Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

p53: The Gene that Cracked the Cancer Code by Sue Armstrong

Atoms Under the Floorboards by Chris Woodford

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

Chilled by Tom Jackson

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Breaking the Chains of Gravity by Amy Shira Teitel

Suspicious Minds by Rob Brotherton

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Electronic Dreams by Tom Lean

Sorting the Beef from the Bull by Richard Evershed and Nicola Temple

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Furry Logic by Matin Durrani and Liz Kalaugher

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

My European Family by Karin Bojs

4th Rock from the Sun by Nicky Jenner

Patient H69 by Vanessa Potter

Catching Breath by Kathryn Lougheed

PIG/PORK by Pa Spry-Marqus

To my parents, with whom I was furious from the age of eight for not noticing my initials would be E.T.

... I admit it paid off.

Contents

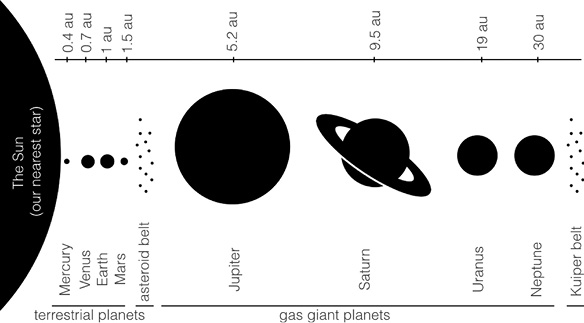

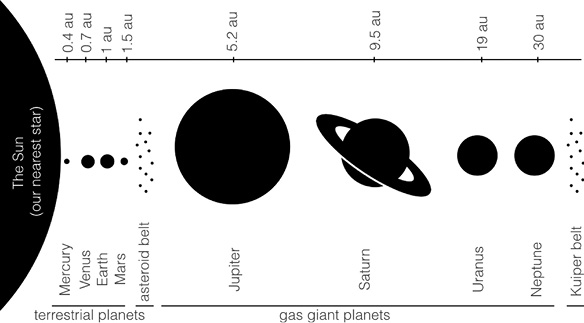

Figure 1 Our Solar System. Astronomical units (au) are used to compare the immense distances between the planets. 1au is the distance from the Earth to the Sun. (Due to the huge size difference between the terrestrial and gas giants, this image is not to scale.)

In the early 1990s, we knew of eight planets:

Mercury,

Venus,

Earth,

Mars,

Jupiter,

Saturn,

Uranus,

Neptune.

And the dwarf planets, Ceres (within the asteroid belt) and Pluto (within the Kuiper belt).

The first four are the terrestrial planets, with rocky surfaces and thin atmospheres. The next four are the gas giants, 15300 times more massive and engulfed in atmospheres thousands of kilometres thick.

But these were not the only worlds out there.

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The Blind Men and the Elephant by John Godfrey Saxe,

based on the Indian fable

There is an Indian fable about six blind men examining an elephant. Each reaches out to touch a different part of the unknown animal. One man finds the smooth membrane of the elephants ear. Another holds the curved tusk, while a third grasps at the thin tail. The fourth man touches the elephants trunk and the fifth wraps his hands around one leg. The final man presses his palms against the elephants broad flank. An argument then erupts over what an elephant truly looks like, since each man has only found part of the truth.

What would make you throw my book out of the window?

Winter sunlight was streaming through one such possible glass pane on the third floor of the University of Washingtons Department of Physics. Outside, the damp Seattle skyline was creating an impressive panorama, but all I could think about was a crushed copy of my book lying in a puddle.

In the chair opposite me was Tom Quinn, a thickly bearded astrophysicist who had spent decades working on models for planet formation. I had talked his ear off for the last 10 minutes listing all the world-changing feats I wanted my magnum opus to accomplish. Now we came to the crunch point: what would make a renowned expert in planetary science dismiss a book on alien worlds as rubbish? I expected Quinn to respond by ticking off essential topics on his fingers. Number one on his list would surely be the importance of hot Jupiters; the first discovered planets around stars like our own that smashed all previous formation theories into dust. Next in line might be the mysterious super Earths, whose sizes do not match anything circling our Sun. Are these miniature gas planets with suffocating atmospheres, or rocky worlds in size XXL?

Perhaps Quinn would mention the planets that orbit two twinned stars like the fictional home world of Luke Skywalker, or the other extreme where the planet has no sun at all. Then there were the worlds whose paths around their stars was so elongated that their seasons swing between fireball and snowball, worlds where the sun never sets, worlds entirely under water, or with a ground of molten lava. Alternatively, Quinn could say that the next big discoveries would be planets like our own Earth, with rugged coastlines that harboured strange forms of life.

Quinn did not make a list. Instead, he spoke frankly.

Our knowledge of planet formation is not complete, he said. We have seen only a tiny fraction of what is out there. If you presented what we know as a complete picture of what exists, then I would throw your book out of the window.

Quinns point was that the secrets of planets shared the conundrum of the blind men and the elephant. The myriad of worlds in our cosmos is an unseen creature that we are struggling to understand through the small sections we have so far uncovered.

The star speed gun

In 1968, Michel Mayor fell down an icy crevice and almost missed discovering the first planet orbiting another sun.

Mayor was an explorer. Born in 1942 in Lausanne on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, he grew up in a family with a love of outdoor activities. This expanded into a rather risky passion for high-altitude skiing and climbing, which led to him hanging precariously off an ice-laden ledge 26 years later. Perhaps it was this love of high places that led to Mayors obsession with the motions of the stars.

For his doctoral thesis at the University of Geneva, Mayor was searching for small deviations in a stars course due to the pull of gravity from our Galaxys spiral arms. It was a study that required recording the velocity of stars to impressive levels of precision. As Mayor worked on techniques to improve these measurements, the changes in the star motions that could be detected became steadily smaller. Eventually, even tiny wobbles of the star could be seen; wobbles caused by an object vastly smaller than the star itself a nudge from an unseen planet.

The problem with detecting planets is that stars are big and bright. Even the most massive planet in our Solar System, Jupiter, reflects just one billionth of the Suns light. This makes planets immensely hard to spot when they orbit another star whose own light is only a pinprick in the sky. Yet the technique Mayor was working with did not require astronomers to see the planet directly. Instead, they would measure the star wobbling as the planet orbited around it.

When talking about orbits, we normally think about a smaller object circling a stationary more massive body, for example the Earth circling the Sun, or the Moon circling the Earth. In actual fact, both bodies pull on one another and therefore both move. The pair orbit around their centre of mass ; a balance point in space between their two gravitational pulls.