The Georgian Star

Echo of the Big Bang

Other Worlds

The Light at the Edge of the Universe

Copyright 2012 by Michael D. Lemonick

Electronic edition published in October 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

For information address Walker & Company, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

A Division of Bloomsbury Publishing

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Lemonick, Michael D., 1953

Mirror Earth : the search for our planets twin /

Michael D. Lemonick.1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Extrasolar planets. 2. Earth. 3. Planetology. I. Title.

QB820.L46 2012

523.24dc23

2012009787

Visit Walker & Companys website at www.walkerbooks.com

First U.S. edition 2012

ISBN: 978-0-8027-7902-1 (e-book)

For Seymour Lemonick,

whose love and support

have been there since

before I can remember

Contents

The earth goes around the Sun. Thats whats going on!

These were the last words my father ever said to me. He said themalmost shouted themwith a vehemence and conviction that startled me. The fact that he could say anything at all was itself a surprise. Hed been semicomatose for nearly a week, unable to initiate movement or speech on his own. He would sometimes respond to questions, but only in a hoarse whisper, so faint that it was impossible to understand what he was saying. That afternoon, Id arrived at his room at the nursing wing of the retirement community he lived in, and said, Dad, whats going on? with the artificial heartiness you sometimes put on to convince yourself and others that everything is perfectly normal, even though its anything but normal. He barked out that single phrase, and then didnt speak after that. Two days later, he died.

At the time, those final words didnt make a bit of sense to me, but when I began to write this book, I thought about them again, and remembered the stories my father used to tell me when I was very young. He was a professor of physics at Princeton University and an extraordinarily popular teacher. When they hear my last name, gray-haired men still tell me how much they loved taking his classes a half century ago or more. He would present long-established ideas in physicsNewtons laws of gravity or Maxwells equations of electromagnetism or Einsteins theories of relativityas though he had just stumbled on these mind-blowing truths for the first time. He could barely contain his excitement, and his students couldnt help sharing it. The fact that the Earth goes around the Sun was a big deal when Copernicus first proclaimed it in the 1500s. And it still is!

I never took one of those classes. I got a different sort of physics education, delivered in the form of stories my father would tell late at night, as we drove home from visiting his family or my mothers in Philadelphia. He told stories about atoms and molecules and planets and stars, pitched at a level an eight-year-old could understand, but filled with the same excitement and wonder he shared with his students at Princeton. I remember the time he told the story of Halleys Cometabout how it returned every seventy-six years to light up the night sky, how it was passing by the year Mark Twain was born and again as he lay on his deathbed. It would be coming again, my father promised, in 1986, when I would be an unimaginable thirty-three years old. I couldnt wait.

Those late-night stories about the universe didnt inspire me to become a physicisttoo much math! They did, however, inspire me to become a journalist who never wanted to write about anything but science. I was intrigued, not only by what astronomers had learned already, but also by mysteries still unanswered. When my father first told me about the cosmos, astronomers didnt know about quasars, or black holes, or pulsars. They didnt know that most of the matter in the universe is not the atoms that make up stars, planets, and people, but rather a mysterious, invisible substance known as dark matter. They knew that the universe was expanding, but had no idea that the expansion is accelerating, driven by an equally mysterious force known as dark energy.

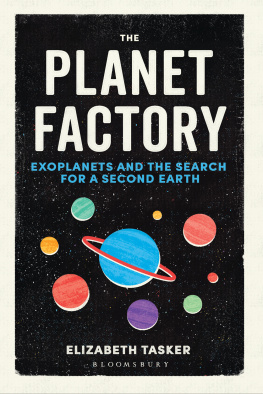

And they didnt know the answer to perhaps the oldest questions of all: Do planets orbit distant stars? Do any of them harbor life? Is the human species alone in the universe?

It wasnt that astronomers and physicists hadnt tried to answer these questions, but planets around other stars are excruciatingly hard to see. They lie tens of trillions, or even hundreds of trillions, of miles away. Stars appear tiny when you look up into the night sky, but planets are far tinier, and far dimmer. Finding planets around even the nearest stars turned out to be so difficult that hunting for distant worlds had become a fringe area of astronomy. Anyone who thought he or she could figure out how to do such a thing shouldnt be taken very seriously.

All of that changed in 1995, however, when Swiss astronomers found the very first planet orbiting a Sun-like star. In 1996, American astronomers found several more. The Americans, especially, had staked their careers on finding planets (the Swiss were working on other things as well), and they hadnt gotten a lot of respect. But once this small handful of pioneers had shown it was possible to find planets, their colleagues quickly changed their attitudes, and started looking too. Over the next decade and a half, the number of known worlds beyond our own solar system would climb into the tens, then the hundreds, then to more than a thousand.

But the ultimate goal of finding a Mirror Eartha planet of about the same size as our home planet, with the right mix of land and ocean and temperature so that life might have established a foothold and gone on to thriveremained just out of reach.

It wont be out of reach for long, though. By early 2012, it was clear that a Mirror Earth was finally within astronomers grasp. It likely would be only months, rather than years, before astronomers would be able to take my fathers dying words one step further by declaring: A Mirror Earth goes around a Sunlike starand heres where it is!

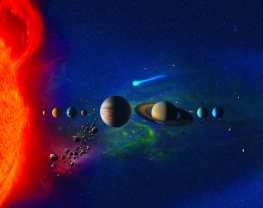

Five billion years ago, the Milky Way didnt look much different than it does today. It was, and remains, an enormous pinwheel some five hundred quadrillion miles across, made up of hundreds of billions of stars, rotating once every two hundred million years or so. Between the stars lay immense, swirling clouds of gas and dust, and every so often, one of these clouds would begin to collapse under its own gravity. The collapse might be triggered by a shock wave from a supernovaa star ending its life in a titanic explosionor it might be caused by the blast of radiation from a hot, blue supergiant star, or simply by the gravity of a star lumbering by.

Once it started, the cloud kept falling in on itself, getting smaller and denser, spinning faster and faster and, because of the spin, flattening itself out like a pancake. When it was about five billion miles across, one one thousandth of its original size, and one hundred million miles or so thick, the cloud was dense enough and spinning so fast that gravity could no longer force it to shrink any further. Particles of iron, nickel, and silicatesmolecules made of oxygen and siliconcollided and stuck together and began to grow larger.

But by now, the intense pressure in the densest part of the cloudthe very corewas heating it up to temperatures of millions of degrees. The searing heat ripped electrons away from atoms and forced atomic nuclei to overcome their natural repulsion, releasing enormous energy. The core of the pancake burst into life as a newly formed stara gigantic, self-perpetuating thermonuclear furnace that would burn for the next ten billion years. The star would one day be known as the Sun. Once the Sun flared into life, it had a quick and profound effect on the pancake that still swirled around it. The heat and light and intense magnetic fields emanating from the young star would collectively have swept most of the remaining gases out toward the edges of the pancake, leaving the rocky and metallic solids behind.