Pressure

Managers and engineers at NASA had seen the warning signs on previous shuttle launchesburn marks where sections of the (SRBs) joined together. Pressure had caused rocket fuel to leak through parts of the joints. They knew the leaking might happen again. They knew it could cause a massive catastrophe. And they knew the cold weather that day could increase the risk.

But so far, through 24 previous space shuttle missions, the burns had done no real harm. Nothing had actually gone wrong.

NASA felt intense pressure to keep flying. Throughout the early 1980s, the space shuttle program had been struggling. It was taking longer than expected to prepare shuttles to fly again after they returned. Various problems with the shuttles caused delays, increased costs, and spawned concerns over safety. NASA was embarrassed. And it was worried. If the government lost confidence in the space shuttle program, it would stop paying for it. NASA needed to show that it could keep up the schedule.

When it came to the Challenger launch, there was another source of pressure. One of the astronauts was Christa McAuliffe, who was to be the first Teacher in Space. As the first civilian to fly into space, McAuliffe was an important symbol. She showed that the space shuttle could allow ordinary people access to outer space. That was exactly what NASA wanted people to think about the shuttle programnot delayed launches and wasted money.

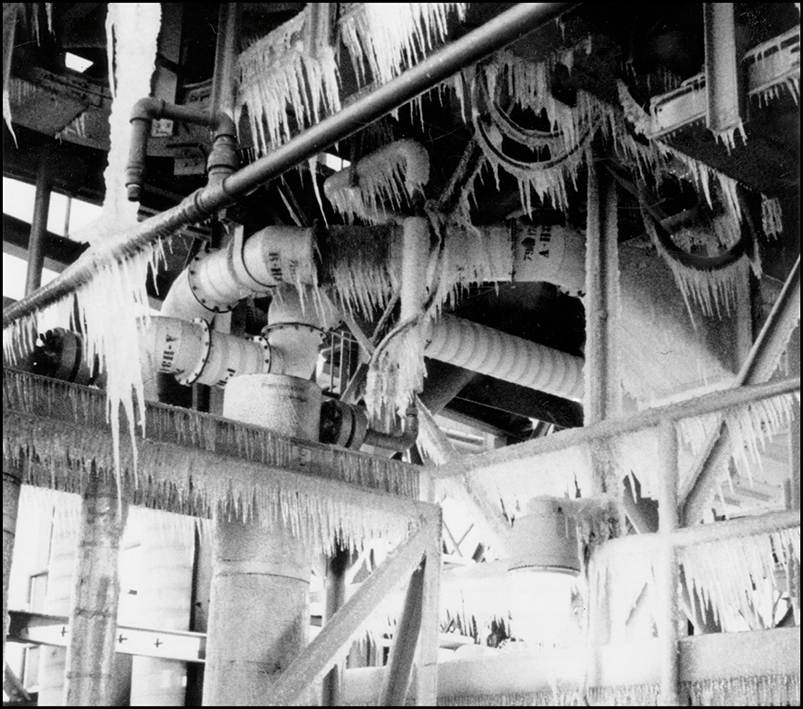

Only things werent going as planned. The weather had been much colder than it usually is in Florida. There was ice on the launchpad. By January 28, 1986, Challengers launch had been delayed four times, and engineers pleaded for it to be delayed again.

Instead, Challenger lifted off into the cold, blue sky.

