Copyright 2016 by Drew Campbell

All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Allworth Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Allworth Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Allworth Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

20 19 18 17 16 7 6 5 4 3

Published by Allworth Press, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Allworth Press is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.allworth.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Print ISBN: 978-1-62153-542-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62153-544-7

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

For Lucas, who taught me to love it.

Foreword to the Third Edition

A few minutes ago, I used my phone to send Tad Crawford, the long-suffering publisher of Technical Theater for Nontechnical People, an update about the manuscript for the third edition. I keep the document online in a cloud so I can access it on my phone, tablet, laptop, and desktop computers. My phone also has applications for video editing, show audio playback, calculating lumber requirements, and translating theatrical terms into Chinese.

When the first edition of this book went to press in 1996, I didnt even have a pager. When the second edition came out in 2004, my cell phone made phone calls. Sometimes.

Times change.

Then again, some things stay the same.

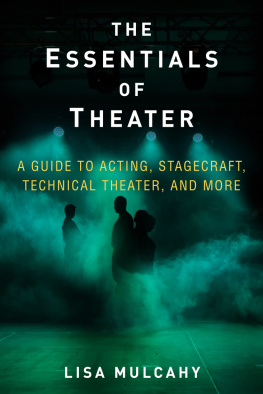

I wrote the original version of this book for people who want to know how things worked backstage without getting into the gritty details, the people whom Apple famously named the rest of us, the ones who want to use computers, not program them. These people dont really want to hang lights or build platforms. They just want to talk to lighting designers and survive tech rehearsal. The original title of the book, in fact, was Backstage Survival .

In the nineteen years that this book has been around, nothing has gotten less complicated. Machines have not gotten simpler. Options have not decreased. The influx of digital gear has not reduced the workload, eliminated jobs, or simplified our lives, despite the clean, organized future that George Jetson lives in. Rather, the massive increase in technology has done the same thing for the theater that it did for the film industry, the corporate office, the Mexican vacation, and the dinner date. It has allowed us to do more in the same amount of time.

And yet, the important things havent changed. There are still people who want to be technicians and people who dont. There are stillGod love empeople who want to see a show and be entertained. And theater people, technical and otherwise, still show up at the stage door for the same reason they always didto tell that audience a story.

So, I said it nineteen years ago and Ill say it again: if you want to be a professional theatrical technician, then flip to the appendix and choose from the vast library of books with detailed information on all things technical.

If, however, you want to act, dance, sing, direct, produce, manage, preach, model, compete, run a meeting, give an award, sing Happy Birthday, make a dove disappear, or stand on any stage, anywhere, for any reason at all, then this book is for you. Its a jungle backstage, but have courage. By the time we are through, the trees will look like trees, the monkeys will howl on cue, the moonlight will filter mysteriously through the leaves, and all those technical tigers will be rugs in front of your simulated fireplace.

General Notes

A Note About Gender

One of the as-yet-unsolved problems in the English language is the absence of a gender-neutral, third-person singular pronoun. Unlike the French, who have the delightfully pragmatic use of the pronoun on, we must struggle along with only he and she and all their related forms (his, hers, himself, herself, and so on). The closest approximationonehas a cold, businesslike quality to it, and, personally, I find using his or her a bit awkward. Therefore, I have decided simply to alternate between the masculine and feminine forms. While you are reading, you may encounter generic technicians or designers who have assumed one sex or the other. Please do not interpret this to mean that any job is limited to only half of our population. I am often heartened that jobs in the theater business tend to be less gender-specific than those in other industries. The word actor seems to have become a neutral word for both sexes, however, so I will stick to that rather than alternating with actress.

Highlighted Words

As you are reading, you will notice that many terms appear in boldface type. This is to indicate a term that you really should know to survive backstage. All terms in boldface appear in the glossary at the end of the book.

CHAPTER 1

Breaking It Down: Who Does What

T heater is collaborative. We never do it alone. Theres no such thing as a one-man show. Being backstage means being surrounded by peoplepeople who assume a wide variety of titles and responsibilities. As a show person, you do not need to know how to do all their jobs. You do not have time to do all their jobs. You need to know who to talk to when the carpet is coming up behind the podium, or the work light backstage is burned out, or the Frosty the Snowman costume is ripping open. Scenic designers, prop coordinators, stage managers, tech directors, first hands, flymenthey surround you at every turn, and, if they are any good, they are there to help you. So who are all these people? And who can help you staple down that carpet?

Not an easy question. There are constant overlaps between areas of responsibility, and many things must be worked out case-by-case. Sometimes a simple task requires input from several departments. Consider this example: The script calls for a lamp to be sitting on a table. The scenic designer talks to the director and decides what the lamp should look like. Then the designer shows the design to the propmaster , who either buys the item, pulls it from stock, or builds it. The finished lamp is brought to the stage, where the electrician wires it up. The lighting designer decides how big of a bulb to put in it and when it should be on (with more input from the director). The lighting designer then communicates that information to the dimmerboard operator who, under the direction of the stage manager , operates the light during the show. If the light has to move during a scene change, that task is the responsibility of the stage crew chief . One objecteight people. Hard to believe we get anything done at all.

Talking to the wrong person, however, can gum up the works pretty good. Consider poor, hapless director Steve, who tells the dimmerboard operator to turn the lamp on later than he did last night, thereby circumventing normal procedure and causing the following headset conversation:

Stage Manager: Light Cue 49 go.

Dimmerboard Operator: No, not yet.

SM: What?