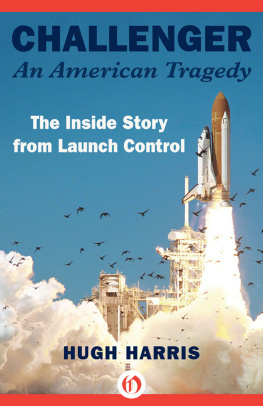

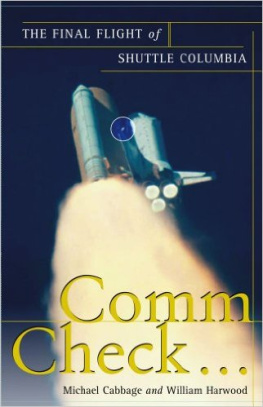

Challenger: An American Tragedy

The Inside Story from Launch Control

Hugh Harris

This book is dedicated to my wife, Cora; the Challenger crew; and the family of tens of thousands of people who worked so hard to make the space shuttle program the success it was.

Chapter One: A Look Back Twenty-eight Years

Challenger was a spacecraft designed to transport, protect, and nurture its seven-member crew as it transported them beyond the limits of our home planets life-support system. There, they would conduct experiments to improve lives on Earth. Among its passengers was the first civilian crewmember, the Teacher in Space Sharon Christa McAuliffe (known as Christa), who was already inspiring a generation of school children.

I had watched from the firing room as the twenty-four previous shuttles rocketed upward and successfully returned to Earth. But on January 28, 1986, Challenger was engulfed in a fiery inferno in full view of thousands of people at the center and millions of others viewing the launch on television.

The tragedy produced a myriad of human emotions. For Todd Halvorson of Florida Today, it was an unforgettable introduction to space reporting. Hired the day before, but not yet on the job, he stepped out of the Cocoa Beach Holiday Inn to watch. Burned into his psyche are the pitchfork contrails and the memory of a weeping young girl, pointing upward and crying over and over, The teacher is up there! The teacher is up there!

For some young astronauts, it was a loss of innocence that took some time to accept. Franklin Chang-Daz flew on STS-61C, the shuttle mission just a few weeks before Challenger. He and his crew experienced the tragedy from a viewing room at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

I think we were all unprepared to deal with this kind of event, he says. From my first flight before the Challenger disaster, to my second flight, after, it felt as if we had lost our innocence. When I went into my second flightwell, it was probably the same way a soldier goes into battle with a few scars. You dont look at that battlefield the same way you did on the first day. I mean, it was still exciting, it was still wonderful, but we realized it was not childs play anymore.

Lisa Malone, then a young public information specialist who would become director of public affairs for the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) twenty years later, recalled, At the time, I was angry. I was angry at the engineers. I didnt yet realize how hard space flight was. Later, as I started to go to more technical meetings, I learned the difficulty of managing risk posed by a highly complex vehicle.

The accident triggered in-depth investigations and denied the nation of human access to space for almost three years. Unmanned launches continued, but our astronauts stayed on the ground.

It brought into question the way management and technical experts worked together. It highlighted the role played by political decisions and uncertain year-to-year funding. It exposed the roadblocks to communication imposed by managers and organizational culture.

It was a chilling reminder that it is safer to sit on the ground than fly into space. But thats not an option for the human race.

Ultimately, it helped enable 110 more space-shuttle flights and the construction of the International Space Station, which ranks near the top of human achievement.

Dozens of people gave the go to launch on that morning twenty-eight years ago, and tens of thousands more had worked on the hardware. Yet, despite all of the investigative probing and some rancorous finger-pointing in the months to follow, no one ever alleged less than a strong desire to do his or her job to the best of his or her ability.

It demonstrated, once again, how much there is to learn as humankind continues to advance the boundaries of science, technology, and human interaction.

On that day, I was the chief of public information for NASAs Kennedy Space Center and the launch commentator. This piece will take you on the same journey I experienced in the hours before launch and then along the bumpy road to find the cause of the accident and heal the system.

Chapter Two: A Cold, Cold Night

The night of January 28, 1986, was the coldest I can remember in Florida. But when I left my house in Cocoa Beach at two a.m., I wasnt thinking of the cold. I was worrying about getting to the Kennedy Space Center on time.

Every time I served as the voice of launch control for a space shuttle launcha responsibility I had held beginning with STS-1 in 1981I worried that my car would be delayed by the hundreds of thousands of people who came to watch. If I didnt get to the firing room on time, the launch would have happened anyway, but I would have felt like Id let down the team.

But this morning, as I drove toward KSC, I did not find the usual congregation of cars. Very few were parked along the causeway over the Banana River. Normally, even at that early hour in the morning, and eight or more hours before a launch, the causeways were crowded. Families would leave their cars to make new friends or gather around radios to keep track of the progress of launch preparations. Cars would sport license plates from dozens of statesCalifornia, Washington, even Alaska. The space program was a source of national pride, and we who were privileged to work in it could not help but be inspired.

But this night was different. The few who had come were huddled inside their vehicles.

In the distance, Pad 39 B and Challenger were sparkling in the pure white light of the xenon searchlights. The thick shafts of light illuminated the rocket vehicle and slanted skyward for many miles.

As I drove toward the center along State Route 3 on Merritt Island, some of the orange groves huddled under blankets of smoke from large bonfires created to help protect the fruit from freezing. Most of the large groves had been flooded or sprayed with water. The temperature of fruit encased with ice does not drop below freezing. Smudge pots were no longer used due to pollution.

The air temperature was in the low thirties and dropping rapidly into the twenties. The smaller grove owners could not afford to protect their groves, and a week later their oranges would be thudding to the ground at the rate of a dozen per minute.

The officers at the first guard gate wore heavy jackets. Do you think it will go, Mr. Harris? one asked.

I told them the launch had already been postponed an hour and might be delayed further because of concern due to the cold. I said, Theyre supposed to start tanking around three a.m. If they tank, theyll try to launch. They have about a two-hour window.

In capitulation to the freezing cold, the press site looked pretty deserted when I arrived. Normally, the photographers and reporters would be walking between buildings or gathered in little groups for a smoke. This morning they were all indoors.

There were fewer press representatives than normal, as well. The shuttle launches had become routine through the years. About five hundred media had been accredited for Challengeras opposed to five times that number for STS-1. As I recall, only one of the major networks was covering the launch live.

The science writers typically on hand for launch had a conflict this time. Press briefings were taking place at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, where many of the most knowledgeable space reporters were learning what scientists were discovering as

Next page