Chris Kitchin Astronomers' Universe Exoplanets Finding, Exploring, and Understanding Alien Worlds 10.1007/978-1-4614-0644-0_1 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012

1. Because We Live on One! or Why Planets and Exoplanets Are Important

Abstract

Because we live on a planet, planets other than the Earth are fascinating, significant and important to us, whether they form part of the solar system, belong to stars other than the Sun, or even float freely in space independent of any star. As well as a purely intellectual interest in planets and exoplanets, there is also the hope that one day humans might set up colonies on some of them. Thus providing a safety net against the remote chance of human kind being wiped-out by a large meteorite impact with the Earth or the far more likely possibility that we shall render the Earth unfit for life ourselves.

Because we live on a planet, planets other than the Earth are fascinating, significant and important to us, whether they form part of the solar system, belong to stars other than the Sun, or even float freely in space independent of any star. As well as a purely intellectual interest in planets and exoplanets, there is also the hope that one day humans might set up colonies on some of them. Thus providing a safety net against the remote chance of human kind being wiped-out by a large meteorite impact with the Earth or the far more likely possibility that we shall render the Earth unfit for life ourselves.

While any exoplanet is better than none, if we are truly honest with ourselves then our interest is even more parochial than that what we really want to find are exo-Earths.

Exo-Earths are planets inhabitable by human-kind. A twin-Earth immediately ready for us to live on would be best of all but they will be very few and far between. Most people would probably settle for an exo-Earth that was 75% or 80% of the ideal.

Thus the holy-grail of exoplanet-hunting teams is currently to find the little-blue-dot (see ) that would mark the discovery of an exo-Earth and missions such as Kepler have this amongst their primary aims. Our requirements for an exo-Earth would include a reasonable gravitational pull (we wouldnt want to weigh half a ton or alternatively to risk floating off into space when attempting a high jump), a comfortable temperature and a breathable atmosphere. Because an exo-Earth must be just right for ourselves, like the temperature of Baby Bears porridge and the softness of his bed in the tale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears , they are also often referred to as Goldilocks Planets.

We have yet to find a true Goldilocks exoplanet. The nearest approach so far is an exoplanetary candidate (i.e. a star that has been observed to change brightness in a way that might arise from the transit of an exoplanet across its disk, but for which the reality of the exoplanet remains to be confirmed see ). The announcement of the detection of KOI 326.01 occurred during the final stages of writing this book (early 2011) and the star will undoubtedly be the centre of an intensive observing campaign from this time onwards so confirmation or otherwise of its exoplanet should occur fairly quickly.

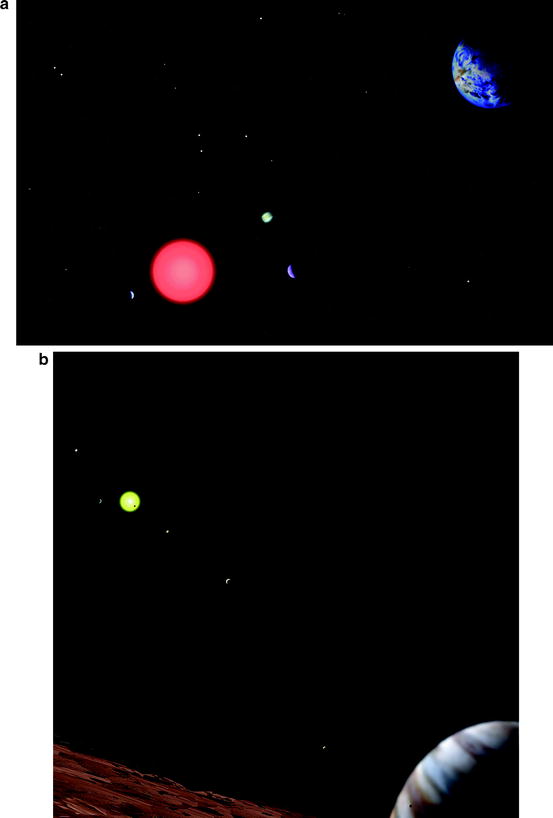

A remarkable planetary system surrounds Gliese 581 (Figure ), a faint cool star in Libra that lies just 20 light years away from us. Six exoplanets are thought to orbit the star, although the two most recent discoveries remain to be confirmed. Three of the planets verge on being habitable. The very recently discovered (and unconfirmed) exoplanet, Gliese 581 g could have an average surface temperature between 30C and 10C, which would make conditions comparable with the fringes of Antarctica. It seems possible though that the planet has a reasonably dense atmosphere so the average temperature could be higher than these values. Furthermore the planet always keeps the same face towards its star (like our Moon always keeps the same face towards the Earth) so the day side will have a much higher temperature than the average and the night side a much lower one. In the twilight zone between the day and night sides of the planet regions should exist that have ideal temperatures for humans. Gliese 581 g has about three times the mass of the Earth and if it is rocky like the Earth, its surface gravity will be about 40% higher than that of the Earth a 70 kg human would weigh 100 kg on the planet.

Figure 1.1

(a) An artists impression of the star Gliese 581 with the (unconfirmed) exoplanet Gliese 581 g in the foreground. Three other planets of this six-planet system are shown in the distance. (b) An artists impression of the star Kepler-11 seen from near an hypothetical satellite of the outermost planet, Kepler-11 g. The five inner planets are shown, with one in transit across the stars disk. A second (also hypothetical) satellite of Kepler-11 g is included which is casting a shadow onto its planet. (Copy right C.R. Kitchin 2010).

In addition to KOI 326.01, in early 2011 the Kepler team also announced another 53 exoplanetary candidates that were in or near the habitable zones of the stars. Four of these are super-Earths (i.e. with radii probably less than twice that of the Earth) while the remainder are comparable with Neptune or Jupiter in size or even larger. Super-Earths could potentially be inhabitable by humans, although other things being equal, their surface gravities would be up to twice that of the Earth. Planets of the size of Neptune or Jupiter are probably not inhabitable by humankind though other life forms might well be able to exist upon them. However any satellites of such planets will also be within the stars habitable zone and the larger such objects could have atmospheres (like Saturns Titan) thus potentially providing the conditions required for the existence of life.

No exoplanets at all are known with oxygen-rich atmospheres. Thus a true twin-Earth remains to be found at the time of writing, but there can be little doubt that success in that search is only a matter of persistence. Of course, when we do find an exo-Earth or a twin-Earth we may also find it to be inhabited by ETs (intelligent Extra-Terrestrials or alien creatures) further speculation on that topic however is left for later on in this book.

In addition to having a parochial interest in discovering a twin-Earth, many people would probably also like to know whether or not our whole solar system has any look-alikes. The multi-planet system Gliese 581 has already been mentioned, but a simple inspection of the 600 or so known exoplanets would suggest that the answer to that query must be No. From the first exoplanet found around a normal star in 1995 onwards, the majority of exoplanets have been found to huddle very near to their host stars often very much closer to their stars than even Mercury is to the Sun. Many of these close-in exoplanets are also gas giants as large as or larger than Jupiter. Furthermore, three quarters of currently detected exoplanets are singletons i.e. the only exoplanet known for their host star.

There are though over 50 known multi-exoplanet systems with up to six confirmed planets in a single system, so clearly the solar system is not unique in possessing many planets. However these exoplanetary systems also huddle close to their stars the very recently discovered Kepler-11 for example has six exoplanets that are all closer to their star than Venus is to the Sun (Figure ). Only 10% of the multi-exoplanet systems have planets as far out or further out from their host stars as Jupiter is from the Sun.