The universe is built on a plan the profound symmetry of which is somehow present in the inner structure of our intellect.

PAUL VALRY

Midday, 26 August, the Sinai Desert

Its my 40th birthday. Its 40 degrees. Im covered in factor 40 sun cream, hiding in the shade of a reed shack on one side of the Red Sea. Saudi Arabia shimmers across the blue water. Out to sea, waves break where the coral cliff descends to the sea floor. The mountains of Sinai tower behind me.

Im not usually terribly bothered by birthdays, but for a mathematician 40 is significantnot because of arcane and fantastical numerology, but because there is a generally held belief that by 40 you have done your best work. Mathematics, it is said, is a young mans game. Now that I have spent 40 years roaming the mathematical gardens, is Sinai an ominous place to find myself, in a barren desert where an exiled nation wandered for 40 years? The Fields Medal, which is mathematics highest accolade, is awarded only to mathematicians under the age of 40. They are distributed every four years. This time next year, the latest batch will be announced in Madrid, but I am now too old to aspire to be on the list.

As a child, I hadnt wanted to be a mathematician at all. Id decided at an early age that I was going to study languages at university. This, I realized, was the secret to fulfilling my ultimate dream: to become a spy. My mum had been in the Foreign Office before she got married. The Diplomatic Corps in the 1960s didnt believe that motherhood was compatible with being a diplomat, so she left the Service. But according to her, theyd let her keep the little black gun that every member of the Foreign Office was required to carry. You never know when you might be recalled for some secret assignment overseas, she said, enigmatically. The gun, she claimed, was hidden somewhere in our house.

I searched high and low for the weapon, but theyd obviously been very thorough when they taught my mum the art of concealment. The only way to get my own gun was to join the Foreign Office myself and become a spy. And if I was going to look useful, Id better be able to speak Russian.

At school I signed up for every language possible: French, German and Latin. The BBC started running a Russian course on television. My French teacher, Mr Brown, tried to help me with it. But I could never get my mouth around saying hello zdravstvuyte and even after eight weeks of following the course I still couldnt pronounce it. I began to despair. I was also becoming increasingly frustrated by the fact that there was no logic behind why certain foreign verbs behaved the way they did, and why certain nouns were masculine or feminine. Latin did hold out some hope, its strict grammar appealing to my emerging desire for things which were part of some consistent, logical scheme and not just apparently random associations. Or perhaps it was because the teacher always used my name for second-declension nouns: Marcus, Marce, Marcum,

One day, when I was 12, my mathematics teacher pointed at me during a class and said, du Sautoy, see me at the end of the lesson. I thought I must be in trouble. I followed him outside, and when we reached the back of the maths block he took a cigar from his pocket. He explained that this is where he came to smoke at break-time. The other teachers didnt like the smoke in the common room. He lit the cigar slowly and said to me, I think you should find out what mathematics is really about.

I dont quite know even now why he singled me out from all the others in the class for this revelation. I was far from being a maths prodigy, and lots of my friends seemed just as good at the subject. But something obviously made Mr Bailson think that I might have an appetite for finding out what lay beyond the arithmetic of the classroom.

He told me that I should read Martin Gardeners column in Scientific American . He gave me the names of a couple of books which he thought I might enjoy, including one called The Language of Mathematics , by Frank Land. The simple fact of a teacher taking a personal interest in me was enough to spur me on to investigate what it was that he found so intriguing about the subject.

That weekend my dad and I took a trip up to Oxford, the nearest academic city to our home. A little shopfront on The Broad bore the name Blackwells. It didnt look terribly promising, but someone had told my dad that this was the Mecca of academic bookshops. Entering the shop you realized why. Like Doctor Whos Tardis, the shop was huge once you had entered the tiny front door. Mathematics books, we were told, were down in the Norrington Room, as the basement was known.

As we went downstairs a vast cavernous room opened up before us, stuffed full of what looked to me like every possible science book that could ever have been published. It was an Aladdins cave of science books. We found the shelves dedicated to mathematics. While my dad searched for the books my teacher had recommended, I started pulling books off the shelves and peering inside. For some reason there seemed to be a high concentration of yellow books. But it was what I found within the yellow covers that grabbed my attention. The contents looked extraordinary. I recognized strings of Greek letters from my brief foray into learning Greek. There were storms of tiny little numbers and letters adorning x s and y s. On every page there were words in bold like Lemma and Proof .

It was completely meaningless to me. There were a few students leaning against the bookshelves who seemed to be reading the books as though they were novels. Clearly, they understood this language. It was simply code for something. From that moment I decided that I was going to learn how to decode these mathematical hieroglyphics. As we were paying at the till, I saw a table full of yellow paperbacks. Theyre mathematical journals, explained the shop assistant. The publishers are offering free copies to entice academics to take out a subscription.

I picked up a copy of something called Inventiones Mathematica and put it in the bag with the books wed just bought. Here was my challenge. Could I decode the mathematical inventions in this yellow book? Some of the articles were in German, one was in French and the rest were in English. But it was the mathematical language that I was now determined to crack. What did Hilbert space and isomorphism problem mean? What message was hidden in these lines of sigmas and deltas and symbols that I couldnt even name?

When I got home I started looking at the books wed bought. The Language of Mathematics particularly intrigued me. Before our expedition to Oxford, Id never thought of mathematics as a language. At school it seemed to be just numbers that you could multiply or divide, add or subtract, with varying degrees of difficulty. But as I looked through this book I could see why my teacher had told me to find out what maths is really about.

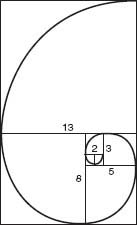

Fig. 1 How the snail uses the Fibonacci numbers to grow its shell.

In this book there was no long division to lots of decimal places or anything like that. Instead there were, for example, important number sequences like the Fibonacci numbers. Apparently, the book said, these numbers explain how flowers and shells grow. You get any number in the sequence by adding the two previous numbers together. The sequence starts 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21,The book explained how these numbers are like a code that tells a shell what to do next as it grows. A tiny snail starts off with a little 11 square house. Then, each time it outgrows its shell, it adds another room to the house. But since it doesnt have much to go on, it simply adds a room whose dimensions are the sum of the dimensions of the two previous rooms. The result of this growth is a spiral (Figure 1). It was beautiful and simple. These numbers are fundamental, said the book, to the way nature grows things.