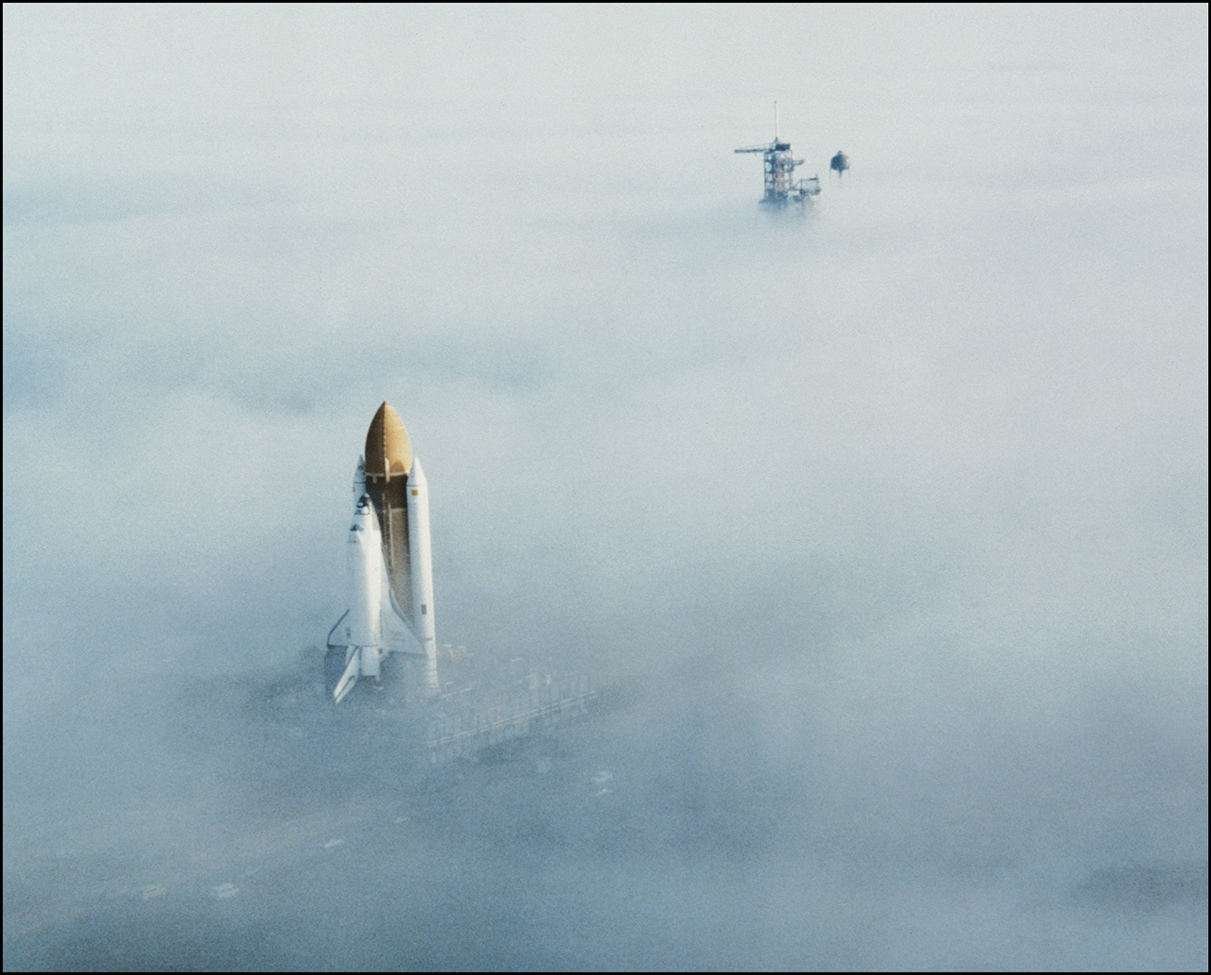

The space shuttle Challenger, with its two white solid rocket boosters near the wings, traveled through early morning fog on its way to the icy launchpad for its 10th launch.

Allan McDonald

Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, January 27, 1986, about 10:50 p.m.

The more time passed, the more Allan McDonald worried.

His bosses at Morton Thiokolthe company that made the space shuttles solid rocket boostershad requested a five-minute break from the group phone call they were having. They wanted to have a private discussion. But now it had been nearly 30 minutes, and still Thiokol was off-line.

The question they were discussing was complicated because there were many factors to consider. And yet it was very simple. Should Challenger launch tomorrow?

The answer, McDonald knew, was No. It shouldnt. The Thiokol engineers had just spent two hours on the phone explaining the dangers. They believed it was too risky to launch when the temperature was going to be so cold. So why did the Thiokol managers want to talk in private? And what was taking so long?

