Table of Contents

PRAISE FORAMERICAN WASTELAND:

While the very best way to end the food hardship now faced by 49 million Americans would be to increase wages and expand the federal safety net, doing more to recover excess food could play an important role in feeding more hungry Americans and filling in the gaps when those other efforts fall short. Jonathan Blooms fact-filled book is an important wake-up call and prod to action.

Joel Berg, Executive Director, New York City Coalition Against Hunger, author of All You Can Eat: How Hungry is America?, and former USDA Coordinator of Food Recovery and Gleaning

How is it that America can be dumping so much food, yet still be overweight? It seems that something is askew, and Blooms work uncovers it eloquently and with great insight. Bloom reminds us that good stewardship of our resources is not only easy, it is the key for us to thrive.

Jeff Barrie, Documentary Filmmaker, Kilowatt Ours

A fascinating read that explores the full depth of food waste from every angle. American Wasteland is chock full of research showing how essential it is that we strive to raise awareness that food is not trashit has no place in landfills. Bloom also addresses composting, touching upon its many economic, social, and environmental benefits.

Wayne E. King Sr., President, U.S. Composting Council

Food isnt just gas for the body; it binds us together as a people and its the key to our future. American Wasteland is a bold call to arms, providing shocking examples of waste (most of it preventable), as well as strategies to divert that food back into communities, insuring that NO food goes to waste, and no citizen goes hungry.

Robert L.E. Egger, President, D.C. Central Kitchen/ Campus Kitchens Project/V3 Campaign

As much about the food we eat as it is about the food we discard, American Wasteland draws our attention to a culture of excess and wastefulness and the threats that this cultural mindset poses economically, environmentally and ethically. Bloom challenges us to open our eyes and engage ourselves in an issue that we cannot ignore.

Josh Viertel, President, Slow Food USA

Bloom does a thorough job identifying places in the food chain where food is wastedfood that could feed the hungry instead. American Wasteland is an excellent read for anyone who wants to know how surplus and scarcity can exist in the same country or in the same city.

Jilly Stephens, Executive Director of City Harvest

TO EMILY, without whom this book would not exist and the sun would not rise.

TO BRUCE, without whom this book would have been finished sooner, but for whom I count my lucky stars.

INTRODUCTION

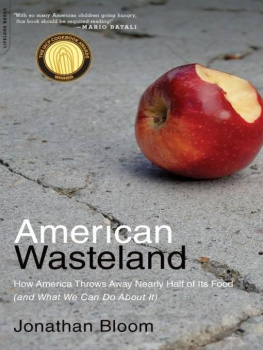

A forsaken orange sits in a Raleigh, North Carolina, parking lot.

PHOTO BY JONATHAN BLOOM

Every day, America wastes enough food to fill the Rose Bowl. Yes, that Rose Bowlthe 90,000-seat football stadium in Pasadena, California. Of course, thats if we had an inclination to truck the nations excess food to California for a memorable but messy publicity stunt.

As a nation, we grow and raise more than 590 billion pounds of food each year. Even using the more conservative figure would mean that 160 billion pounds of food are squandered annuallymore than enough, that is, to fill the Rose Bowl to the brim. With the high-end estimate, the Rose Bowl would almost be filled twice over.

If those numbers dont hit home, consider that the average American creates almost 5 pounds of trash per day.

How we reached the point where most people waste more than their body weightor at least the average American body-weighteach year in food is a complicated tale. In short, Americans gradual shift from a rural, farming life to an urban, nonagricultural one removed us from the sources of our food. Our once iron-clad guarantee of inheriting generations of food wisdom became less so, as busier lives forced many of us to leave the kitchen or spend less time there. Convenience began to trump homemade, and eating out drew level with dining in. We have higher standards for our meals, but diminished knowledge about how to maximize our use of food. Many of us dont even trust our noses to judge when an item has gone bad. Yet, our awareness of pathogens has multiplied, and we apply safety rules to food with the same zealous caution that we apply to allergies, kids walking to school, and most everything in modern life.

Certainly, some food loss is unavoidable. For example, there are many potential pitfalls, such as harsh weather, disease, and insects invading farmers fields, that are outside of our control. And then theres storage loss, spoilage, and mechanical malfunctions. I classify all of the above factors as loss, not waste (also omitted when I use the term waste are inedible discards like peels, scraps, pits, and bones). Broadly speaking, I consider food wasted when an edible item goes unconsumed as a result of human action or inaction. There is culpability in waste. Whether its from an individuals choice, a business mistake, or a government policy, most food waste stems from decisions made somewhere from farm to fork. A grower doesnt harvest a field in response to a crops lowered price. Grocers throw away imperfect produce to satisfy their (and, as consumers, our) obsession with freshness. We allow groceries to rot in our refrigerators while we eat out, and when at restaurants we order 1,500-calorie entres only to leave them half eaten.

Were not going to revert to an agrarian society anytime soon, but that doesnt mean we cant have a greater appreciation of our food. While completely eliminating food waste may be impossible, reducing it isnt. Improvements are needed at all steps of the food chain, but most importantly at the part that involves us. Buying wisely, and maximizing our food use once its in our possession, would go a long way toward minimizing that daily Rose Bowl-sized pile of waste.

My fascination with wasted food started in the sweltering lair of one of Americas oldest food-recovery groups, D.C. Central Kitchen, in 2005. Id been cruising through most of my twenties as an increasingly food-focused journalist, but I hadnt quite found my niche. That summer day in our nations capital, my task was to man an industrial-sized vat of pasta. This was not a plum assignment in a building without air conditioning. Yet the jobs mindlessness granted me time to look around while I stirred the spaghetti with an oar. I noticed a variety of foods that somebody hadnt wanted. And it was all good stuff, too. Were talking about racks of lamb, ribs, and nice vegetables. Such abundance, all waiting for redistribution to the hungry.

What was the story? Where did these foods come from? Why were they cast away? And what happens in cities that lack such food-recovery organizations?

My curiosity about these questions led me to investigate the extent of food waste in America. I declined a traditional journalism job after graduation in order to focus on food wasteeven if it made future meals with friends and family a touch uncomfortable. I launched a blog (WastedFood.com) in late 2006. Along the way, I began to be interviewed and was invited to give talks on the subject. Its an odd thing to call oneself a food-waste expert, but lifes funny like that.