To Jane, my polar star

Contents

WHY TRACK?

We were all trackers once. Ten thousand years ago our hunter-gatherer ancestors tracked for survival, while our more recent relations living in small farming communities used the skill to identify their animal neighbors. Urbanization changed many things, and the art of animal tracking seemed headed for extinction. But the pendulum now swings back, and the art and science of tracking is reemerging all over the world. Its practical value is recognized in wildlife studies, conservation biology, border patrols, and search-and-rescue operations. However, for a larger segment of the population the interest is less practicalwe are curious about our natural surroundings, and we want to know more about the animals that populate our landscapes. Tracking allows us to penetrate beyond scenic pleasure to a scientific appreciation of how nature works. Tracking is a skill anyone can learn, and it holds the power to reveal unseen eventswhich animals come and go, what they pay attention to, and how they interact with each other and with their surroundings. This book is devoted to feeding our curiosity and supporting our desire for greater connection with the natural world.

ORGANIZATION

This chapter describes the scope and regional coverage of the book, discusses how the drawings were made, defines terms, discusses basic mammal gaits, and explains the methods used for measuring tracks and gaits. The following chapters are organized by animal groups. In each chapter you will find the species treatments: drawings of tracks and scat; measurements for tracks and gaits; discussion of important identifying features; notes on habitat, scat, and other signs; and diagrams of characteristic gaits.

SCOPE AND REGIONAL COVERAGE

This book covers most of the northeastern region of the United States, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and southern and central Maine. I do not treat species like fox squirrels and lynx, which are indigenous to neighboring regions and occur only in the peripheral parts of the Northeast. Animals that are rare visitors, like cougars and gray wolves, are likewise not included in this book. The forty species covered in the book are all animals I have personally tracked, and the material presented comes from my own observations, with the exception of track and gait measurements for martens, which came from Paul Rezendess Tracking and the Art of Seeing.

DRAWINGS AND TEXT

The main content of the book consists of drawings of the tracks of adult animals. The drawings are based on photographs of real tracks, and all drawings and photographs were done by the author. Each drawing accurately depicts an actual track or combined details from two or three different tracks. The images do not attempt to show the tracks in actual size, but the relative scale of the images is consistent within each species entry. The drawings are of individual left feet, with a few exceptions: for some animals, two feet often fall together to create a distinctive form, and that form is pictured in the illustrations. For instance, a walking opossum often places its rear foot partly on top of the front from the same side, and these double impressions have a peculiar look that immediately brings to mind this specific animal. Cottontail rabbits often place their two front feet so close together the tracks coalesce into what looks like the imprint of a single, oddly shaped foot.

Each species entry also includes track and gait measurementsexplained in the following pagesand discusses key features for identification. The tracks of related animals are compared, and differences between similar tracks are described. In these discussions I refer to parts of mammalian feet, and this requires an explanation of a few morphological terms.

TRACK MORPHOLOGY

Trackers are an independent-minded lot, and there is no consensus on track terminology. I have chosen terms and definitions in the interest of simplicity and consistency, but the way I use them may differ from their use in other books. Definitions and explanations take up the rest of this chapter; they also appear in the glossary.