The three-way conference call involved the Thiokol people in Utah, NASA people at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Alabama, and NASA people at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. McDonald worked for Thiokol, but he was at KSC with the NASA managers. Outside the meeting room there, Challenger sat on its launchpad, nose pointed into the sky, glowing in the white light of high-powered lamps. Each of the two massive solid rocket boosters attached to the bottom were filled with 500 tons of solid fuel. Between those sat an even bigger vessel, the external fuel tank for the shuttles main engines, which would be filled with 143,000 gallons of liquid oxygen and 383,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen.

As the director of the SRB project at Thiokol, it was McDonalds job to represent his company at KSC and give a yes or no to the shuttles launch. For this launch, when it would get as cold as 18 degrees, McDonald knew there might be a problem with the SRBs. Thats why he arranged the conference call with Thiokol. He wanted to hear what the engineers thought. They were the experts. They knew more about the SRBs than anyone else. McDonald planned to do whatever the engineers recommended.

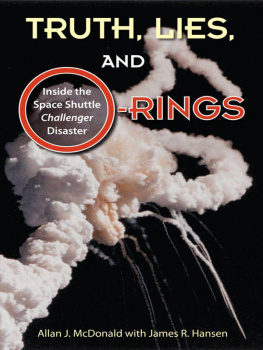

According to the engineers, the danger had to do with the O-ringsrubber rings that helped seal the sections of the SRBs together. After previous shuttle flights, they had found evidence of blowbysoot outside the primary O-rings. This meant that the O-rings had not made a perfect seal, and some rocket fuel had blown through, leaving burns. Luckily, the secondary O-rings had always held and nothing terrible had happened. But if a leak was bad enough, an explosion could occur.

The worst blowby came on a launch one year earlier, when the temperature was 53 degreesthe coldest shuttle launch ever. Thiokol engineers had evidence that the O-rings tended to get stiff in cold temperatures and not hold their seals as well. Over the course of the two-hour phone call, they had described this evidence. They had faxed over charts and photos showing burn marks.

Thiokol engineer Roger Boisjoly described most of the evidence. He had a reputation for being a whip-smart problem solver.

The colder temperatures predicted can change the O-ring material from something like a hard sponge to something like a brick, Boisjoly said on the phone.

But NASA pushed back. Lawrence Mulloy, the SRB project manager for NASA, asked Boisjoly and his colleagues if they knew the cold weather affected the seals. He said the evidence showed that blowby had occurred on launches of different temperatures, including warm-weather launches.

The engineers admitted that was true.

How then can you conclude that temperature has anything to do with blowby? asked Mulloy.

Boisjoly didnt back down. He said the blowby was worse when the weather was colder. McDonald, sitting at the table with Mulloy, noticed that this answer seemed to make Mulloy angry.

Mulloy then asked Joe Kilminster, one of the Thiokol vice presidents on the call, Whats your recommendation?

We recommend no-go, Kilminster said.

My God, Mulloy shouted. When do you want me to launch, next April?

McDonald saw determination burning in Mulloys eyes. He realized that NASA wanted to launch tomorrow no matter what. He couldnt believe it.

Even without seeing Mulloy in person, Kilminster also understood his determination to launch. Thats when he asked for the five-minute break.

Maybe theyre going to try to find more evidence to support the no-go, thought McDonald.

But the longer the break lasted, the more he worried they were going to give in.

Roger Boisjoly

Offices at Morton Thiokol in Utah, during the break

In Utah the private discussion among Morton Thiokol employees had taken a new turn.

We need to make a management decision, said Jerry Mason, the highest-ranking vice president in the room.

Roger Boisjoly knew what that meant. The engineers opinion would be downplayed. Managers had to think about keeping their customerNASAhappy. NASA had been paying Thiokol millions of dollars to build the SRBs. But in the previous few months, it had talked about using another company instead. If NASA was unhappy with the job Thiokol was doing, it might start buying its rocket boosters from another provider.