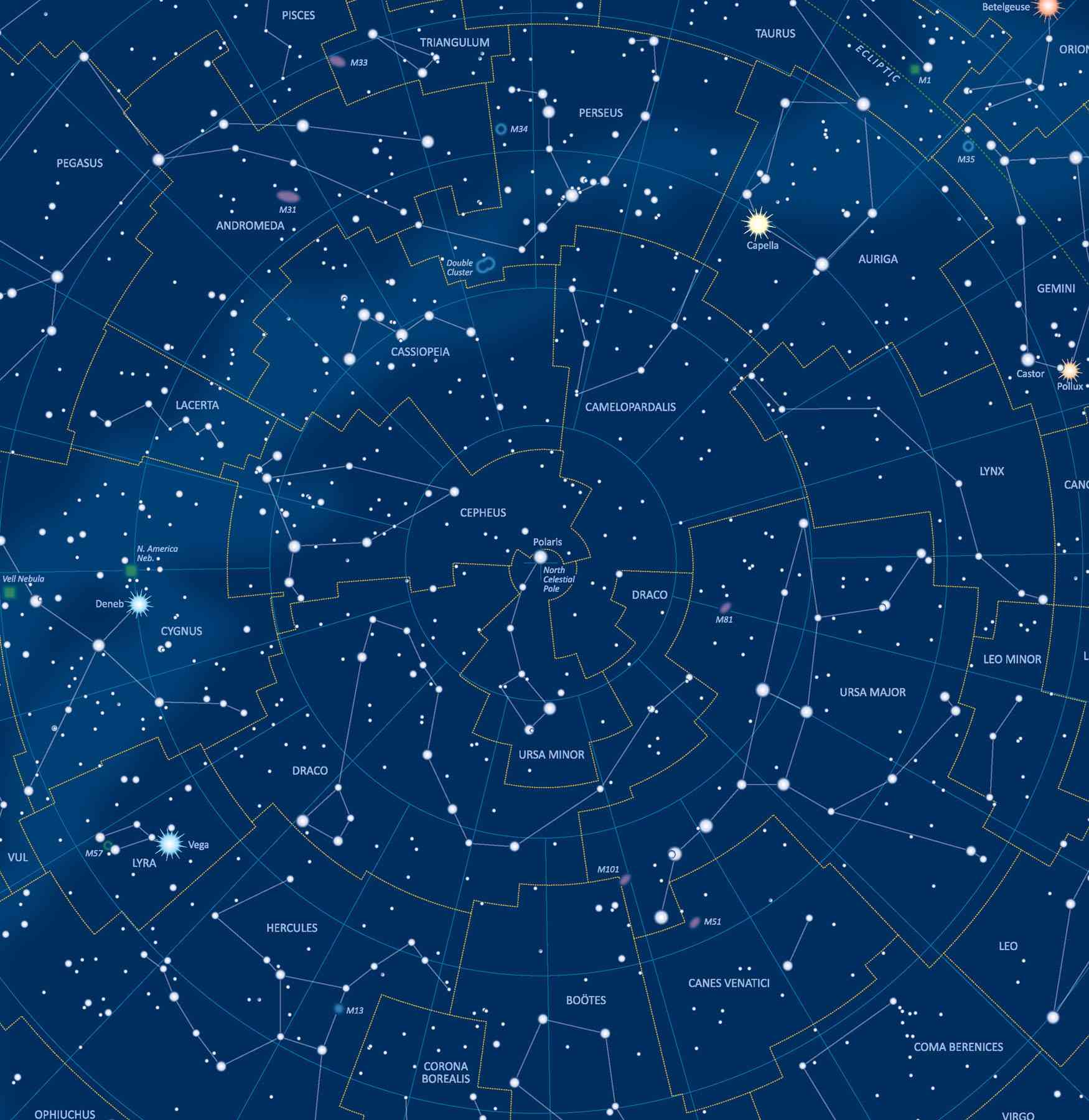

These funny and archaic names, which often show up in contemporary scientific publications like the Astrophysical Journal, refer to the part of the sky in which the objects are located. In prehistoric times, early sky watchers noted a conspicuous group of stars in the northern summer sky that vaguely resembles the shape of a flying swan. Consequently, they called this part of the night sky the Swan, or Cygnus. And since the X-ray-emitting black hole was the first one to be observed in this same area of the night skyin the same constellationit earned the official designation Cygnus X-1. Likewise, the galaxy cluster mentioned above is located in a part of the sky known as Virgo, the Virgin, and the radio galaxy Centaurus A can be found in the constellation that was named after the mythological creature thousands of years ago.

I have always enjoyed the fact that twenty-first-century scientists who study black holes, dark matter, and galaxy collisions still use these age-old names and concepts to denote their objects of research. That Hercules, Orion, and Pegasusnames that were very familiar to the ancientsstill feature on the pages of magazines like Nature Astronomy and Science. It underscores the relation of todays scientists to their predecessors of many centuries ago. After all, just like the Babylonians, Egyptians, and Greeks, we are still trying to make sense of the universe we live in.

Moreover, it reminds us of the fact that every single object in the universe, and everything that happens in space, is observed within the confines of one constellation or the other. In 1054 AD, a star exploded in the constellation Taurus, the Bull. In 1930, Pluto was discovered in the constellation Gemini, the Twins. In 2015, astronomers detected gravitational waves from two colliding neutron stars, 130 million light-years away in a galaxy in Eridanus. And half a century ago, Neil Armstrongs famous giant leap for mankind took place when the moon was in Virgo.

