Elizabeth Howell, foreword by David Williams, M.D.

by Dave Williams, M.D.

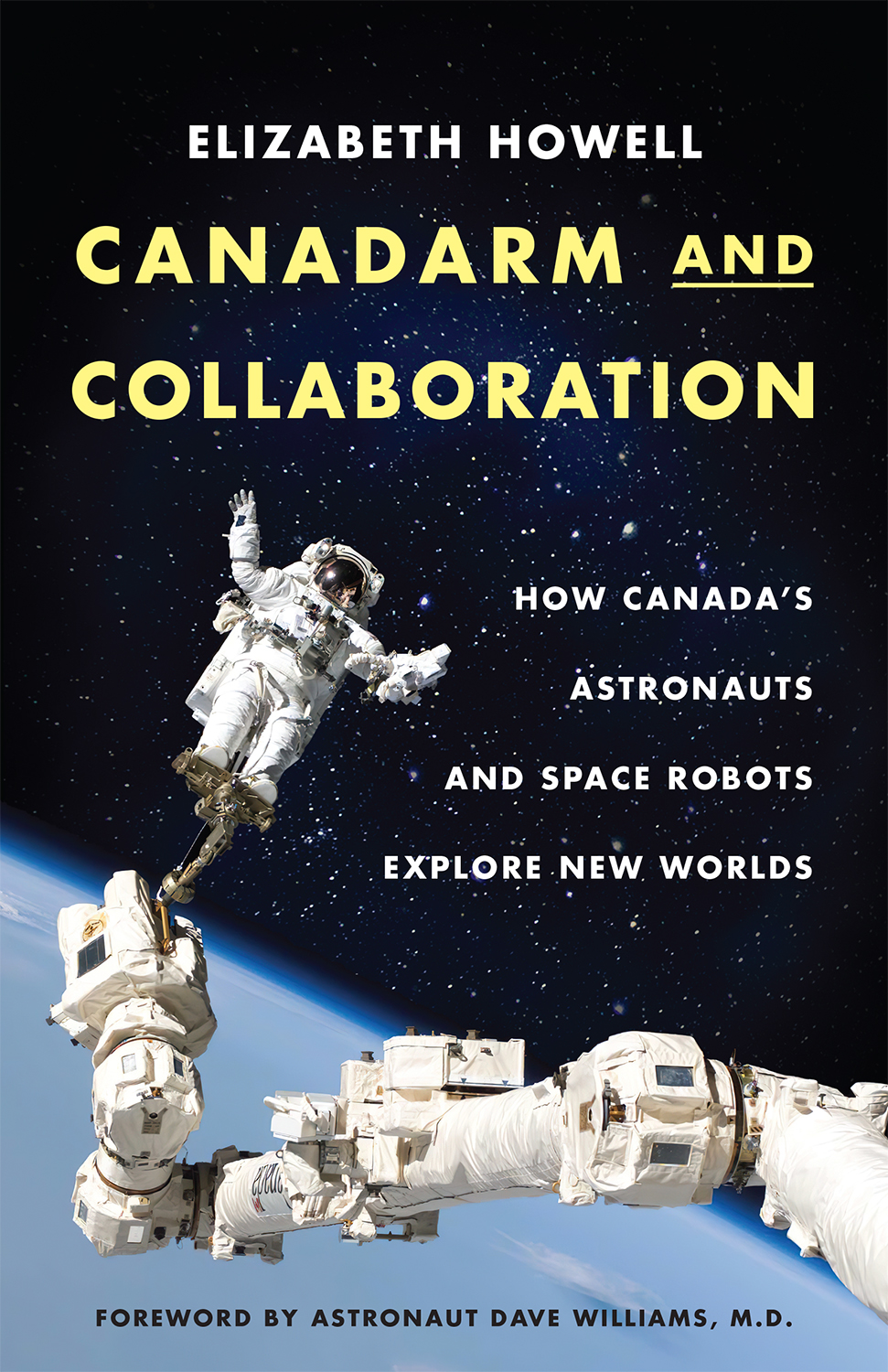

In the distance was the beautiful blue oasis of the planet Earth cast against the black infinite void of space. It was a moment of a lifetime, riding on the end of an icon of Canadian technology, the Canadarm2, with the Canadian flag on my shoulder. I felt immense pride in being able to follow in the footsteps of past Canadian space pioneers on a path to space that would be pursued by the next generation of Canadians in space. There is no question that Canada is a major spacefaring nation. After the spacewalk, one of the crew floated over to share a thought: Dave, we in the international program truly understand the space station is just the base for the Canadarm. The wry humour brought a smile to my face.

