Dixon - A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants

Here you can read online Dixon - A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Grande-Bretagne;Great Britain, year: 2017, publisher: Pelagic Publishing, genre: Children. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants

- Author:

- Publisher:Pelagic Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- City:Grande-Bretagne;Great Britain

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Britains Rarest

Plants

Published by Pelagic Publishing

www.pelagicpublishing.com

PO Box 725, Exeter, EX1 9QU, UK

A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants

ISBN 978-1-78427-146-6 (Pbk)

ISBN 978-1-78427-147-3 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-78427-149-7 (PDF)

Chris Dixon, 2017

Chris Dixon asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Apart from short excerpts for use in research or for reviews, no part of this document may be printed or reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, now known or hereafter invented or otherwise without prior permission from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

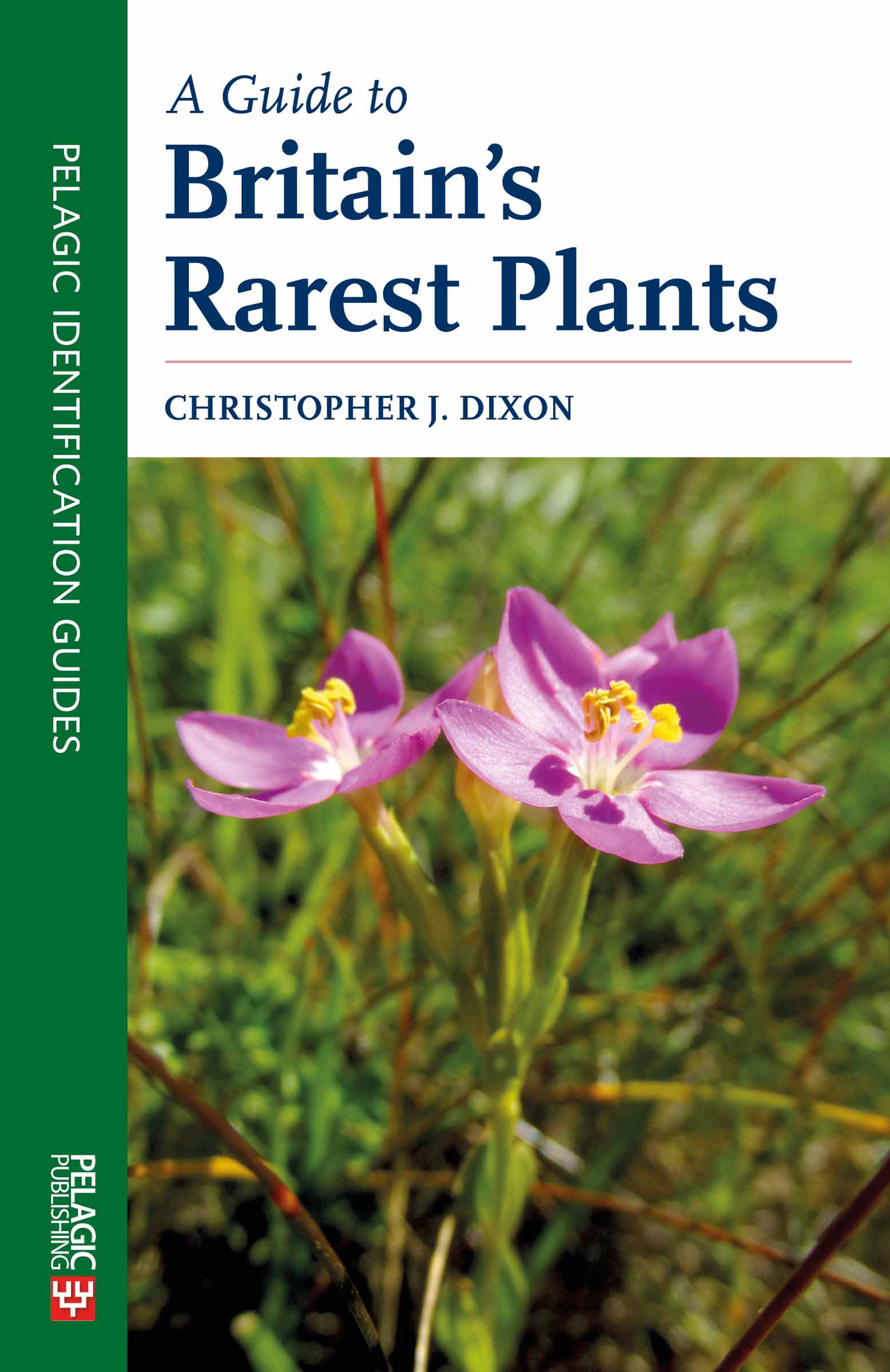

Cover photograph: Perennial centaury, Centaurium scilloides

Species (ordered alphabetically by scientific name)

The flora of the British Isles is exceptionally well studied, largely through the efforts of a small army of enthusiastic amateurs. By recording every species that occurs in each cell of a grid drawn across Great Britain, Ireland and adjacent islands, comprehensive maps have been compiled and revised, showing the range of each species. The most-used grid is at the scale of 10 km 10 km squares, but similar work is being carried out at the scale of 2 km 2 km grid squares, and even 1 km 1 km squares. For the vast majority of species, their current and past distributions are therefore known to a very high degree of accuracy, enabling detailed assessments to be made of any changes in distribution due to changes in land use or climate.

