A Dell Trade Paperback

Published by

Dell Publishing

a division of

Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

Copyright 1976 by

The Gesell Institute of Child Development,

Frances L. Ilg, and Louise Bates Ames

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

For information address Delacorte Press,

New York, New York.

The trademark Dell is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

eISBN: 978-0-307-81341-1

Reprinted by arrangement with Delacorte Press

v3.1

To our daughters,

Joan and Tordis,

and our grandchildren,

Carol, Clifford, Karl and Whittier

CONTENTS

chapter one

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE AGE

The Four-year-old is a funny little fellow, and if you can accept him as such, you will appreciate and enjoy him for what he is. If, on the other hand, you take a sterner stance and feel that his boasting, his swearing, his general expansiveness, and his often out-of-bounds behavior is wrong, both you and he may have an unnecessarily hard time of it.

For the most part, we have found the boy or girl of this age to be joyous, exuberant, energetic, ridiculous, untrammeledready for anything. What a change he offers as compared to his more difficult, demanding, Three-and-a-half-year-old, just-earlier self! If at times he seems somewhat voluble, boastful, and bossy, it is because it is so exciting for him to enter the fresh fields of self-expression that open up at this wonderful age.

The child at Three-and-a-half characteristically expressed a strong resistance to many things the adult required, possibly because in his own mind the adult was still all-powerful. Four has taken a giant step forward. All of a sudden he discovers that the adult, though still quite powerful, is not all-powerful. He now finds much power in himself. He finds that he can do bad things, from his point of view, and the roof does not fall in.

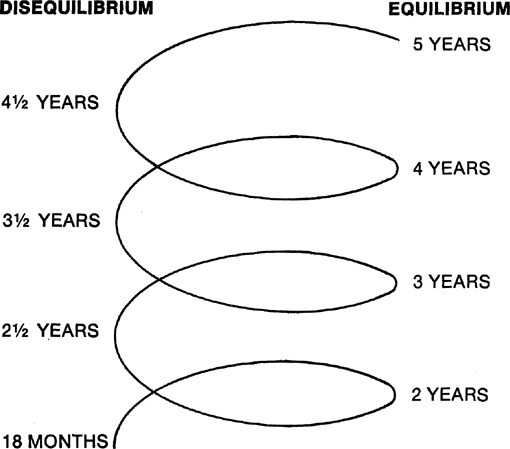

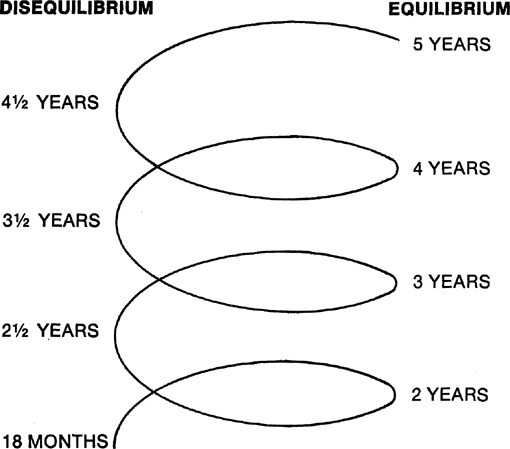

More than this, following its seemingly built-in plan shows, is an age when the child is characteristically in a nice state of equilibrium.

Emotional exuberance has its positive as well as its negative side. The typical Four-year-old loves adventure, loves excursions, loves excitement, loves anything new.

Figure I

Alternation of Ages of Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

He adores new people, new places, new games, new playthings, new books, new activities. No one is more responsive to the adult effort to entertain. He will accept what you have to offer with delightfully uncritical enthusiasm. So, it is a pleasure to provide the child of this age with new toys, books, clothes, experiences, informationbecause any of these things make his eyes sparkle so, because he is so wholeheartedly appreciative.

In fact, Four loves many things, but his emotions tend to be definitely extreme. He loves a lot and he hates a lot. In fact, his hates may be equally as strong as his loves. One can never be quite certain what it will be that will stimulate his hate, but whatever it is, his feeling should be fully respected, at least within reason.

With those children who have a tremendously strong attachment for their mothers (and that is most) there may be especially strong hatred expressed for anything that changes her in the childs eyes. He may hate certain jewelry she wears; he may hate it if she changes her way of wearing her hair. Or, he may especially hate a special look on her face that tells him that she is displeased with him.

He may hate squash, or any other food to which he takes a dislike. Or, he may (alas) hate certain people. He especially hates things that he considers ugly, and may at times express a quite remarkable aesthetic sensitivity.

Four loves things that are new. The Three-year-old has a conforming mind. Four has a lively mind, and new thoughts and ideas or bits of information may please him as much as do new toys. That is why it is so much fun to talk with him. His incessant whys may sometimes pall, but often they lead the way to enthusiastic information-giving on the part of the adult. It is fun to inform somebody who so enthusiastically wishes to be informed.

The key to the Four-year-olds psychology is his high drive combined with his fluid imagination. Four is, indeed, highly versatile. What can he not do? He can be quiet or noisy, calm or assertive, cozy or imperious, suggestible or independent, social, athletic, artistic, literal, fanciful, cooperative, indifferent, inquisitive, forthright, humorous, dogmatic. He is many people in one.

The typical Four-year-old is also speedy. Each thing he does, he does quickly, and he is also speedy as he moves from one interest to the next. For the most part, he does a thing once, and thats enough. He isnt interested in perfection; he is interested in getting on to the next activity. Behavior is fluid, and if he does stay with a single activity, that single activity may change so rapidly as to make your head spin.

A good example of the often quite remarkable fluidity of Fours imagination can be seen in his drawing. A Four-year-old in spontaneous drawing may quite typically start with a tree, which turns into a house, which turns into a battleship. Or, even more fluidly, his persons foot can grow so large that it develops large toes that turn out to be the back of a bird. And that turns out to be a roller coaster. And that turns out to be the back of the roller coaster. (At that point, your Four-year-old may very likely run out of paper.)

Fluidity can be expressed in media other than pencil and paper. For instance, two boys, playing in a sand-pile, decide that they are making volcanoes. However, when it is suggested to them that the volcanos erupting, as they had planned, might be too messy, they themselves spout a little and then give up the volcano plan and decide they are digging for dinosaur bones. No bones being forthcoming, they talk awhile about how old dinosaurs get to be (nine thousand years, they think) and then turn their sand into imaginary snow and make snowballs (which do not stick together very well even with the addition of water). So, they turn their snowballs into rotten eggs and say that the last one to talk is a rotten egg. (All this within five minutes of play.)

It is no wonder that adults have to keep on their toes to keep up with speedy, fluid, fanciful Fours. But, fluid as they are, there still remains some of Threes me-too quality. If you ask one child in a group what street he lives on, each child in the group then wants to tell where he or she lives, and all may be surprisingly patient and polite until everyone has had a turn at giving this interesting information.

It may be that Fours expansiveness is sometimes a little too much even for him. At any rate, he likes and respects boundaries and limits, which he does not always have within himself, and which, therefore, often have to be supplied. In fact, we find that many Fours like very much the verbal restraint of as far as the tree, as far as the gate. Others can be reasonably well contained if told, Its the rule that you do (or do not do) so-and-so.