Exploration is a central part of Canadian history, and certainly a passion to push boundaries in aerospace is part of our legacy. As director of the NASA Johnson Space Centers Space and Life Sciences Directorate, I had a shelf in my office called the making the impossible possible shelf. On it there were two items. A model of the Avro Arrow was featured prominently. It sat in the centre of the shelf beside a photograph from one of my team members, David McKay, that showed an image obtained by a scanning electron micrograph from a Martian meteorite found in the Antarctic. The black-and-white image revealed chain-like structures that resembled bacterial organisms, suggesting that life may have once existed on another planet in our solar system. The image and associated scientific data caused considerable controversy in the scientific community; for me, what that image represented warranted inclusion on the shelf. The Arrow model had to be there. It would have stood alone on the shelf were it not for the amazing photograph. Many speculate on what would have happened if the Arrow had transitioned to full operational status. The photo made everyone who saw it speculate on another topic: one of the most fundamental remaining scientific questions, whether life exists or has existed elsewhere in our solar system.

The Arrow is remarkable for many reasons, notwithstanding the fact that the cancellation of the project resulted in a group of very talented Canadian aerospace engineers leaving Canada to help kick-start NASAs first human spaceflights. They all played critical roles that enabled the agency to achieve the goal of sending humans to the moon and back by the end of the decade. The third country to send a satellite to space, Canada has been part of space exploration from the beginning.

Many have dreamed of the possibility of human space exploration. The visionary Russian space pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky once said, The Earth is the cradle of humanity, but mankind cannot stay in the cradle forever. He and Robert Goddard are widely attributed with describing the principles of modern rocketry that underlie human space travel. It is not so widely known that William Leitch, the fifth principal of Queens University, described the principles of rocketry and human spaceflight in an 1861 article entitled A Journey Through Space. Four years before Jules Verne wrote From the Earth to the Moon, six years before Confederation and nearly 40 years before Tsiolkovskys and Goddards work, a Canadian scientist had described modern space travel. We might, with such a machine, transcend the boundaries of our globe, and visit other orbs. Had this discovery been made before 1998, I would have had Leitchs photograph on my shelf as well, but it wasnt until 2015 that Canadian space historian Robert Godwin would discover the original publication. It is clear, though, that Canada is well deserving of the title major spacefaring nation.

Occasionally Canadians can be understated in acknowledging the global impact of Canadian contributions to space exploration. Yet ours is a story to celebrate. It is a story of visionary scientific and engineering teamwork, a story of pushing the edge of the envelope by incredibly talented scientists, aerospace engineers, researchers, physicians and astronauts. It is a story that I am proud to have dreamed about, studied and lived as a physician, Canadian astronaut, scientist and senior executive at NASA. It is a story that continues to unfold as we set sights beyond the International Space Station in low Earth orbit to the Moon and ultimately to Mars. It is the story of humans pursuing their destiny as a spacefaring species, reaching out to other destinations in our solar system.

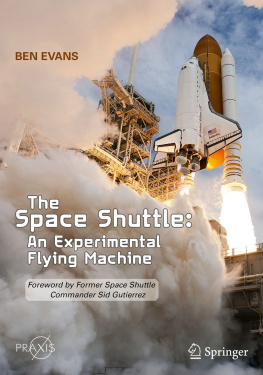

Elizabeth Howell is one of the few Canadian scientific journalists to write extensively about space exploration. She brings a unique perspective and true passion to sharing our history exploring space. Its all there. From the Arrow program through Mercury, Gemini and Apollo, the legacy of the Canadian space pioneers captures the readers attention. The early days of the Canadarm leading to the hiring of the first group of astronauts solidified our international reputation for excellence in space robotics and human space exploration. Describing the continued evolution through the shuttle program years to the era of the International Space Station with multiple astronaut flights, complex robotic operations, technically demanding research missions and Canadians in key leadership roles at NASA, Canadarm and Collaboration: How Canadas Astronauts and Space Robots Explore New Worlds gives Canadians fantastic insights into programs that are part of our history as well as the foundation for our international reputation as a leader in the utilization and exploration of space. It is a book that I couldnt put down in part for the memories that resurfaced while reading it, but primarily for the pride I felt to be one small part of the amazing group of Canadians who made the impossible possible. For anyone interested in space exploration, it is a must-read.

David R. Williams OC OOnt MD CM

Canadian Astronaut STS-90, STS-118

Bestselling author of Defying Limits.

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns, driven time and again off course.

Homer, The Odyssey (translated by Robert Fagles, 1996)

Nightmares about a rocket abort woke me up early on a cold Kazakhstan morning in December.

I clearly saw the scenario on this historic launch day: Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques saluting the Russian commission in his spacesuit, moments after saying goodbye to his three small children and physician wife. His cold bus ride to the launch pad at Baikonur, sitting alongside his two crewmates. A final wave to colleagues and friends gathered at the foot of the rocket.

A flawless liftoff to the International Space Station, marred by a sudden vibration. Saint-Jacques, in the left-hand pilots seat, would scan the abnormal readouts on the console. Either he or Russian commander Oleg Kononenko would speak with Russias mission control calmly, scientifically, even as their abort system pulled them violently towards Earth.

Two minutes and 45 seconds, they would say in Russian as they read the elapsed time since their rocket lifted off. They would report the emergency, the failure of the booster as the abort system took over. And they would keep astronaut-ing all the way down to the ground, doing everything possible to keep the spacecraft from crashing into the Kazakh Steppe.