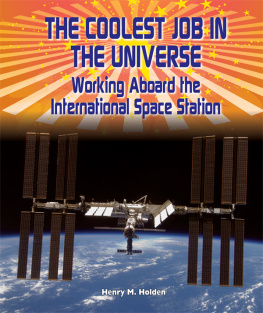

Would You Want a Job in Outer Space?

Traveling more than seventeen thousand miles per hour in constant orbit around Earth, astronauts live and work aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Despite the hostile environment of space, the ISS has suitable living conditions for its workers. Astronauts breathe clean air, eat shrimp cocktail, exercise daily, and take out the trashin zero gravity, of course. Floating around the ISS, the astronauts have important jobs, conducting experiments and completing research projects. Author Henry M. Holden explores the base camp to the universe from its design and construction to the amazing astronauts who work there.

About the Author

Henry M. Holden, with a background in the telecommunications industry, writes for children and adults. He has published several books for Enslow Publishers, Inc.

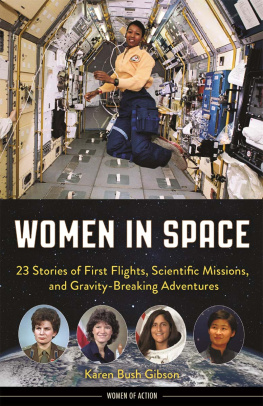

Image Credit: AP Images / NASA

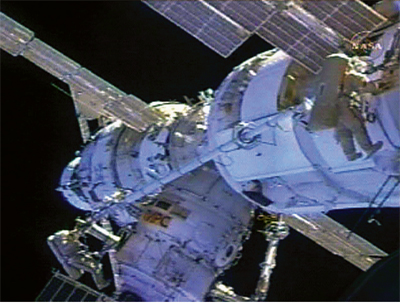

This view of the International Space Station was taken after the space shuttle Atlantis undocked from the orbital outpost on September 17, 2006. As the ISS orbits Earth, it comes in constant contact with space junk.

It was Sunday, October 24, 1999. The U.S. Space Command, near Colorado Springs, Colorado, was watching two objects on its radar. The objects, the International Space Station (ISS) and the remains of a Pegasus rocket, were screaming toward each other at a combined speed of almost 35,000 miles (56,327 kilometers) per hour. If they collided, the space station would be destroyed. The piece of rocket had been drifting in space for many years, unable to return to Earth. The ISS had only been in orbit for about a year. Space Command predicted that the two would pass less than a mile apart. That was a serious threat to the ISS. Ground controllers remotely fired small engines on the ISS and changed its orbit slightly to prevent a possible collision with the old rocket.

As of 2011, the Joint Space Operations Center is monitoring 22,000 man-made orbiting objects.

There are other objects, too small to be tracked from Earth, speeding through space. Small flecks of paint can damage a cockpit window on a space shuttle. For example, a tiny speck of paint from a satellite dug a pit in a space shuttle window almost a quarter-inch (.64 centimeters) wide.

More than 22,000 objects larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters) are currently tracked by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network. Only about 1,000 of these represent operational spacecraft; the rest are orbital debris. The estimated population of particles between .4 inches and 4 inches (1 to 10 centimeters) in diameter is approximately 500,000. Fortunately, much of this debris will eventually burn up, falling back to Earth.

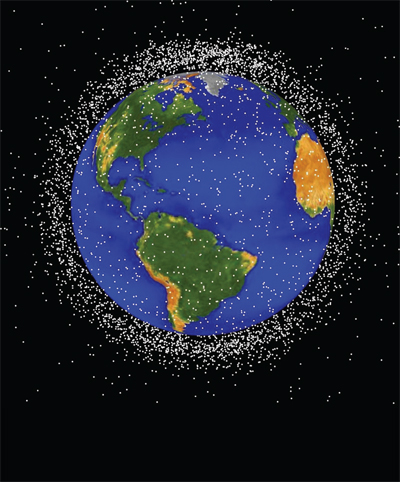

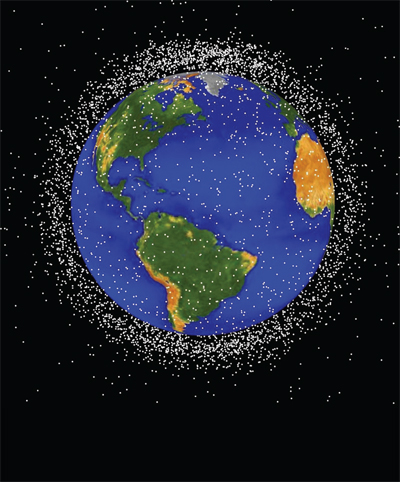

Image Credit: NASA Orbital Debris Program Office

This computer-generated image shows objects in Earth orbit that NASA is currently tracking. About 95 percent of the objects shown in the image as white dots are space junk.

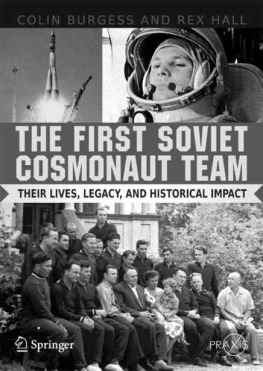

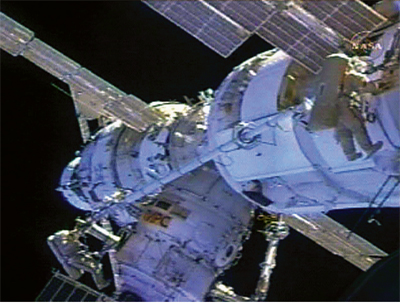

Image Credit: AP Images / NASA TV

In this image from NASA TV, space station commander Pavel Vinogradov (right) and astronaut Jeff Williams (left) prepare to replace a camera on the outside of the ISS during a spacewalk on June 1, 2006. The ISS can be a dangerous place to work, especially when astronauts perform spacewalks.

