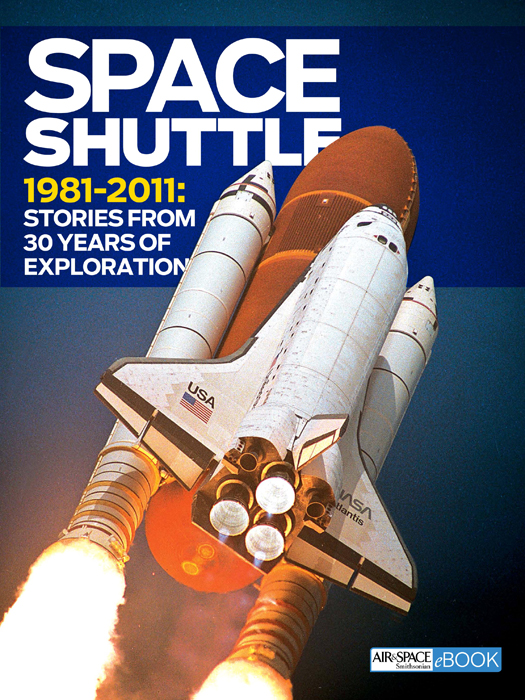

Text 2014 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use.

For information, please write:

Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books,

P. O. Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine

Magazine Editor: Linda Musser Shiner

Space Editor: Tony Reichhardt

Art Director: Ted Lopez

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Production Editor: Christina Wiginton

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen in the endnotes. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-487-8

v3.1

Foreword

Single Room, Earth View

BY SALLY RIDE

Everyone Ive met has a glittering, if vague, mental image of space travel. And naturally enough, people want to hear about it from an astronaut: How did it feel? What did it look like? Were you scared? I find a way to answer but its not easy.

Introduction

The Shuttle Generation

BY TONY REICHHARDT

Chapter 1

The Worlds First Spaceplane

The country that landed a man on the moon wanted a spaceship that could fly like an airliner.

MAIN ENGINES

BY T.A. HEPPENHEIMER

BY LINDA SHINER

SHUTTLE TILES

BY DAMOND BENNINGFIELD

Chapter 2

1980s: Steep Learning Curve

After two dozen missions, the cost of operating the space shuttle became painfully clear.

LAUNCH, LAND, LAUNCH AGAIN

BY GREG FREIHERR

SOLID ROCKET BOOSTERS

BY JAMES R. CHILES | PHOTOGRAPHS BY CHAD SLATTERY

Chapter 3

1990s: The Tempo of Success

In the 1990s, the shuttle launched planetary probes, great observatories, and a partnership with Russia.

BY GREG FREIHERR

TRAINING AIRCRAFT

BY DEBBIE GARY

Chapter 4

2000s: A Building in Space

Ten years into the new century, the space shuttle completed the mission it had been created for.

BY MICHAEL KLESIUS

FOREWORD

Single Room, Earth View

BY SALLY RIDE

As the first American woman in space, Sally Ride (19512012) was perhaps the best known of the shuttle astronauts.

EVERYONE IVE MET HAS a glittering, if vague, mental image of space travel. And naturally enough, people want to hear about it from an astronaut: How did it feel? What did it look like? Were you scared? Sometimes, the questions come from reporters, their pens poised and their recorders silently sucking in the words; sometimes, its wide-eyed, 10-year-old girls who want answers. I find a way to answer all of them, but its not easy.

Imagine trying to describe an airplane ride to someone who has never flown. An articulate traveler could describe the sights but would find it much harder to explain how the new view from a greater distance provides a difference in perspective, along with the feelings, impressions, and insights that go with that new perspective.

And the difference is enormous: Spaceflight moves the traveler another giant step farther away.

Eight and a half thunderous minutes after launch, an astronaut is orbiting high above Earth, suddenly able to watch typhoons form, volcanoes smolder, and meteors streak through the atmosphere below.

While flying over Hawaii, several astronauts have marveled that the islands look just like they do on a map. When people first hear that, they wonder what should be so surprising.

Yet for the astronauts, it is an absolutely startling sensation: The islands really do look as if that part of the world has been carpeted with a big page torn out of Rand McNally, and all we can do is try to convey that scenes surreal quality.

To Sally Ride, the view of the Hawaiian islands from orbit, appearing just as they would in an atlas, was startling.

In orbit, racing along at five miles per second, the space shuttle circles Earth once every 90 minutes. I found that at this speed, unless I kept my nose pressed to the window, it was almost impossible to keep track of where we were at any given momentthe world below simply changes too fast. If I turned my concentration away for too long, even just to grab a camera, I could miss an entire landmass. Its embarrassing to float up to a window, glance outside, and then have to ask a crewmate, What continent is this?

We could see smoke rising from fires that dotted the entire east coast of Africa, and in the same orbit only moments later, ice floes jostling one another for position in the Antarctic. We could see the Ganges River dumping its murky, sediment-laden water into the Indian Ocean and watch ominous hurricane clouds expanding and rising like biscuits in the oven of the Caribbean.

Mountain ranges, volcanoes, and river deltas appeared in salt-and-flour relief, all leading me to assume the role of a novice geologist. In such moments, it was easy to imagine the upheavals that created jutting mountain ranges and the wrenchings that created rifts and seas.

A late summer view of the snow-covered Bernese Alps in central Switzerland.

I also became an instant believer in plate tectonics; India really is crashing into Asia, and Saudi Arabia and Egypt really are pulling apart, making the Red Sea wider. Even though their respective motions are no more than mere inches a year, the view from overhead makes theory come alive.

Spectacular as the view is from 200 miles up, Earth is not the awe-inspiring blue marble made famous by the Apollo photos from the moon. From space shuttle altitude, we cant see the entire globe at a glance, but we can look down the entire boot of Italy, or up the East Coast of the United States from Cape Hatteras to Cape Cod. The panoramic view inspires an appreciation for the scale of some of natures phenomena. One day, as I scanned the sandy expanse of northern Africa, I couldnt find any of the familiar landmarkscolorful outcroppings of rock in Chad, irrigated patches of the Sahara. Then I realized they were obscured by a huge dust storm, a cloud of sand that enveloped the continent from Morocco to the Sudan.

By orbital standards the space shuttle flies fairly low (its more than 22,000 miles lower than a typical television satellite), so we can make out both natural and human-made features in surprising detail. Familiar geographical features like San Francisco Bay, Long Island, and Lake Michigan are easy to recognize, as are many cities, bridges, and airports. The Great Wall of China is not the only man-made object visible from space.