CHAPTER ONE

Getting Acquainted with the Language

In this first chapter we profile the Japanese language to give you a basic "feel" for it. We show you how it compares with other languages, particularly English, and cover basic background such as its history and usage.

1.1 In a nutshell, what English speakers can expect

We will look later in detail at the various components of the Japanese language. But let us start off by considering in brief, and in comparative terms, some of the main features of the language as they generally strike a native English speaker. We will focus on four key areaswords, writing, grammar and usage.

1.1.1 Vocabulary

A reasonably well-educated native speaker of English will be familiar with around 25,000 words, and be able to use about two-thirds of those activelythough in typical everyday speech only around 3,000 are used.

Figures are roughly comparable for native speakers of Japanese, though they are higher by perhaps 15% or so. In general, Japanese also make a greater distinction between words actively used and those considered "bookish."

English is one of the world's richest languages, thanks to its diverse sources. The two principal sources are Romance (derived from Latin, often through French), and Germanic (including Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian). In addition we have many words from ancient Greek and numerous other sources as varied as Czech ("robot") and Arabic ("algebra"), as well as those considered ancient native such as Celtic ("crag"). In conversation around three-quarters of the words we use are Anglo-Saxon.

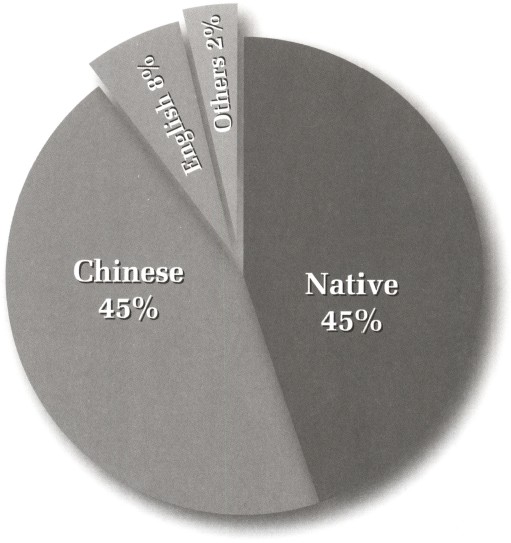

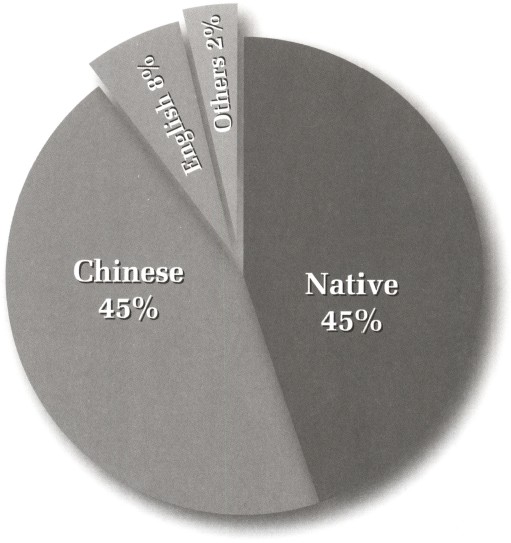

Japanese also has diverse sources. In addition to a good stock of native words, comprising almost half of all its modern vocabulary, it has a similar proportion of its words coming from Chinese, and in modern times almost ten percent of its words derive from English. Chinese plays a similar role in Japanese as Romance words in English, and in particular often has associations with classicism and learning similar to Latin and Greek. As in English, Japanese also contains a number of modified words from a variety of other languages, such as Portuguese (pan for "bread," from po), and German (arubaito for "part-time job," from Arbeit).

FIGURE 1a: Japanese vocabulary composition

1.1.2 Writing system

The English script uses the Roman alphabet of 26 symbols, effectively doubled to allow for both upper and lower case. These are used phonetically, that is to say for their sound rather than any pictorial meaning. This seems very simple. There is however a huge range in the variety of pronunciations possible for these symbols, especially in combination e.g. at least eight different ways of pronouncing "-ough" (in British English), such as in "thorough," "through," "though," "thought," "cough," "enough," "hiccough," and "bough." English spelling is among the most difficult in the world, and can be very daunting to a learner.