The ISS can be a dangerous place to work. Dust-sized meteorites can be a risk to spacewalking astronauts. The particles whiz by at 17,500 miles (28,163 kilometers) per hour. These tiny objects are traveling faster than a bullet. To protect themselves, astronauts wear space suits that act like bulletproof clothing. The suits are made of layers of Kevlar, Teflon, and aluminum Mylar. Any hole or tear in the space suit could cause a rapid and fatal decompression. However, the risk to the astronauts is low because they are such small objects in space. Still, to lower the risk, they do not stay outside the ISS for extended periods.

Despite a close call on June 28, 2011, the ISS has not yet been damaged by space junk. Even so, NASA takes the risk seriously. Its astronauts reinforce the stations most vulnerable parts during construction.

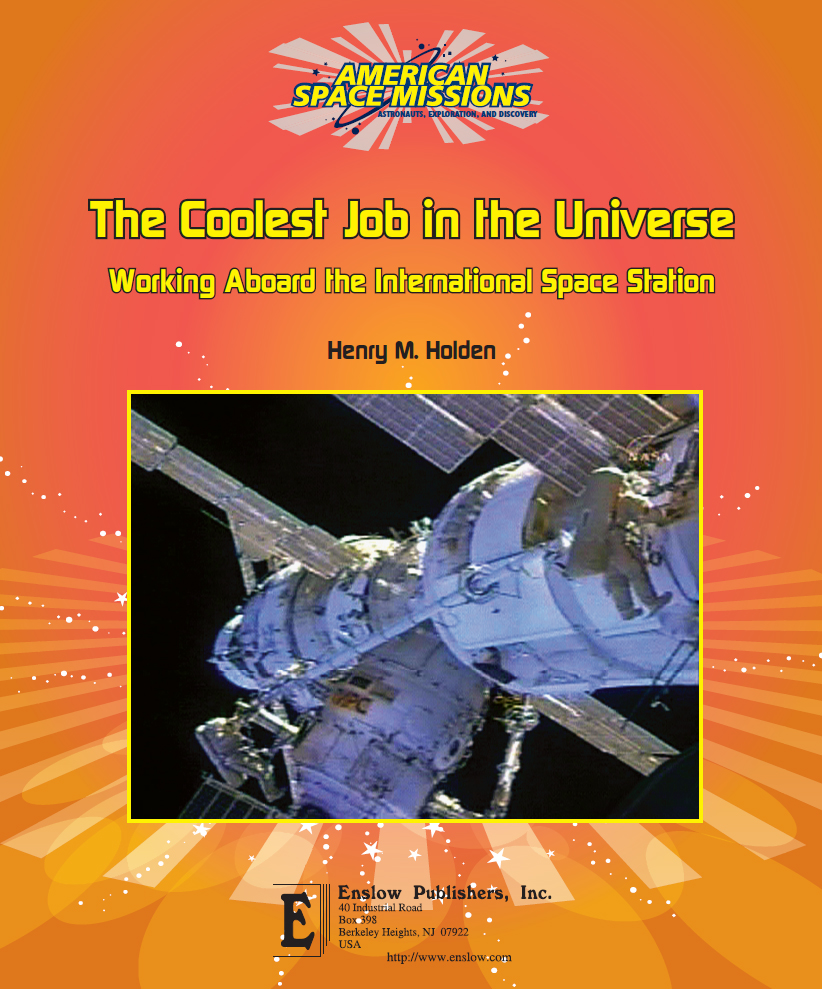

Image Credit: NASA Kennedy Space Center

The space shuttle Endeavour is suspended in a vertical position inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center on October 15, 1998. Endeavour was the first space shuttle flight for the assembly of the International Space Station.

Human space flight began in 1961. At first, the flights were short, but as humans learned more about space, the flights grew longer and longer. In November 2003, the International Space Station marked a milestone in space history. Humans had lived continuously in orbit for three years.

The International Space Station is the most ambitious engineering project in human history and the largest spacecraft ever put in orbit. The United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Russia, France, Germany, Italy, Canada, Japan, Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Brazil, Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain are all helping by either supplying parts or astronauts. When finished, the stations internal volume will be about the size of one 747-jet passenger compartment. The ISS is designed to provide pressurized living and working space for a crew of up to seven.

Parts for the ISS are carried in the cargo bay of the space shuttles. It will take about 160 spacewalks to assemble the ISS. When finished, it will be 361 feet (110 meters) wide, 290 feet (88 meters) long, about 14 stories high, and it will weigh about 500 tons (about 1 million pounds).

The ISS has three main sections. They are research modules, service modules, and living or habitation modules. Russia launched the first section of the ISS, the Zarya module, in November 1998. It provided the initial power and propulsion. The United States space shuttle Endeavour carried the U.S.-built 12-ton (26,880 pounds, 12,193 kilograms) Unity connecting module about two weeks later. These two modules had never been connected and had to fit perfectly the first time. Endeavours crew successfully attached the modules during the twelve-day mission. A third section, Zvezda, joined up with the station in July 2000. Zvezda provided living quarters and life-support systems. Destiny, the United States science laboratory, was attached in February 2001.

On October 31, 2000, astronaut William Shepherd and cosmonauts Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev flew to the station on a Russian Soyuz rocket. They became the ISSs first full-time crew. Krikalev served as the flight engineer, responsible for the systems. Shepherd served as the expedition commander, and Gidzenko served as the Soyuz commander. The crew lived on the ISS for four months. However, before they arrived, three space shuttle crews visited the ISS, stocking it with supplies and equipment.