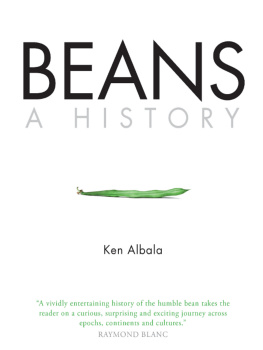

BEANS

BEANS

A History

Ken Albala

English edition

First published in 2007 by

Berg

Editorial offices:

First Floor, Angel Court, 81 St Clements Street, Oxford OX4 1AW, UK

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

Ken Albala 2007

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form

or by any means without the written permission of

Berg.

Berg is the imprint of Oxford International Publishers Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Albala, Ken, 1964

Beans : a history / Ken Albala. English ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-8578-5078-2

1. LegumesHistory. 2. BeansHistory. I. Title.

QK495.L52A567 2007

641.3'565dc22

2007015769

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JS Typesetting Ltd, Porthcawl, Mid Glamorgan.

Printed in the United Kingdom by Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn.

www.bergpublishers.com

Contents

When I first proposed a history of beans, little did I suspect what I was getting myself into. To truly understand beans, to become one with my subject, I resolved to eat beans every single day, ideally a new species or variety with every meal. Soon my cabinets were bulging with heirloom appaloosas, delicate Spanish Tolosanos, football-shaped lablabs, specimens from the far-flung corners of the globe, from tiny teparies to mammoth Greek gigantes. There followed regular visits to ethnic grocery stores, especially Indian for every form of dhal, hours spent hulling and peeling fresh favas, and frenzied Internet bean forays in the middle of the night. I munched pickled lupines for breakfast, snacked on Japanese wasabi peas, frightened the children with sticky natto, and with nearly every supper I pulled out the brimming bean pot. Chickpea flour panisses, South Indian dhosas, African bean fritters followed suit. There was always a bowl or two of beans soaking with zen-like patience on the countertop. I made it about a year before giving up. I still try a new bean every week or so, but I am happy to say, my system is relieved to be done with this prolonged and sometimes grueling experiment. No matter what anyone says, tolerance for the bean and its gaseous effects does not develop over time. You just get used to bloat. At least I can say I am full of beans.

When I first proposed a history of beans, little did I suspect what I was getting myself into. To truly understand beans, to become one with my subject, I resolved to eat beans every single day, ideally a new species or variety with every meal. Soon my cabinets were bulging with heirloom appaloosas, delicate Spanish Tolosanos, football-shaped lablabs, specimens from the far-flung corners of the globe, from tiny teparies to mammoth Greek gigantes. There followed regular visits to ethnic grocery stores, especially Indian for every form of dhal, hours spent hulling and peeling fresh favas, and frenzied Internet bean forays in the middle of the night. I munched pickled lupines for breakfast, snacked on Japanese wasabi peas, frightened the children with sticky natto, and with nearly every supper I pulled out the brimming bean pot. Chickpea flour panisses, South Indian dhosas, African bean fritters followed suit. There was always a bowl or two of beans soaking with zen-like patience on the countertop. I made it about a year before giving up. I still try a new bean every week or so, but I am happy to say, my system is relieved to be done with this prolonged and sometimes grueling experiment. No matter what anyone says, tolerance for the bean and its gaseous effects does not develop over time. You just get used to bloat. At least I can say I am full of beans.

This project also proved to be a challenge in other ways as well. My interest in the topic was initially sparked by the overwhelming prejudice against beans in European dietary literature. This was clearly a class-based antagonism only rustics and laborers have stomachs powerful enough to digest beans, pundits claimed. I wondered if there were similar prejudices in other times and places. Are beans always considered peasant food, and if not, why? My research, covering every corner of the globe from prehistoric times to the present and traversing a staggering array of disciplines, yielded something fascinating and new nearly every day. Beans are truly an amazing topic. There was a single-subject food book left to be written after all, and for some reason undaunted by the scale and depth of the project, I jumped in.

Readers will notice immediately that I have an inexplicable weakness for botanical Latin. Just the sound of some names thrills me. Even before I studied the language, I would memorize the most bizarre terms Lycopersicon esculentum, the edible wolf peach, alias tomato. I use these Latin terms here not be pedantic, but because names, in whatever language, reveal history and attitudes toward plants. I dont claim to be knowledgeable about botany, and I am a pretty mediocre gardener, but plants do have an irresistible charm, and as I have found, every species in the family Fabaceae has its own unique allure. It was for this reason that I decided to organize this book as a series of bean biographies, with each chapter focusing on an individual or group of related beans.

Although this book is written for a popular audience, I would like to point out that every source I have used is listed in the bibliography and for those of you who have access to primary sources or wish to read the secondary ones, it will be easy to figure out the exact pages from which I have drawn quotes and citations, though space limitations have prevented me from being able to offer footnotes. I would be more than happy to direct any reader to a specific source page or answer any query if you contact me via e-mail at kalbala@pacific.edu. Many of the sources, particularly old cookbooks, are also available online, and can be found easily using any search engine.

