Copyright 2016 Kathleen Dean Moore

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moore, Kathleen Dean, author.

Title: Great tide rising: towards clarity and moral courage in a time of planetary change / Kathleen Dean Moore.

Description: Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015035618

Subjects: LCSH: NatureEffect of human beings on. | Climatic changesMoral and ethical aspects. | Environmental protectionMoral and ethical aspects. | BISAC: NATURE / Environmental Conservation & Protection.

Classification: LCC GF75 .M665 2016 | DDC 179/.1--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015035618

Cover design by Gerilyn Attebery

Interior design by Megan Jones Design

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-756-5

For Zoey, Theo, and Lem.

May the world always be safe for the laughter of children.

CONTENTS

MARY EVELYN TUCKER

Yale University

W HEN WE HUMANS are lost we need directions or a map. Earlier humans had religious and cultural traditions to guide them. They provided, even imperfectly, some markers on the roadrites of passage to navigate the changing stages of life from birth to death. Those rites have become less effective as religious traditions have become somewhat diminished in the noise of infotainment. We need new guideposts to find our way amid large scale changes such as climate change and loss of species. How do we live through these most challenging times?

Kathleen Dean Moore sets out such guideposts by raising critical and challenging questions. She is resolute in her pursuit of clear answers and relentless in her moral reasoning.

Clearly, the nourishing of the human spirit and imagination is what is at stake in our present momenta spirit and imagination that is shriveling before our very eyes with an anguish and confusion that is heart rending. Kathleen bears witness. She sees how the human spirit and imagination are deeply entwined in the living forms around us. Their destruction is diminishing our capacity to dream and to hope. She worries. Without vibrant oceans and rivers, without lush quiet forests, without the movements and sounds of animals about us we will create a silence even larger than the silent spring Rachel Carson predicted. The silence will engulf us in the sound of our own lament. She weeps. This lament will not end soon for we are just beginning to write the eulogies, to sing the requiems, to plant the markers for life that is disappearing before our very eyes. And, she observes, this is true in areas that are urban and suburban, as well as rural and wild.

We are dwelling in a period of mass extinction and climate change. Loss is all around us. We are engulfed by it and at the same time we are nearly blind to it. Yet we feel in our bones some kind of unspeakable angst that will not leave us in the depths of night or even at daybreak when the birds greet the sunlight again. This crushing feeling of unstoppable destruction is holding us back from acknowledging our grief. Such loss of life demands not only mourning, but also recognition that we are in a huge historical whirlwind. Kathleen is aware that it will require every part of ourselves to find our way out. Are we like Job struggling to hear the call of life in the midst of the whirlwind of inexplicable loss? Or are we like Jacob wrestling with the angel of life in the presence of death? Or, she wonders, are we like Noah collecting and counting the animals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians that will pass through this hourglass of extinction with us?

We are groping, we are limping, we are struggling. But in this groping, in this dark night we are seeking to return to who we are. We are beings of Earth, she writes, who feel the mysterious rhythms of life unfolding. We sense this in the arc from sunrise to sunset, in the migrating patterns of birds and wild animals, in the call of whales in the depths of the oceans, in the leaping and twisting of animals and children at play, in the smell of spring soil appearing through winters snow. All of it sings to us in the movement of seasons as the planet finds its way around the sun and back again. These rhythms, she hopes, will ground us anew in the Earth that has brought forth and sustained life for billions of years. The rhythms have changed, yes, with climate change and with extinction. We are being uprooted from predictable seasonal time, yet she dares to uncover ways forward. Deep time grounds us; planetary awareness encircles us as never before.

Rediscovering who we are. Finding our purpose as humans to enhance life, not diminish it. This is her endless prayer. In this we embrace our still evolving role as children of the Earth and as a planetary species. No longer are we citizens of nations alone but of the entire globe. Our allegiance, she suggests, is moving ever outward from family, society, state, continent, to the blue green planet that is home, and even beyond to the ethics of The Cosmos. There is no time for wavering. Rather, we are ready to move carefully and humbly into our mature role as a mutually-enhancing species. To do otherwise is to risk the destruction of life on the planet, she warns.

We are currently at sea. But we know somehow that our muddling through will be crucial to finding our way back home again. Patience, courage, and endless endurance are part of this process. Maybe humor, hope, and moral clarity will steer us through the whirlwind, she muses. The lights from the shore are there if we can only come up to the deck to see them. In a dark moonless night this requires a new kind of learning of currents, of winds, and of stars for navigation. Kathleen Dean Moore offers such learning to create a compass into the future.

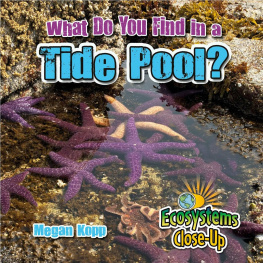

W E ARE WADING in rubber boots at the rim of the sea, my grandson and I. Behind us is a limestone ledge that shelters green anemones and limpets; in front of us, a bed of eelgrass laid flat by the receding tide. Its a silver day in Alaskashining, shivering seas and clouds so low you feel you could bump your head. My grandson leans over to poke a graying starfish.

This one is soft. Thats means its sick. This child is three years old and already he knows the signs of starfish wasting syndrome. He gives the sea star a last poke with his forefinger and stands to gaze around the cove.

His mom is around here someplace, he says, wrinkling his brow and not finding her. Hes sick. He needs a mom. I think that is undoubtedly true.

Just last year, this cove was full of sea stars. We saw them in every damp crevice, heaps of them, the purple stars, Pisaster ochraceus, and mottled stars, Evasterias troschelii, not only purple but green, red, brown, orange. This year, we come across only three or two stars, here and there, splayed on the shingle. These that remain are wasting away too, a hideous process. Lesions form. The tissues around them decay, so the sea star flattens and falls apart. An arm may crawl away, but soon it too turns to mush. Around our boots, torn arms and the wispy scraps of wasted sea stars float on the incoming tide.

Next page