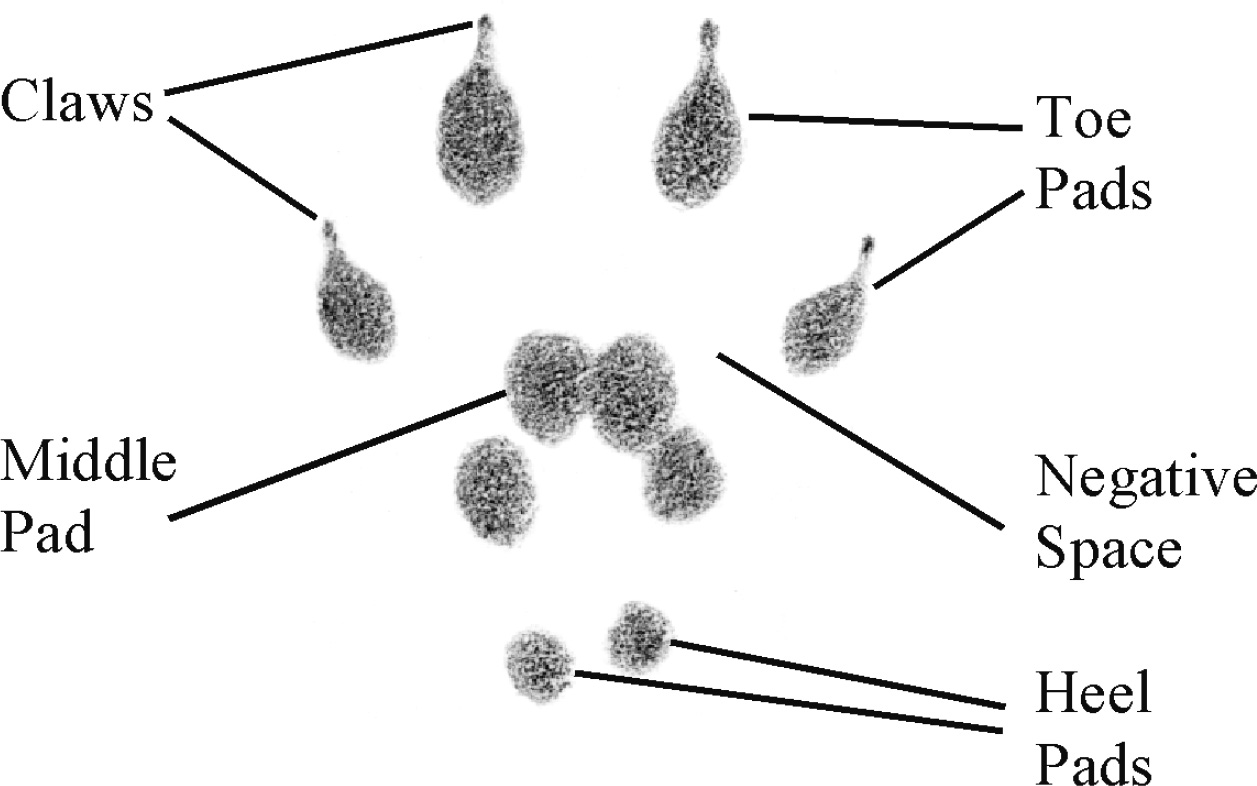

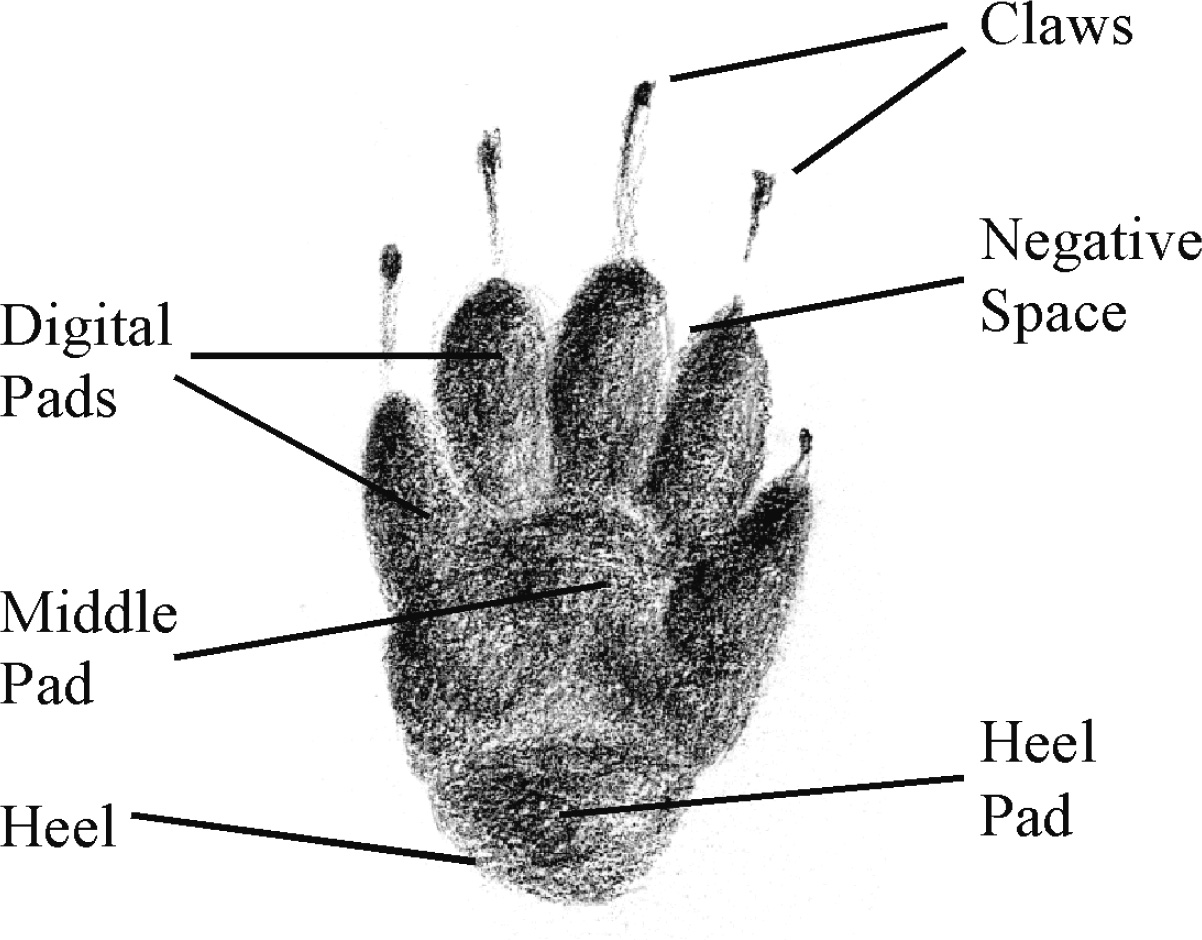

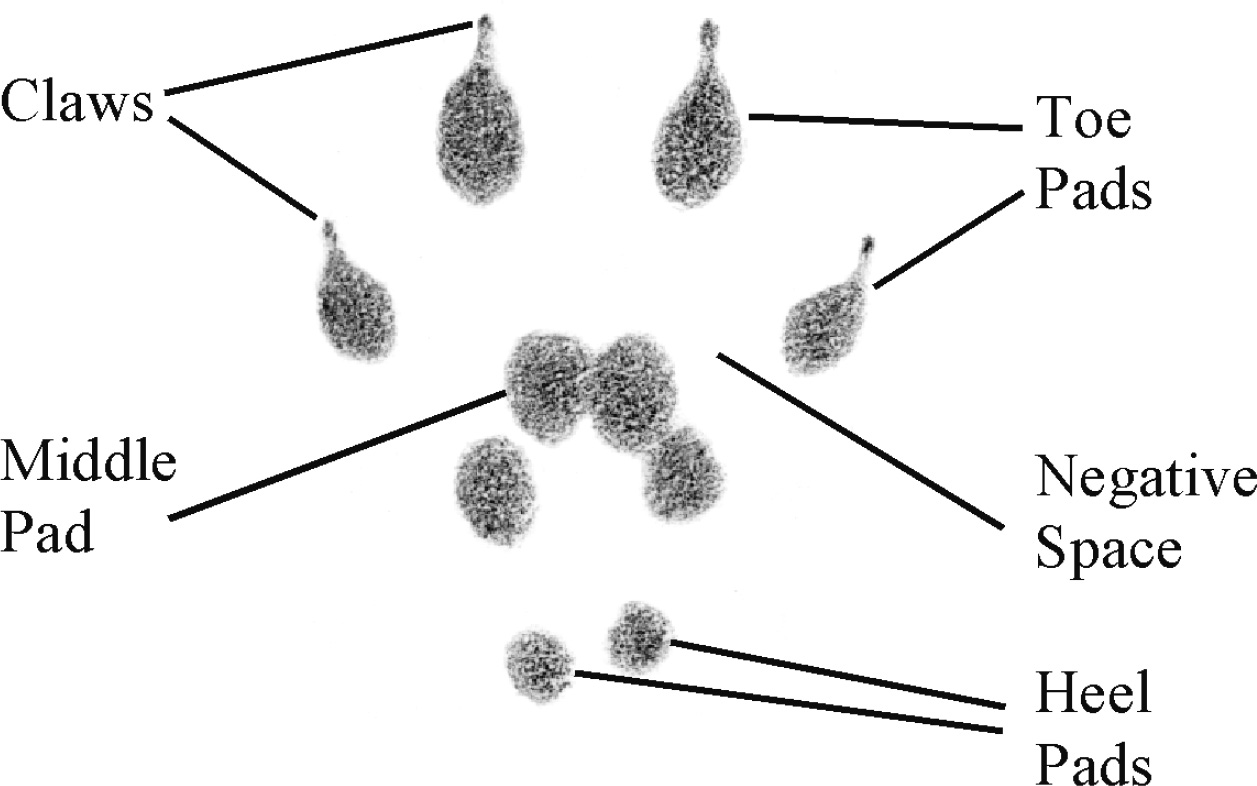

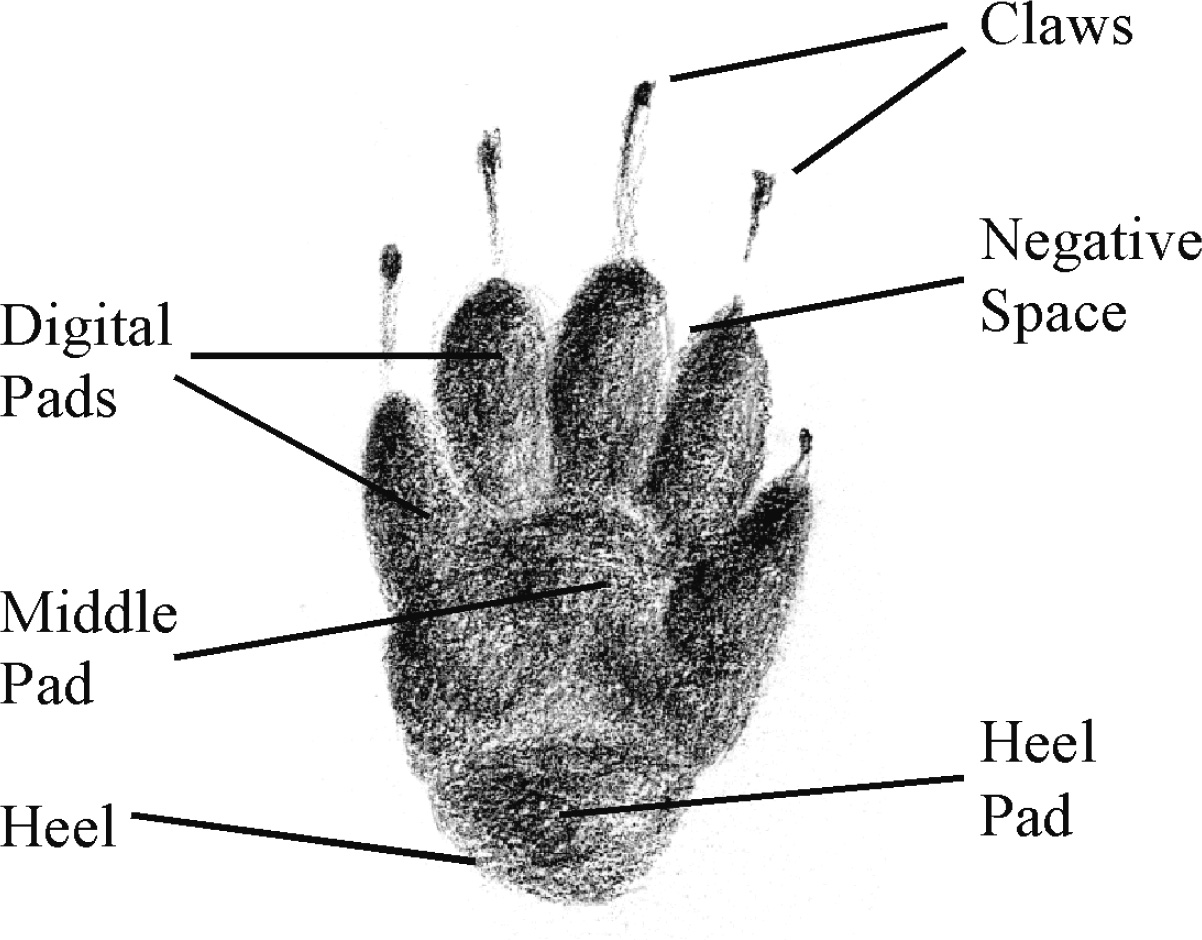

On the underside of a mammals foot there are several kinds of tough, resilient pads. Toe pads cover the distal bone of each digit, and in animals such as the chipmunk this is usually the only part of the digit that appears in the track (Figure I.1). If the entire digit normally contacts the ground, the whole length is protected by a digital pad of toughened skin. In tracks of the striped skunk, the digital pad often registers as a wide groove with an undifferentiated toe region at the tip (Figure I.2). The difference between the impressions of toe pads and digital pads is similar to the difference between the imprint of your fingertip and the imprint of your entire finger. Many animals have toe