Contents

Our planet is surrounded by a Universe that stretches for billions of light years in every direction. Wherever we look, stars, gas and dust clouds, and distant galaxies are scattered more or less at random across space. For thousands of years, constellations have played a key role in helping us make sense of this apparent chaos.

Todays system of 88 constellations has evolved since prehistoric times: the earliest depiction of Taurus, the Bull, comes from a 17,000-year-old painting at Lascaux, France. The first lists of constellations ancestral to our own were compiled in ancient Mesopotamia more than 4,000 years ago.

Probably the earliest constellations to be recognized were those of the zodiaca group of a dozen star patterns traditionally attributed special significance because the Suns annual path around the sky passes through them. The word zodiac comes from a Greek term meaning circle of animals, and indeed all but one of these 12 constellations represents a living creature. The exception, Libra, was once part of neighboring Scorpius. Thanks to the almost flat alignment of their orbits around the Sun, the planets are also usually found within these constellationsthe idea that the positions of these wandering celestial bodies in the zodiac had some relationship to events on Earth dates back to at least the first millennium BC , and survives in the persistent fascination of astrology. Thanks to long-term cycles of change in Earths axis of rotation, however, the Suns present path across the sky is largely out of step with the astrological zodiac.

While different cultures around the world developed their own star patterns at different points in history, and many of these are still in local use, astronomers today use a standardized list developed from the work of the Greek-Egyptian astronomer and geographer Ptolemy of Alexandria. Around AD 150, Ptolemy summarized the astronomical knowledge of the classical world in a great work known as the Almagest. Ptolemys list of 48 constellations includes all of the ancient zodiac signs, and most of the others still recognized in northern and equatorial skiesit survived unaltered for around 1,400 years.

It was only from the 16th century that European explorers returned the first details of the far southern stars. Astronomers soon began to introduce these discoveries into their charts, often making further additions to northern skies at the same time. A dozen new constellations were added to the southern sky by the followers of Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman around 1600. However, large areas of the sky remained forsaken until the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille invented a further 14 constellations for his great survey of the southern stars, published in 1763.

Finally, between 1922 and 1930, the International Astronomical Union agreed a list of 88 constellations, each formally defined as an area of the sky rather than a group of stars. Together, these 88 encompass the entire celestial sphere, ensuring that every object in the sky now belongs to one constellation or another.

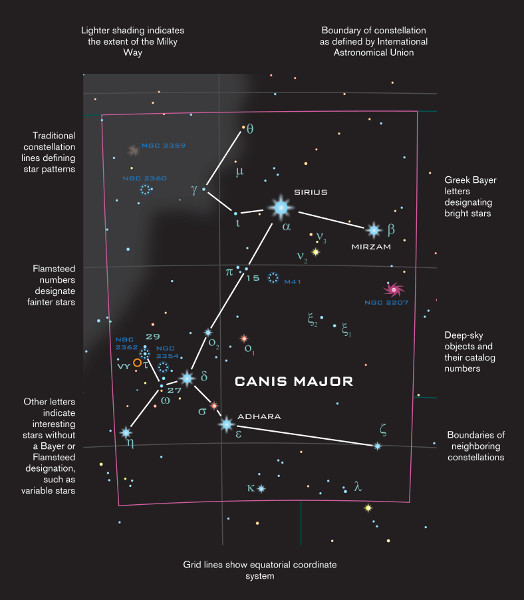

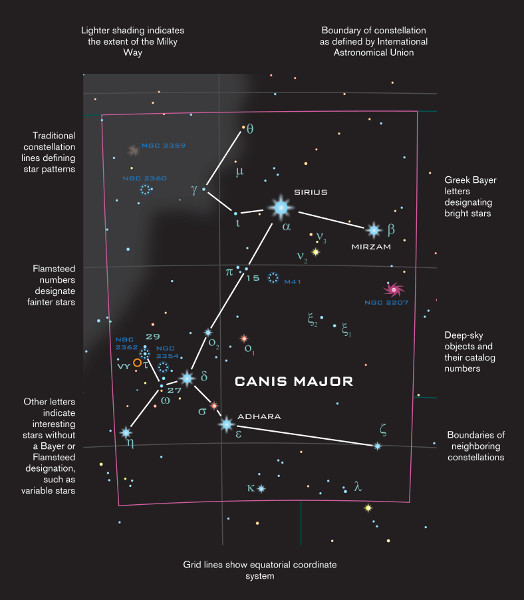

Within the constellations, astronomers have ordered stars in various ways. Traditionally, Greek letters are used to indicate the brightest stars, according to the system devised by German astronomer Johann Bayer in 1603. Fainter stars are often assigned Flamsteed numbers (introduced by English astronomer John Flamsteed in the early 18th century), while unusual stars and other celestial objects (often collectively known as deep-sky objects) bear numbers or letters from a variety of other systems.

The brightness of stars is measured by their apparent magnitudethe brighter a star appears, the lower its magnitude number. This system originated in ancient Greece, but was formalized in the 19th century: today a difference of one magnitude between stars indicates that one star is roughly 2.5 times brighter than the other. The brightest stars have negative magnitudes, and the faintest naked-eye stars are around magnitude 6.0. On the maps used in this book, stars of different sizes are used to represent different brightnessesmore information about interpreting the maps is supplied overleaf.

This book offers a comprehensive introduction to understanding the individual constellations, and the night sky. The describe how our location on Earth affects our view of the Universe, and how astronomers impose an ordered system of coordinates and constellations onto the sky. The main section of the book then takes us on a journey through the 88 officially recognized star patterns, describing the wonders that lie within them that can be seen with the naked eye, binoculars, or relatively modest amateur telescopes.

The constellations were the first tools of astronomy, and still offer an important means of ordering the cosmos. Even today, an ability to recognize these celestial patterns and a knowledge of their bright stars and significant objects is a vital tool in the arsenal of any amateur stargazer. Only learn to understand the constellations, and the entire book of the Universe will open up before you.

On the maps used throughout the book, stars of different sizes are used to represent different brightnesses. The color of stars on the maps represents their actual measured colors, usually indicative of their surface temperature.

The brightness of stars is measured according to a system known as magnitude, formalized in 1850 by the English astronomer Norman Robert Pogson. According to his scheme, the lower a stars magnitude number, the brighter it is. The key shown here represents the scales of stars used in the large individual maps.

On the individual maps, nonstellar deep-sky objects are also represented using the special symbols shown in the lower key. While the stars shown on the maps should all be visible to the naked-eye under dark skies, most of the deep-sky objects will require either binoculars or a small telescope.

The Greek alphabet

The brightest stars in each constellation are represented by a system of Greek Bayer letters, in accordance with the Greek alphabet as shown here. However, the system has many inconsistencies, with some stars bearing the wrong letters due to a variety of historical accidents. Fainter stars down to the limits of naked-eye visibility are often given Flamsteed numbers, linked to their location within the particular constellation.

alpha |

beta |

gamma |

delta |

epsilon |

zeta |

eta |

theta |

iota |

|

Next page