Disaster in Space!

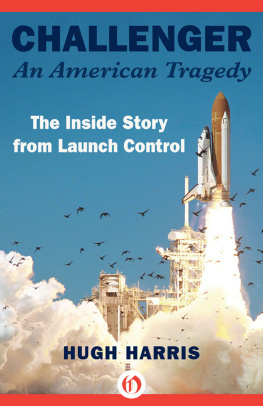

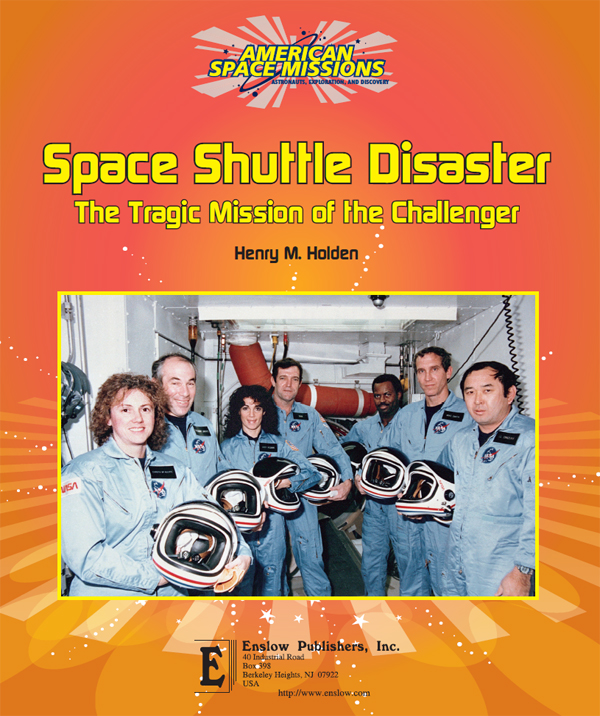

On the frigid morning of January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger rumbled off the launchpad at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Brilliant orange flames and clouds of smoke billowed out of the external fuel tank, lifting Challenger high into the crystal-blue sky. The mission had attracted worldwide attention. NASA was sending the first teacher, Christa McAuliffe, into space. Crowds gathered to watch the launch, and millions tuned in on television. But less than two minutes into the mission, Challenger exploded in midair, and the historic day ended in tragedy. Author Henry M. Holden takes an in-depth look at this space shuttle disaster.

About the Author

Henry M. Holden, with a background in the telecommunications industry, writes for children and adults. He has published several books for Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Image Credit: NASA Kennedy Space Center

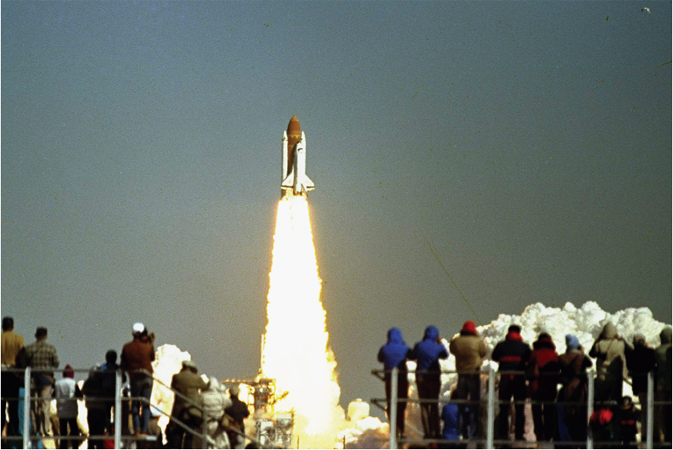

It was early Tuesday morning, January 28, 1986. The weather at Cape Canaveral was frigid. The night before, the temperature had gone below freezing. People could see icicles on the launchpad. The Florida sun was warming the air and would soon begin to melt the two-foot icicles. It was the coldest day ever for a space shuttle launch.

This launch had captured worldwide attention. It was going to carry Sharon Christa McAuliffe, a history teacher, into space. She was going to be the first passenger/observer of the Teacher in Space Program.

There were concerns in the Mission Control Center. They had asked for three ice inspections of the rockets and the shuttle Challenger. The third inspection, shortly before launch, showed the ice had melted onto the launchpad. The flight had been postponed six times due to bad weather and mechanical issues. There had been another two-hour delay earlier in the morning. A part in the launch processing system had failed during fueling.

At T-(for takeoff) minus six seconds, Challengers main engines fired. Huge billowing columns of flame and smoke surrounded the base of the shuttle. Within four seconds, the engines were burning at 90 percent power.

The launch is the most dangerous part of the flight. The external fuel tank was filled with 528,600 gallons (more than 2 million liters) of explosive fuel. They help generate 2.6 million pounds (1.7 million kilograms) of thrust.

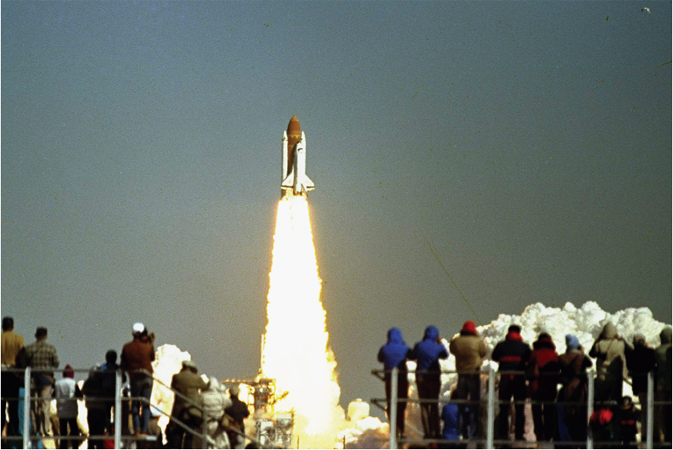

At T-minus zero seconds, the two white solid fuel rocket boosters ignited. These were attached to each side of the huge external fuel tank. Each of the boosters carried more than 1.1 million pounds (498,952 kilograms) of solid fuel. They were to help the main engines lift the shuttle to a speed of 3,512 miles per hour (5,652 kilometers per hour). The shuttle roared off the pad and into the sky. Five miles (8 kilometers) away, hundreds of spectators could feel the ground shaking beneath their feet.

