CAPTURING

THE STARS

Astrophotography

by the Masters

Robert Gendler

Foreword by Neil deGrasse Tyson

The stellar nursery NGC 6188 has formed generations of young, vibrant stars and iridescent nebulae. Robert Gendler and Martin Pugh

The interlocking giant shells and hollow cavities of the Tarantula Nebula are believed to have formed from generations of powerful stars and their supernovae. Robert Gendler

The Big Dipper comprises the seven brightest stars of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. Bill and Sally Fletcher

Abell S0740 is a dazzling assortment of galactic specimens 450 million light years distant. Lisa Frattare and Zolt Levay

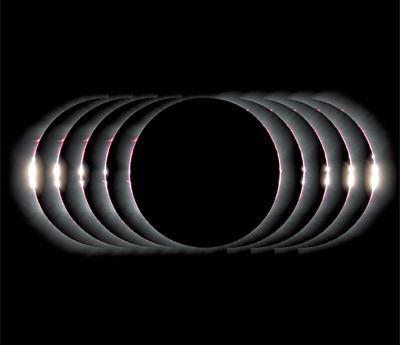

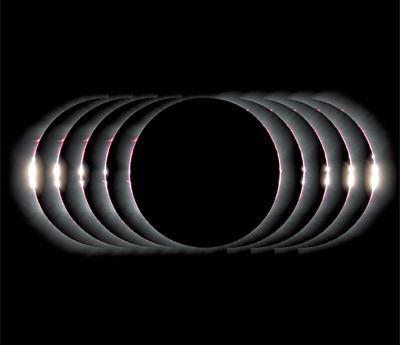

The phenomenon Bailys Beads is exhibited during the total solar eclipse of 2006. Fred Espenak

A core of massive stars illuminate the Trifid Nebula (M20). Johannes Schedler

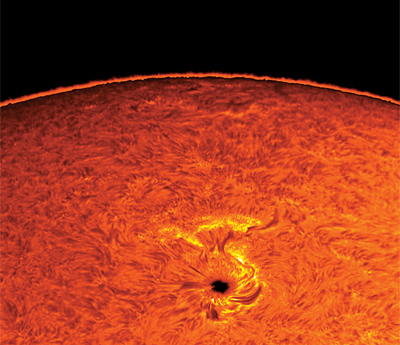

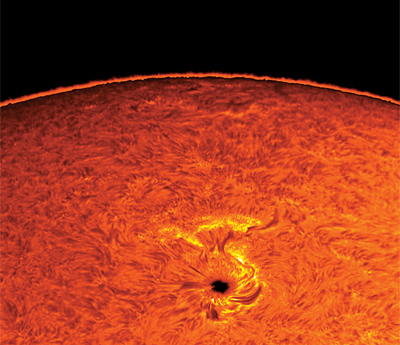

Although Sunspot 898 appears small against the suns disk, its size approaches that of the planet Neptune. Greg Piepol

The Large Magellanic Cloud is a nearby dwarf galaxy named for the explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who noted its presence in 1519. Robert Gendler

Whirlpool Galaxy. Lisa Frattare and Zolt Levay

Back cover

IC 1274. Jean-Charles Cuillandre and Giovanni Anselmi

TO ALL PHOTOGRAPHERS PAST AND PRESENT

WHO HAVE ASPIRED TO CAPTURE

AN EXTRAORDINARY MOMENT IN TIME.

TO MY FATHER, A PHOTOGRAPHER BY PROFESSION,

WHO BY NATURE AND NURTURE HAS SHAPED MY PASSION.

R. G.

THERE IS NO END.

THERE IS NO BEGINNING.

THERE IS ONLY THE PASSION OF LIFE.

FEDERICO FELLINI

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON

IN ASTROPHOTOGRAPHY, unlike all other branches of this noble art, the cosmic photographer does not get to illuminate the subject or tell the subject to stand a different way to improve the angle of view. The sky above is just there. The objects in it are just there. Not only that, the extreme light travel time from the depths of the universe to Earth forces the photographer to view most objects not as they are but as they once were, long ago. Beyond these profound limitations, one might be further surprised to learn that the most interesting objects in the universe are so dim that the photographer does not even see in advance what the picture will become when fully exposed. Astrophotography might then be the humblest of hobbies, even while its subject draws from the most beautiful vistas there ever were.

In modern times we have no shortage of beautiful cosmic images from celebrated professional sources, such as the Hubble Space Telescope. So why turn to an atlas chock full of images taken not just by professionals but by amateur astronomers with their personal cameras from their suburban backyards? First, the era of affordable digital detectors greatly reduces the relative advantage that a professional telescope formerly had over amateur equipment. Second, the field of view of professional telescopes is generally quite small. The Hubble, for example, sees no more of the night sky than 1/100 the area of the full moon. Meanwhile, an amateur setup using a simple camera, or a camera combined with a moderate-sized telescope, can capture large swaths of skyin some cases, entire constellationsrevealing dim but large-scale features within our own Milky Way that would otherwise lay undiscovered in front of our noses.

As we have known for some time, Earth rotates continuously. As these large-scale features drift by, any attempt to expose an image for more than a few seconds blurs the stars and other light-emitting objects, just as would a time lapse of car headlights along a highway. To avoid this, one must somehow compensate precisely for Earths rotation. Of course, the clock drive was invented long ago to solve just this problem. Some clock drives even allow you to make adjustments to follow objects, such as comets, that are themselves in motion against the drifting background sky. In all cases, the sharpness of a final image depends heavily on how well the clock drive works, especially for the longest of exposures one may require.

The camera and telescope combo operates like a light bucket. In a fraction-of-a-second exposure, such as what the brain does with human vision, you can detect only so much light. But with full control over exposure time, combined with the highly sensitive digital detectors used in modern cameras, you can fill your bucket with as much light as you likeexposing the scene for as long as you have the patience to support and as long as you trust the stability of your clock drive. A single image can take several minutes to expose. Others can take several hours; still others, the most challenging targets of the night sky, may require many nights of work.

With each added moment of exposure, the gossamer, ghostlike features of a nebula or a galaxy become brighter, more delineated, more revealed. Like the sculptor in Pygmalion, where each strike of the hammer and chisel brings the subject closer and closer to life, the astrophotographer exposes the detector until the subject rises from the depths of space to become a work of art unto itself. And whether or not the nebula or galaxy comes to life, whats certain is that, as in Pygmalion, the astrophotographer falls in love with the images themselves.

In this case, Robert Gendlers Capturing the Stars cannot be read and viewed without feeling that these committed photographers are smitten by the universe and hopelessly enchanted by the objects it contains, while inviting the reader to be similarly taken by their splendor.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, though a professional astrophysicist for more than two decades, continues to count himself among the ranks of amateur astronomersan association he has held since the age of twelve, when he took his first photographs of the night sky. Tyson is director of New York Citys Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History and is the author of nine books on the universe, most recently Death by Black Hole: And Other Cosmic Quandaries and The Pluto Files: The Rise and Fall of Americas Favorite Planet.

PREFACE

THE CORE OF THIS BOOK relates to astrophotographers and their art. The essence of this photographic compilation is to bring to print the most provocative and visually compelling portraits of the deep sky and of local astronomical phenomena taken by the worlds most accomplished astro-photographers. The modern astrophotographic process can be broken down into the technical and the artistic. The technical aspect is substantial and requires technical precision and refinement of the highest order. It is beyond the scope of this book to list the numerous technical innovators who were so vital to establishing the enormously sophisticated state of modern astronomical imaging that we enjoy today. That said, in a few cases the successful practitioners and technical innovators were one and the same.

Next page