Copyright The Random House Group Ltd/ ESA, 2016

Cover design by Allison Warner; photographs ESA/NASA

Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: June 2017

Originally published in Great Britain by Century, November 2016

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Some of the images and captions included in this book were first posted by Tim Peake on his social media accounts during his mission on board the International Space Station.

ISBN 978-0-316-51276-3

E3-20170524-JV-PC

To Thomas and Oliver, who help me to see the world through new eyes every day

Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the Earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.

Leonardo da Vinci

Nature is painting for us, day after day, pictures of infinite beauty.

John Ruskin

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth, And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings; Sunward Ive climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds.

John Gillespie Magee, Jr.

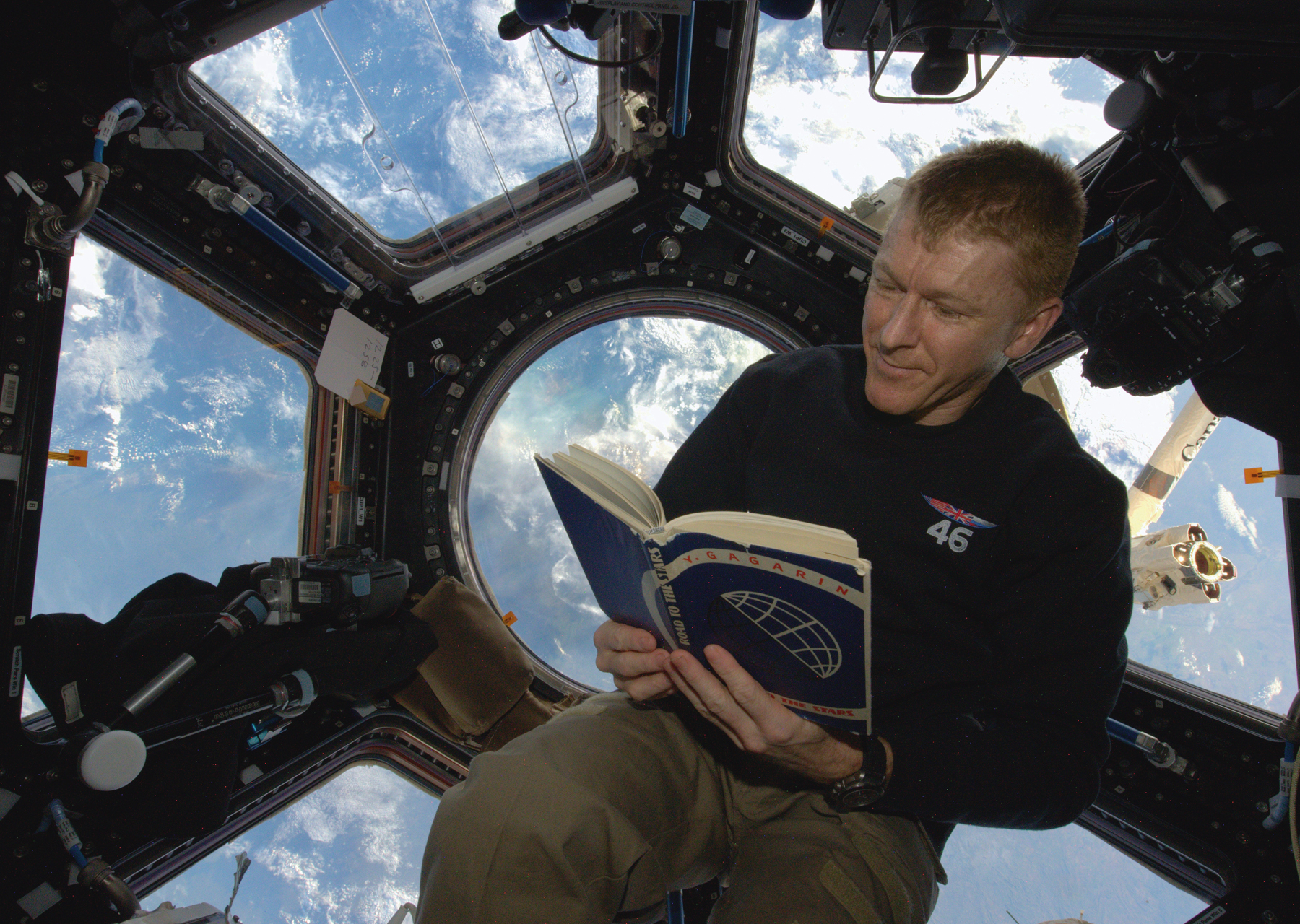

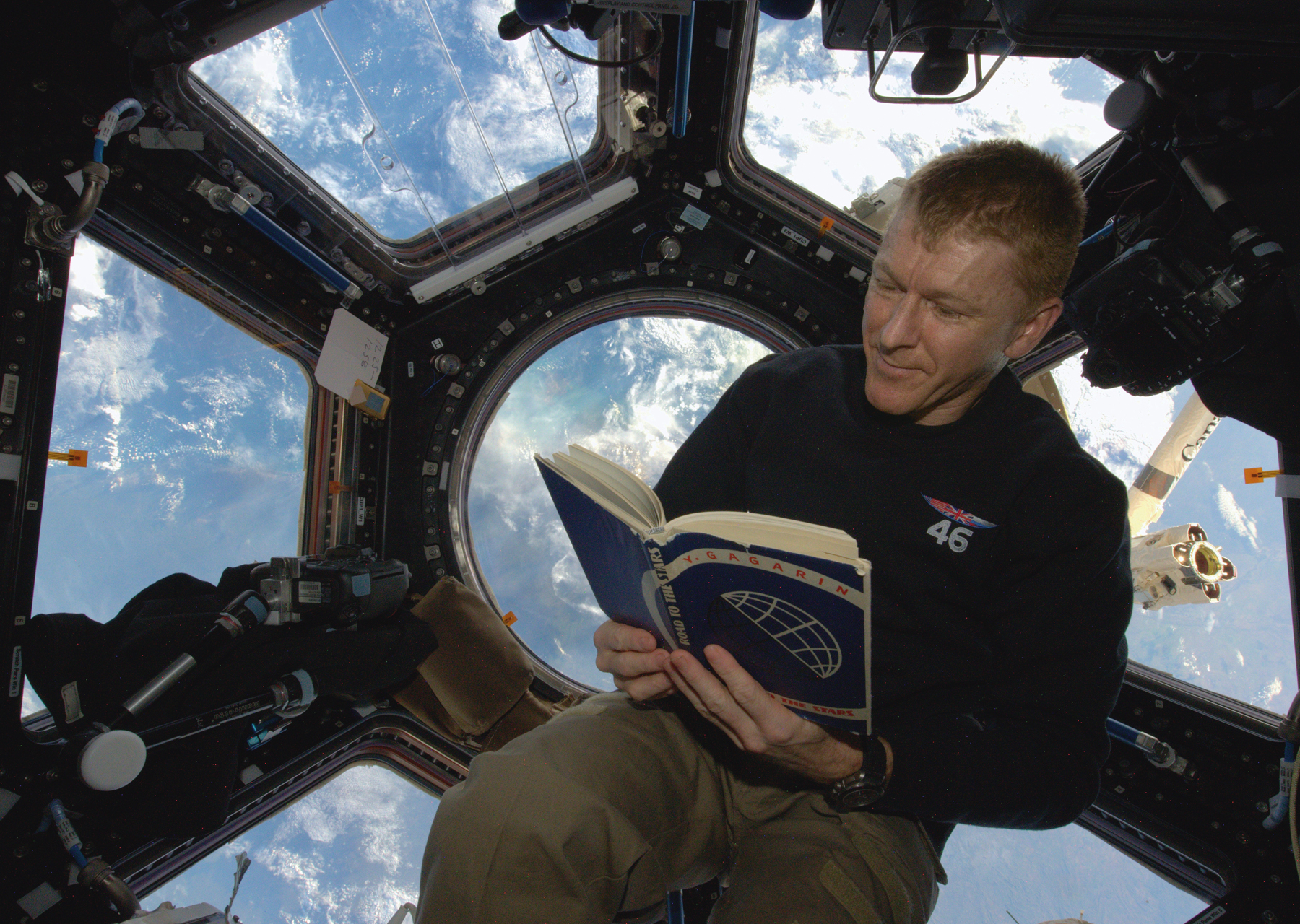

The view from the Cupola window on board the International Space Station.

