Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

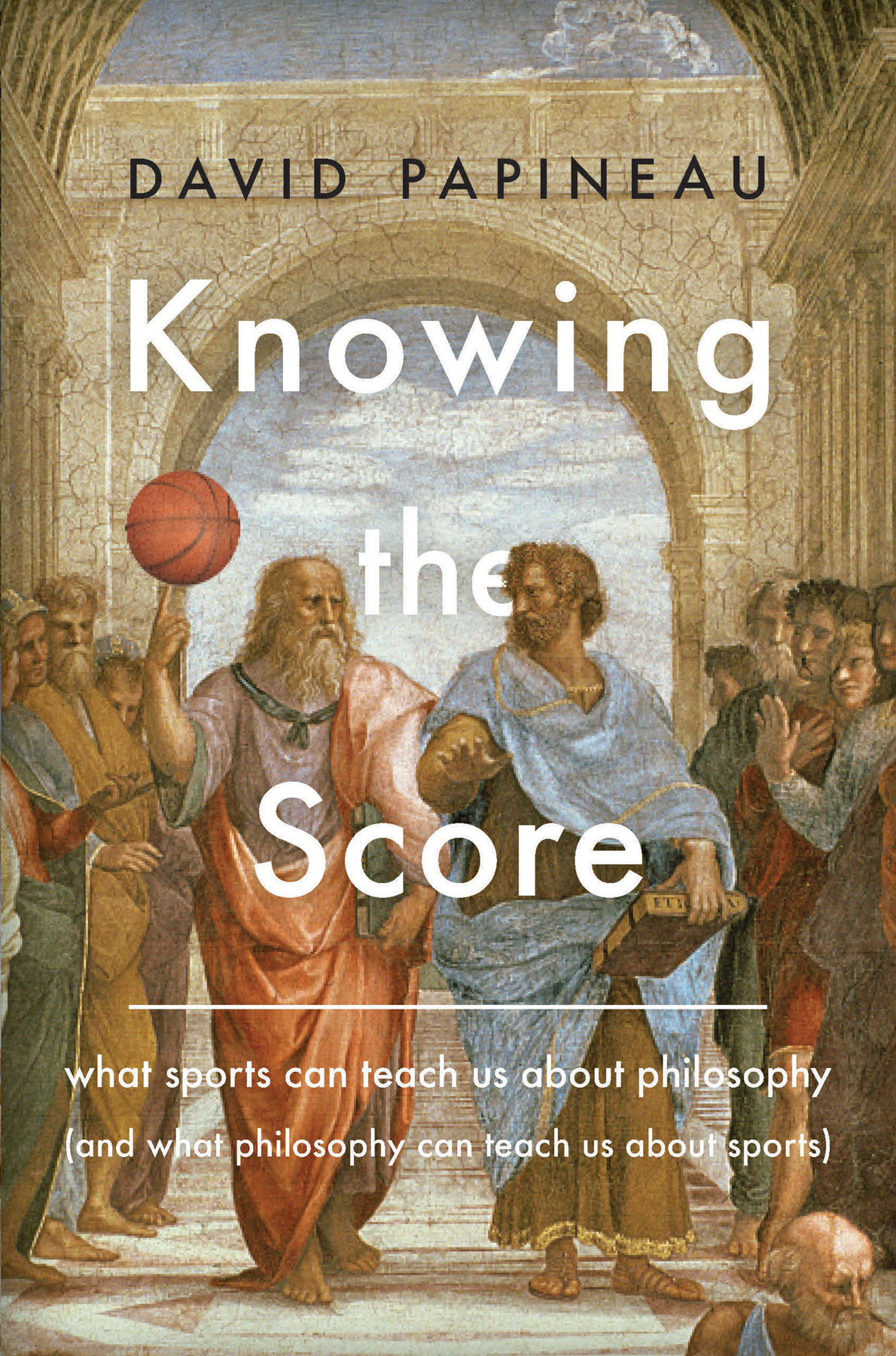

Names: Papineau, David, 1947 author.

Title: Knowing the score : what sports can teach us about philosophy (and what philosophy can teach us about sports) / David Papineau.

Description: 1 | New York, NY : Basic Books, 2017.

Subjects: LCSH: SportsPhilosophy. | Philosophy. | BISAC: SPORTS &RECREATION / Sociology of Sports. | SPORTS & RECREATION / Sports Psychology.

S OMETIMES I WISH I had been more of an athlete and less of a philosopher.

I have worked most of my adult life as an academic philosopher. I have written several books and many articles. A number of learned societies have elected me their president. And I am still employed as a professor, in two well-known philosophy departments, in London and New York.

