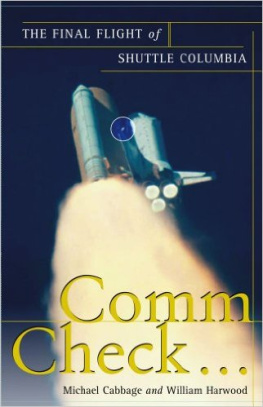

COMM CHECK

THE FINAL FLIGHT OF SHUTTLE COLUMBIA

Michael Cabbage and William Harwood

FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2004 by Michael Cabbage and William Harwood

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole

or in part in any form.

All photographs unless otherwise noted are courtesy of NASA

Free Press and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales:

1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com

Designed by Joseph Rutt

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 0-7432-6091-0

ISBN-13: 978-1-439-10176-6

eISBN-13: 978-0-743-26698-7

To Mom and Dad

Michael Cabbage

To the memory of Brian Welch

William Harwood

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

From Michael Cabbage: I would like to thank Orlando Sentinel publisher Kathy Waltz, editor Tim Franklin, and managing editor Elaine Kramer for making it possible for me to write this book and consistently supporting aerospace reporting as few others in American journalism; Bob Shaw, Alex Beasley, Sal Recchi and Sean Holton for their editing guidance, help and advice in the days and weeks following the disaster; fellow reporters and photographers on the Sentinels Columbia coverage team, including Gwyneth Shaw, Robyn Suriano, Kevin Spear, Jim Leusner, Red Huber, Debbie Salamone, Dan Tracy, Jeff Kunerth, Scott Powers, Rene Stutzman, Pam Johnson, Mary Shanklin, Anthony Colarossi, Mike McLeod and Sean Mussenden, whose hard work helped uncover some of the events and issues described in this book; and special thanks to Sal Recchi and Ann Hellmuth for their friendship and moral support in the weeks following the accident. Thanks also to senior editor Craig Covault of Aviation Week and Space Technology magazine, another friend whose input was invaluable. And last but certainly not least, my thanks, love and eternal gratitude to my neglected wife, Lori, and children, Elizabeth and John, without whose love and support this book could not have been written.

From William Harwood: I would like to thank CBS News President Andrew Heyward, Al Ortiz and Mark Kramer for their long-standing commitment to covering the space program and for giving me time off to write this book. Special thanks also go to correspondent Sharyl Attkisson and her husband, Jim, for providing much-needed advice and moral support; and to Washington correspondent and aviation expert Bob Orr and producer Ward Sloane for going the extra mile to get the facts straight. Orrs perspective from long experience with past disasterscomplex systems fail in complex waysproved invaluable. Special thanks also to CBS Radio correspondent Peter King for his unfailing politeness and cheerful demeanor while holding the ravenous radio beast at bay; to Steven Young and Justin Ray of Space flightnow.com; and to Kathy Sawyer and Nils Bruzelius of The Washington Post. Finally, this project would not have been possible without the loving encouragement of my wife, Catherine, and our children, Houston and Riley. And of course, my parents, Kate and Walter Harwood, who taught me to wonder about the universe.

We would both like to thank our agent, Gail Ross, and our editor, Bruce Nichols, for their patience and encouragement. From NASA public affairs, thanks to Glenn Mahone and Bob Jacobs at NASA Headquarters, Johnson Space Centers James Hartsfield, Rob Navias and Kyle Herring, who arranged countless interviews, June Malone at the Marshall Space Flight Center, and Mike Rein and Bill Johnson at the Kennedy Space Center; Special thanks to Laura Brown of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board for providing technical feedback and setting up interviews; Kari Allen of Boeing; Mike Curry of United Space Alliance; Traci Lutter at Far Out Transcription Services; Phyllis Cabbage and Judy and David Mitchell for their Southern hospitality during six hectic weeks in Knoxville; the faculty of the University of Tennessee School of Journalism for their help and advice, past and present; and Charlie at The Tap Room, a friend to us and other wayward college students for more than a quarter-century.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

After seeing more than 40 shuttle landings, Orlando Sentinel space editor Michael Cabbage knew something was wrong.

Like other reporters at the Kennedy Space Centers shuttle runway, he had arrived an hour before Columbias scheduled touchdown expecting a routine end to the 16-day flight. In fact, the handful of people who turned up at the landing strip that Saturday morning, Feb. 1, 2003, were more preoccupied with afternoon activities like yard work, sports events and cookouts than the return of the years first shuttle mission.

But Cabbage had a sinking feeling. About 12 minutes remained before Columbias 9:16 a.m. landing and Mission Control did not know where the shuttle was. Momentary comm dropouts were not unusual, but Columbias crew had been out of contact with flight controllers in Houston for five long minutes. And that never had happened before.

As Cabbage watched a NASA television broadcast at the landing strip, he noticed something else peculiar: A red triangle used to show Columbias progress across a map of North America had stopped moving over central Texas. That had to be a glitch, he thought. Moments later, his pager went off.

Cabbage ducked into a nearly-deserted public affairs center at the runways mid-point to return the call. It was Robyn Suriano, another Orlando Sentinel reporter, who was monitoring the landing from the newspapers bureau at Kennedys press site.

They cant contact the crew, Suriano said. Should we be worried?

I know, Cabbage replied. This isnt good.

As Cabbage spoke at a desk in the rear of the building, a voice suddenly boomed out of a nearby speakerphone dialed into an internal public affairs teleconference. He instantly recognized the voice of Kyle Herring, a public affairs officer at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

All of the sensors that dropped off before we lost contact were in the left wing, Herring said. There are reports online of debris over Texas. Were getting ready to lock the doors and declare a contingency.

This cant be happening, Cabbage thought. Herrings terse comments meant flight controllers believed the shuttle and its crew were lost.

At the CBS News bureau a mile from the shuttle runway, William Harwood was putting the finishing touches on a post-mission wrap-up story he planned to post to the networks website within minutes of Columbias touchdown. As always on landing day, Harwood was in the bureaus second-floor television studio, wired up and prepared to go on the air in the event of a disaster. But CBS had no plans to interrupt its Saturday morning news show for an uneventful landing and Harwood, a veteran of 107 of the 113 shuttle missions to date, did not expect any problems.

Space shuttle re-entries did not generate the same level of nervous anticipation as launches and Harwood was listening to Mission Control with, quite literally, half an ear. One of his two earpieces was plugged into a network audio loop in New York while the other was plugged into NASAs Mission Control circuit.

Next page