This book would also not have been possible to write without all the enormous help I have been given along the way. It never ceases to amaze me how kind and generous people can be, especially with such an odd topic as beans. Jinx Staneic collected stories from West Virginia and scrounged up pinquito beans for me. Linda Berzok sent me teparies from Arizona. Mary Margaret Pack hunted down lyrics. Alice McLean shared with me some black chickpeas from the very last garden tended by Patience Gray. Barbara Wheaton made me a list of old cookbooks with bean recipes among other invaluable favors. Gary Allen, the cannibal, clarified a Hannibal Lecter reference. Janet Chrzan sniffed out zolfino beans in Tuscany before my own trip last summer. Andy Smith answered any question at any time of day or night, in meticulous detail. Darryl Corti pointed out some obscure beans for sale at his store in Sacramento. Robert Merrett gave me a wonderful lentil passage from George Gissing. Some very pleasant farmers were kind enough to chat at the Tracy Dry Bean festival I still have a few cups left of the many sacks I bought. Mark Brunell enlightened me on the wonders of leghemoglobin. Shawn Chavis lent me her notes on black-eyed peas. Kara Neilsen cooked Scappis chickpea zeppole. Many people at the Stockton Certified Farmers Market sold me some magnificent fresh favas, chickpeas and pigeon peas, as did my favorite grocery in town, Podestos. What I would do without my regular fix of lupines, I cannot guess. Gregg Camfield chortled over Thoreau with me. Rachel Laudan led me down a fascinating path on medieval bean consumption. Jeff Charles sent me a copy of a dreadful lima bean cookbook from the early twentieth century. Mel Thomas, my old Latin pal, from the other end of the continent rescued me from translating blunders in Valerianos bean poem. Mary Gunderson offered details about Lewis and Clark. Paul B. Thomson after meeting just briefly via e-mail sent me a copy of his book. Adam Balic shared with me the wonders of carlin peas and John Letts let me see some that were left on Baffin Island by Martin Frobisher. And so many other people via e-mail gave me ideas and comments, my thanks especially to friends on the ASFS listserve who for a few steady weeks issued a barrage of bean references.

I must also thank my college, the first chartered institution of higher learning in the state of California, the University of the Pacific, for funding several research and conference trips to Europe, all of which directly contributed to the writing of this book, and all of which proved to be great eating adventures. I am also grateful for a sabbatical to write this book, and to my colleagues in the history department who as usual prove to be great friends. Thanks to the wonderfully helpful people at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe, where I began research for this book. Thanks also to the Culinary Trust, philanthropic partner of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, for awarding me the Linda Russo grant to conduct the final stages of research at the Clements Library at the University of Michigan. Special thanks to all the wonderful people I met there Phil, Barbara, Oxana, Valerie, Laura, Don and especially Jan Longone, who brought me sources from home and literally just dropped them into my lap.

Next page

When I first proposed a history of beans, little did I suspect what I was getting myself into. To truly understand beans, to become one with my subject, I resolved to eat beans every single day, ideally a new species or variety with every meal. Soon my cabinets were bulging with heirloom appaloosas, delicate Spanish Tolosanos, football-shaped lablabs, specimens from the far-flung corners of the globe, from tiny teparies to mammoth Greek gigantes. There followed regular visits to ethnic grocery stores, especially Indian for every form of dhal, hours spent hulling and peeling fresh favas, and frenzied Internet bean forays in the middle of the night. I munched pickled lupines for breakfast, snacked on Japanese wasabi peas, frightened the children with sticky natto, and with nearly every supper I pulled out the brimming bean pot. Chickpea flour panisses, South Indian dhosas, African bean fritters followed suit. There was always a bowl or two of beans soaking with zen-like patience on the countertop. I made it about a year before giving up. I still try a new bean every week or so, but I am happy to say, my system is relieved to be done with this prolonged and sometimes grueling experiment. No matter what anyone says, tolerance for the bean and its gaseous effects does not develop over time. You just get used to bloat. At least I can say I am full of beans.

When I first proposed a history of beans, little did I suspect what I was getting myself into. To truly understand beans, to become one with my subject, I resolved to eat beans every single day, ideally a new species or variety with every meal. Soon my cabinets were bulging with heirloom appaloosas, delicate Spanish Tolosanos, football-shaped lablabs, specimens from the far-flung corners of the globe, from tiny teparies to mammoth Greek gigantes. There followed regular visits to ethnic grocery stores, especially Indian for every form of dhal, hours spent hulling and peeling fresh favas, and frenzied Internet bean forays in the middle of the night. I munched pickled lupines for breakfast, snacked on Japanese wasabi peas, frightened the children with sticky natto, and with nearly every supper I pulled out the brimming bean pot. Chickpea flour panisses, South Indian dhosas, African bean fritters followed suit. There was always a bowl or two of beans soaking with zen-like patience on the countertop. I made it about a year before giving up. I still try a new bean every week or so, but I am happy to say, my system is relieved to be done with this prolonged and sometimes grueling experiment. No matter what anyone says, tolerance for the bean and its gaseous effects does not develop over time. You just get used to bloat. At least I can say I am full of beans.