One of the remarkable things about seeing the Earth from space is that by day, with the naked eye, its very hard to spot any signs of human habitation.

Instead, our planet reveals itself as a vast geological puzzle, its features spanning entire continents, sculpted by natures forces and the passage of time. Wind and rare precipitation have shaped the Sahara into a canvas of exquisite art, with sand dunes towering over 150 meters high clearly visible from space. Volcanoes trace the outline of Earths tectonic plates, often smoking gently and giving away the presence of an active core not far beneath. Glaciers carve out entire mountain ranges as they grind inexorably towards the oceans. By night its a different story. You can easily trace the pattern of human migration and settlement by the lights of towns, cities, motorways and man-made structures. Even our thirst for the planets resources stands outthe lights of a thousand fishing boats in the Gulf of Thailand or the dazzling oil fields in the Middle East.

Its impossible to look down on Earth from space and not be mesmerized by the fragile beauty of our planet. I was struck by just how thin our atmosphere really isthat tiny strip of gas that sustains all life and differentiates our planet from the barren, hostile conditions of Mars or Venus. I became determined to share this unique perspective of the one place we can all call home. It may come as a surprise to learn that I was not a keen photographer when I launched into space. Its not that I didnt enjoy photography; its just that I never seemed to have a good eye for a picture. In that respect I have a lot to thank planet Earth for: shes a beautiful subject and made my job extremely easy! Even my early attempts rewarded me with some stunning vistasthe Cascade mountains, frozen sea in the Hudson Bay and spectacular sunrises to name a few.

From the International Space Station (ISS) you can see over 1000 kilometers in any direction. Passing over the French Alps I could enjoy a view stretching from Greece to the UK with just the turn of my head. At first, the magnitude of this scene was a bit overwhelming, and my photographic skills did not extend much beyond point and shoot. However, as I settled into this new environment my perspective began to change. With sixteen orbits every day, it was not long before I felt I knew planet Earth pretty well! For example, it may sound strange, but I was talking about Madagascar recentlysomewhere I have yet to visitwith the familiarity of someone who has traveled there extensively. I began to focus on the details: noting the mountain lakes in the Himalayas that would lead me to Mount Everest, perhaps, or checking up on some small volcano in Kamchatka to see if it was still erupting. When traveling at nearly 30,000 kilometers per hour, this level of detail requires some careful planning.

Each morning, I would check to see where the ISS would be passing over, decide which pictures I would try to capture that day and then set several alarms to remind me. Often, my alarm would go off and Id have my hands full of a science experiment or be in the middle of a maintenance activitya case of better luck next time. However, there was a huge sense of satisfaction when all the planning paid off and I was rewarded with a perfectly lit overhead pass of the Pyramids, say, or a rare glimpse of Antarctica. As much as I enjoyed the hunt for those more elusive targets, many of my most treasured pictures were not the result of meticulous planning. Often I would just happen to be passing by the Cupola window and be struck by the most incredible viewa sea of thick green fog as we traveled through the aurora borealis or the disco lights of a hundred lightning flashes along a massive storm front.

Night photography in low-light conditions presented a new set of difficulties. Reflections from the numerous light sources inside the ISS were a constant problem. We used a blackout curtain around the window with a hole for the lens to poke through to prevent this from ruining a picture. The next challenge was how to get a shot in sharp focus with long exposure times and so much relative motion between the camera and the object. The best method relied mainly upon a steady hand and a good eye for tracking targetssomething for which my previous job as a helicopter pilot had prepared me quite well. As someone who had only ever used auto mode on a camera before, I never imagined that I would be intuitively adjusting aperture, shutter speeds and ISO settings depending on the rapidly changing lighting conditions, nor discussing the merits of a particular lens over dinner in space with my fellow astronauts. Camaraderie on a space station is clearly important and photography is one of the many common interests that astronauts from all nations can share. In the first few weeks on board the ISS, my pictures certainly owed a great deal to the patient advice of crewmates Scott Kelly and Tim Kopra.