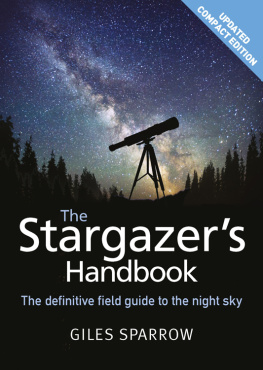

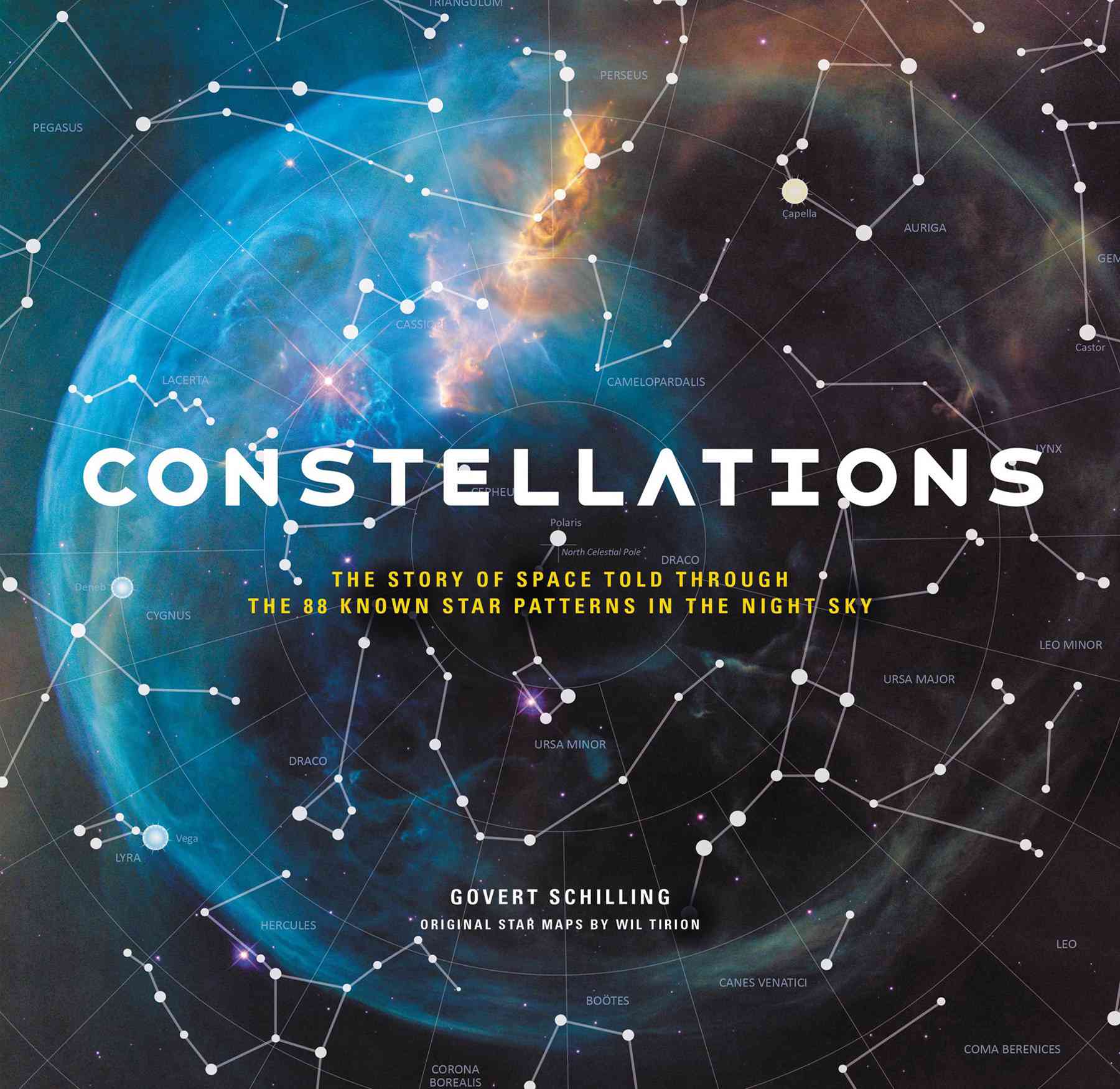

Thus, the eighty-eight constellations of the night sky offer eighty-eight windows on the entire universe and on the history of astronomy. Each new insight in the contents and evolution of the cosmos was gained by astronomers training their instruments to a particular point on the sky, and every spacecraft encounter, comet discovery, or Mars landing took place within the borders of one of the eighty-eight constellations.

Often enough, astronomy websites and newspaper stories report on exciting new discoveries and events, like an extremely remote galaxy at the edge of the observable universe, a monstrous black hole, or a space probe flyby of a distant planet. This book uniquely ties all these finds and occurrences, both historical and more recent, to the constellation in which they happened.

My hope is that after you read and browse through this book, the night sky will never be the same again. Right above your head, in familiar constellations like Orion or Scorpius, or in obscure ones like Camelopardalis and Norma, is where the science of astronomy has matured and where milestone discoveries in the study of the universe have played themselves out.

I thank the team at Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers for their confidence in this exciting project, and I am honored that world-famous astrocartographer (and fellow Dutchman) Wil Tirion was willing to draw the beautiful constellation maps, which have been specially designed and adapted for this book. Most of all, however, I have to thank the astronomers of the past and the present for their perseverance in studying the wider universe we are all part of, and for presenting us with a wealth of mind-boggling discoveries and breathtaking images.

GOVERT SCHILLING

This map from a 1795 star atlas shows the now-obsolete constellations Antinous (center) and Taurus Poniatovii (Poniatowskis Bull, right).

ON THE AFRICAN SAVANNAH, hundreds of thousands of years ago, early hominids must have marveled at the night sky. No one could fathom the true nature of the stars, but seeing the same patterns slowly revolving around the Earth night after night and year afte r year must surely have fired the imagination. No doubt that the most conspicuous of these patterns received names as soon as