FIGURE 1b: Can you read this?

George Bernard Shaw is credited with illustrating the difficulty of English spelling by coming up with this spelling of a common word. What word do you think it is?

Clue: "gh" as in "enough," "o" as in "women," "ti" as in "station."

Second clue: yes, it swims in the sea!

Japanese, by contrast, can involve four different scripts. It can occasionally be written in the Roman alphabet (known as romaji), such as in textbooks or other material for foreigners or in certain advertising, but generally uses two phonetic scripts based on syllables (hiragana and katakana, collectively known as kana) in combination with characters derived from Chinese (known as kanji). Whereas phonetic scripts are based on sound, characters are based primarily on pictures or ideas, though confusingly they can in many cases also have phonetic elements and multiple pronunciations. It is this relatively complex and unfamiliar writing system, not the spoken language, that provides the major challenge for Westerners in learning Japanese to any truly advanced level.

1.1.3 Grammar

There are a number of significant differences between English and Japanese grammarthat is, the rules of language.

Whereas English is a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) language ("the dog bit the boy"), Japanese is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) ("dog boy bit"). In terms of the world's languages, there are approximately equal numbers in both categories, so it cannot be said that Japanese is unusual in this regard.

English usually relies on word-order or sometimes change of word-form to distinguish subject and object (e.g. "he" is the subject, "him" is the object), but Japanese primarily uses particles to do this. A particle is a short word (such as wa, ga or o ) that is not always translatable in itself but is used as a sort of suffix to indicate the grammatical role of the word it follows. Among other things particles can convey similar meaning to that produced in English by articles such as "the" or "a," which do not exist as such in Japanese. English has articles, Japanese has particles.

Other differences the English speaker will encounter include greater conceptual and grammatical overlap between verbs and adjectives, the frequent omission of pronouns, the frequent omission of indication of plurality or singularity, the absence of verb conjugation according to person (restricted in English relative to, say, French, but still found in "I see, she sees" and the verb "to be"), the absence of a dedicated future-only tense, the structure of subordinate clauses, and a greater sensitivity to politeness. Many of these differences boil down to Japanese generally being less explicit and specific than English.

TABLE 1a: Key grammatical differences between Japanese and English

| ENGLISH | JAPANESE |

| subject-verb-object | subject-object-verb |

| articles (a, the) | particles ( ga, wa) |

| some verb change according to person/number | no verb change according to person/number |

| dedicated future tense | no dedicated future tense |

| pronouns almost always used | pronouns often omitted |

| relative clauses follow item | relative clauses precede item |

| pronouns show subj./obj. (he/him) | pronouns unchanged |

| not especially politeness-sensitive | very politeness-sensitive |

| frequent explicitness | frequent implicitness |

1.1.4 Socio-cultural context

To a considerable extent languages reflect the cultures in which they are embedded, and in turn the particular worldview and ordering of life characteristic of that culture. In other words, as many theorists argue, your language helps shape the way you interpret the world. If there is a significant dislocation between your first language and the surrounding culture in which you find yourself, feelings of alienation can arise, as can happen with immigrants or travelers. And because both culture and language are dynamic, this feeling of alienation can even occur in your native countrythe generation gap is such an example.

Since Japanese culture is markedly different in many regards from English (or Anglo) culture, this will be reflected in language usage. What is "right" is often a matter of convention, or what anthropologists call ritual. All languages have ritualized elements, which have a socio-cultural meaning beyond or different from their literal meaning. For example, are you really enquiring about a person's state of health when you greet them with "How are you?" Similarly, when Japanese meet early in the morning (before around 10 a.m.) they will say Ohay gozaimasu meaning literally "It's early." (We will discuss the letter in Part Two.) They do not expect a reply such as "Thank you for letting me know. I hadn't realized." Such a reply would almost certainly be deemed grossly sarcastic.

![Timothy G. Stout - Tuttle More Japanese for Kids Flash Cards Kit Ebook: [Includes 64 Flash Cards, Online Audio, Wall Chart & Learning Guide]](/uploads/posts/book/417746/thumbs/timothy-g-stout-tuttle-more-japanese-for-kids.jpg)