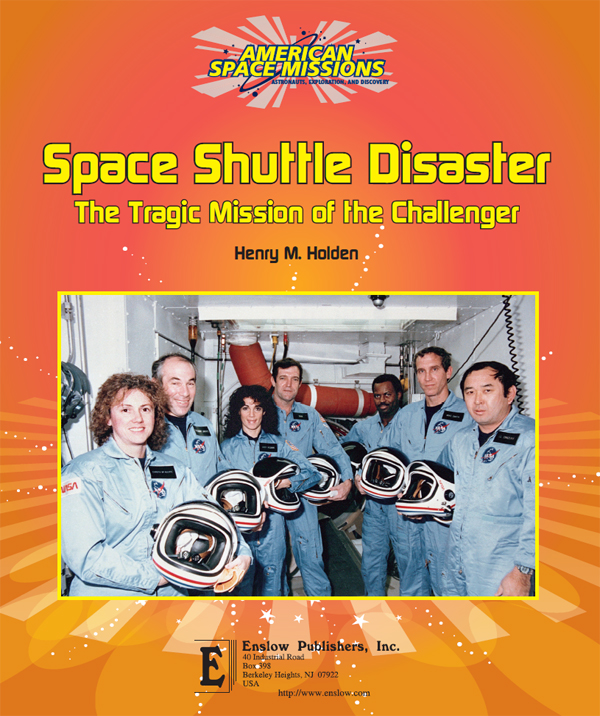

Liftoff occurred at 11:38 A.M. The rockets boosted the shuttle off the launchpad. Challenger arched up through the air, leaving a thick trail of smoke behind. This was Challengers tenth mission. McAuliffe and the crew, commander Francis Dick Scobee, pilot Michael J. Smith, and mission specialists Judith A. Resnik, Ellison S. Onizuka, Ronald E. McNair, and Gregory B. Jarvis, awaited the upcoming mission.

For the first sixty seconds, all systems seemed to work perfectly. At T-plus seventy seconds, Mission Control told Commander Scobee to throttle up. This means the pilot increases the speed of the shuttle. Three seconds later, Smith said, uhh... oh!

Image Credit: AP Images / Bruce Weaver

Spectators watch the space shuttle Challenger lift off from Kennedy Space Center on January 28, 1986. After the first sixty seconds of the launch, all systems seemed to work well.

Image Credit: NASA Kennedy Space Center

Millions of people around the world watched the Challenger explode just seventy-two seconds into the launch. This photo, taken a few seconds after the accident, shows exhaust plumes from the shuttles main engines and the solid rocket booster entwined around a ball of gas from the external fuel tank.

Millions of people were watching on television. Due to the fact that McAullife was on board, thousands of schoolchildren were part of this audience. They were following the thick white vapor trail behind the shuttle. At 58.8 seconds into the flight, a flame, later seen on enhanced film, was coming from the right solid rocket booster. At 72 seconds, there was a sudden chain of events that destroyed Challenger and the seven crew members on board. All these events happened in less than two seconds. A huge white cloud formed where the shuttle had been. From within the white cloud came a horrific flaming ball of fire.

Moments before, people had been filled with joy. Now no one could believe what he or she had just seen. The rocket had blown to pieces. It was the worst tragedy in the history of the space program.

Perhaps not until the attack on the World Trade Center towers, on September 11, 2001, did American children and adults have such a terrible feeling inside as they did when they watched the destruction of Challenger. Sadly, this would not be the last time the world would watch a space shuttle tragedy. On February 1, 2003, the shuttle Columbia broke apart on reentry into Earths atmosphere.

Image Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

The space shuttle Challenger in Earth orbit in 1983. This was the second space shuttle that NASA built, and it joined the fleet in 1982.

Challenger was the name of the orbiter that was to carry the astronauts into space. It was attached to a large orange external fuel tank and two solid rocket boosters. It was the second shuttle built, and it had joined the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) fleet in 1982. It was named for a ship that explored uncharted ocean waters a century earlier.

Challenger STS (flight) 51L was scheduled to launch in July 1985. However, by the time the crew was assigned, the launch had been postponed to November. The Challenger launch was now behind schedule. Challenger was finally rescheduled for launch in late January. The pressure was on NASA. Additional delays would have a negative effect on the coming shuttle launches. They, too, would have to be postponed.

On Monday, January 27, the Florida temperatures began to drop. At night, they dipped to 24F (4C) at the launch site. The wind chill factor made it feel as if it were 10F (23C). At dawn, the temperature began to rise slowly. Engineers from the company that built the solid fuel rocket boosters were very worried. They had experience with launches in cold weather. It could be dangerous to the astronauts. On earlier flights, some rubber seals, called O-rings, within the solid rocket boosters suffered damage from superheated gases. The damage had occurred at launch temperatures much higher than on this day. Up to that time, the lowest launch temperature had been 53F (11.7C). However, because the engineers could not show positive proof that the launch could be dangerous, NASA decided to launch