At the same time, the urban population has continued to increase, and knowledge of the natural world has continued to decline. A 2013 survey by the Woodland Trust found that 43% of adults could not recognise an oak leaf, and only around one in six could recognise an ash leaf. If that is the case for two of our most abundant and distinctive trees, then knowledge of smaller and rarer species must be far scanter. Despite the need for biologists to know which species is which in order to study them at all, natural history is hardly taught in universities any more. Knowledge of natural history is rapidly fading among both professionals and the general public.

On a global scale, Britain is no biodiversity hotspot it doesnt have the exceptional diversity of a tropical rainforest or the South African fynbos but it is still unquestionably diverse. There is a huge range of habitats, from salt-marshes to meadows, woodlands to high-mountain crags. Of the 3,000 or so plant species in the British Isles, many are well known, but there are others that you may never have heard of.

While some plants grow almost everywhere across the region, others are found at only a small handful of sites. Plants with restricted distributions can be a source of local pride. Several of the species in this book were chosen to represent their counties in Plantlifes County Flowers programme, for instance. Rare plants such as these are often held to be particularly special. Unless you go specifically looking for them, you are very unlikely to come across one. Many of our rarest plants are hard to spot in the first place, or are difficult to distinguish from similar species once theyve been found. For most of them, Britain is only part of their overall range, but in a few cases, this is all theyve got. In every case, there is a story to tell. (How did the species arrive in Britain? Why has it dwindled to so few sites? How can we ensure it survives?) In telling the story of Britains rarest plants, we are telling the story of Britains natural world, the turmoil it has faced in the past, and the challenges it will meet in the future.

The first challenge in presenting a work like this is to decide which plants to include. Any such list is to some degree arbitrary, and this book is no exception. The species here are limited to vascular plants (ferns, conifers and flowering plants, including grasses and sedges, but no mosses or seaweeds) that are generally considered to be native to Scotland, England or Wales. It is not always easy to tell which species are native (i.e. naturally occurring) and which are introduced (only present through human actions), and some instances where there is a significant possibility of human interference have been excluded. (In general, native species are expected to have a fairly stable distribution, to occur in natural habitats, especially those far from habitation, and so on; introduced species are more likely to suddenly expand or contract their ranges, and to occur predominantly in artificial habitats close to human habitation.) These include the lesser tongue-orchid (Serapias parviflora), which grew on a Cornish cliff-top for several years, and the interrupted brome (Bromus interruptus), which has become extinct in the wild.

Population estimates are hard to produce accurately, particularly given that plants can spread vegetatively, making it unclear how many separate plants are present in a population. It is therefore more reliable to use a proxy measure of rarity. This book covers a total of 66 species that are native to Britain and each of which is found in no more than three 10 km 10 km grid squares out of the nearly 3,000 that cover England, Wales and Scotland.

Rare subspecies of more widespread species have also been left out; these include the English sandwort (Arenaria norvegica subsp. anglica), the South Stack fleawort (Tephroseris integrifolia subsp. maritima) and our endemic subspecies of the common mouse-ear (Cerastium fontanum subsp. scoticum), to name just a few examples. In each of these cases, another subspecies of the same species is more widespread, meaning that the species as a whole is not rare enough to be included.

Some plants undergo a process known as apomixis, whereby offspring are almost always produced asexually. The usual definition of a species doesnt really apply in these cases, and their reproductively isolated groups known as microspecies or agamospecies are large in number but generally hard to distinguish from their relatives. In order to assign a particular plant to a microspecies, it is often necessary to consider the variation within the wider population, because there is so much overlap between similar microspecies. These critical groups, containing numerous barely distinguishable taxa, include the brambles (Rubus spp.), ladys-mantles (Alchemilla spp.), whitebeams (Sorbus spp.), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), sea-lavenders (Limonium spp.), eyebrights (Euphrasia spp.) and dandelions (Taraxacum spp.). I have not described the many rare microspecies in detail in the main part of the book, but there is a short discussion of each of the critical groups towards the end.

I have tried to include some indication of how each of the species differs from its nearest relatives in the area. These descriptions are necessarily sketchy, and can never be enough for formal identification. Anyone who wants to identify the plants they find with greater certainty should invest in a good field guide; Staces

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants»

Look at similar books to A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Guide to Britains Rarest Plants and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.