pads, including canines, felines, bears, tree squirrels, and mustelids. In their tracks, the toe impressions are usually oval or teardrop shaped and do not connect to the rest of the foot. Raccoons, muskrats, and skunks belong in the much smaller group of animals with digital pads. Their toe impressions often resemble human fingers, and their tracks may resemble human hands. But because all mammals can flex or extend their digits, the distinction between toe pads and digital pads is not always evident. The tracks of raccoons, muskrats, and skunks may not show the entire digital pad but rather oval toe impressions that are not connected to the rest of the track. In soft substrates, tracks of foxes, squirrels, and other mammals with toe pads show more of the connection between the toes and the rest of the foot.

Figure I.1 Parts of a chipmunk track.

Claws appear at the ends of the digits and their impressions can contribute to track identification. For example, the long, robust claws of skunksused for diggingshow as substantial indentations ahead of the toes (Figure I.2). The sharp, curved claws of gray foxesused for climbing and grasping preymake tiny pricks closer to the toe pads (Figure I.3).

Figure I.2 Parts of a skunk track.

Figure I.3 Parts of a gray fox track.

Middle pads support and cushion the joints between the phalanges and the metacarpal and metatarsal bones. These may be distinct knobby projections as seen in the chipmunk track (Figure I.1) or larger cushions of resilient skin as seen in the skunk track (Figure I.2). The heel area extends back to the carpal and tarsal joints. There may be one or two thickened heel pads in the area between the middle pads and the back of the heel, as you can see in the chipmunk track (Figure I.1).

All of these parts of a mammals foot may be bare or covered with hair, and the degree of hairiness can often be seen in the track. When the pads push into the ground they create indentations or hollowswhat we usually think of as the track. The areas around and between the toe pads and the middle pads are open, although they may be filled with hair. These gaps constitute the negative space and they often show in the track as ridges or mounds. The shapes and relative sizes of the pads and negative spaces vary among different animals, and the differences are important for identification. For example, in skunk tracks the digital, middle, and heel pads are packed tightly together, and there is very little negative space (Figure I.2). In gray fox tracks the toe and middle pads are separated by significant negative spaces (Figure I.3).

Next page