My sporting career has been rather less distinguished. This hasnt been for lack of trying. I have competed at tennis, soccer, golf, cricket, rugby, squash, field hockey, and sailing. And thats not just in high schoolI have played organized versions of all these sports as an adult, not to mention recreational fishing, sailboarding, and bodysurfing.

My enthusiasm, however, has always outstripped my success. Its not that Im a duffer, but I have never risen above the lower echelons. I have scored centuries at cricketbut most were for teams of journalists playing village sides. In my time I was a force to be reckoned with in the fourth division of the North Middlesex Tennis League. I am still competitive off my golf handicap of 17. You get the idea.

Perhaps I wouldnt have enjoyed life as a serious sportsman, even if my abilities had allowed it. One of the themes that will emerge in these pages is that top-level sports demand a peculiar mind-set, a blinkered focus on physical routine. Its not clear that its a natural life for someone with philosophical inclinations. Still, this hasnt stopped me spending a large proportion of my waking hours playing, watching, and thinking about sports, rather than working at my day job.

Until recently, it never occurred to me to combine my two enthusiasms. There is an area of my subject that goes under the heading philosophy of sport. But it has never excited me. Central topics are the ethics of drug use, sport and politics, disability and enhancement, the definition and value of sport, and so on. The normal strategy is to take some contentious topic that exercises sports practitioners or administrators, and then analyse the solutions implied by different philosophical theories. It is all a bit earnest, as if the writers want to counterbalance their frivolous subject matter with the sobriety of their prose. I have always kept away. I enjoy sports, and this seemed to make it dull.

Then, a few years ago, Anthony OHear, Director of the Royal Institute of Philosophy, asked me to contribute to a lecture series he was organizing on Philosophy and Sport. It was the year of the London Olympics, and he thought it would be a good idea to devote the Institutes annual programme of lectures to the subject. I couldnt really refuse. I agreed it was a good idea, I was on the Council of the Institute, and I had an extensive knowledge of both philosophy and sport. If I wasnt going to say yes, who would?

So I set to work. I read some of the philosophy of sport literature, and started sketching out some thoughts about the definition and significance of sport. But nothing much happened. I couldnt get beyond the most obvious truisms, and was starting to have bad dreams about finding myself in front of the audience with nothing to say.

After struggling for a while, I made a decision. Instead of writing about one of the topics that philosophers of sport are supposed to write about, I resolved to write about something that interested me. If it didnt count as philosophy of sport, that would just be too bad.

The topic I chose was the peculiar mental demands of fast-response sports like tennis, baseball, and cricket. When tennis star Rafael Nadal faces Roger Federers serve, he has less than half a second to react. Thats scarcely enough time to see the ball, let alone think about how to hit it. Nadal can only be relying on automatic reflexes. Yet at the same time his shot selection also depends on his consciously chosen strategy, on that days plan for how best to play Federer in those conditions. This struck me as puzzling. How can unthinking reflexes be controlled by conscious thought?

I had great fun addressing this conundrum in my lecture. I didnt try to hide my enthusiasm as a sports fan, and I included as many anecdotes as seemed relevant. But I also ended up with a series of substantial philosophical conclusions. Even though I started with nothing but a few sporting incidents and some everyday questions, I was led to think hard about the connection between conscious decision-making and automatic behaviour, and the result was a series of ideas about the structure of action control that has opened up a new area of research for me. (If you want to read a written version of the lecture, you can find it as In the Zone, in Philosophy and Sport, edited by Anthony OHear and published by Cambridge University Press in 2013.)

But that wasnt the end of it. Now that I had found a way of combining philosophy and sport, I was keen to do more of it. It struck me that there were a number of other sporting topics that could benefit from similar philosophical scrutiny, and that I was as well placed as anybody to supply it. I had recently built myself a website, and so I started posting a series of essays on sporting themes. Within a few months the subjects included the rationality of fandom, road cycle racing and altruism, national identity and sporting eligibility, and the moral standing of different sports.

This volume is the eventual upshot of those early efforts. It contains eighteen chapters on interlinked aspects of the sporting world. I think of them as telling us as much about philosophy as about sport. If there is a common form to the chapters, each starts with some sporting point that is of philosophical significance. A first step is to show how philosophical thinking can cast light on the sporting topic. But in nearly all cases the spotlight of illumination is then reversed. The sporting example tells us something new about the philosophical issues, by highlighting ideas that are obscured in more familiar contexts.

The chapters fall into five sections: Focus, Rules, Teams, Tribes, and Values.

Part I, Focus, is about the mental side of sport. The chapters in this section take off from my original interest in decision-making and fast sporting skills, and go on to an analysis of choking and the yips, the twin perils that lie in wait for every unwary sports performer.