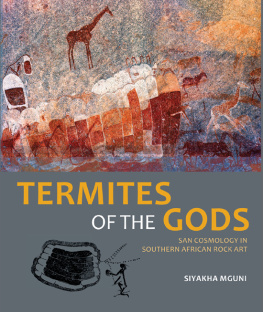

Termites of the Gods

San Cosmology in Southern African Rock Art

Siyakha Mguni

Published in South Africa by:

Wits University Press

1 Jan Smuts Avenue

Johannesburg, 2001

www.witspress.co.za

Copyright Siyakha Mguni 2015

Published edition Wits University Press 2015

Illustrations and photographs Individual copyright holders. For source and copyright of the illustrative material please refer to pg 188.

First published 2015

ISBN 978-1-86814-776-2 (print)

ISBN: 978-1-86814-777-9 (digital)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, Act 98 of 1978.

Edited by Lee Smith

Proofread by Inga Norenius

Index by Clifford Perusset

Cover design by Hothouse South Africa

Book design and layout by Hothouse South Africa

Printed and bound by Paarl Media, South Africa

To forgotten forebears of this land

Contents

Acknowledgements

I thank the University of the Witwatersrand for providing institutional and financial support for this study. I am indebted to David Lewis-Williams who encouraged me over the years. I also thank the late Peter Garlake, one of the first professional rock art researchers to support my formling interpretations. I am grateful to my early fieldwork mentors, the late Edward Sibindi and Kemesi Ncube, both of whom I remember fondly. I extend my gratitude to other colleagues and friends for encouraging my research interest, particularly Janette Deacon, David Morris, Tilman Lenssen-Erz, Catherine Namono, Selma Nangolo and Getrude Seabela. I thank especially my deceased friend Edward Eastwood who encouraged me in my efforts over many years; I recall with fondness several outings together to look for rock art sites and paintings of formlings in northern South Africa. I had numerous enriching interactions with many people over the years; although I do not have space to mention them individually, I thank them sincerely. I extend my gratitude to various people who have helped with various aspects of the preparation of this book.

Finally, I extend my heartfelt thanks to my family, amaZizi amahle, especially my parents; Susan and Jacob; Norman, Bhekinhlanhla, Banele, Nobandile, Sakhile, Sesuthu and Lwandle and others in my extended network for their unwavering encouragement and support over the years. Thando Fuzane, thank you for being my pillar of support. I reserve special recognition for an important fragment of my lineage the silent Bushman line that has ironically remained unknown by either name or surname. I have heard a repeated family legend about my great-grandfather, Mtshede Mzizi Mguni, who in his advanced old age lamented time and time again when he was emotional or upset, that he missed his mother a Bushwoman. He would proudly and nostalgically exclaim: Ngiyinkonyane yeSili! (Im a Bushman offspring). Although he said this with pride and reverence, the word iSili (pl. amaSili) is an inherited disparaging moniker with dubious etymology. However, its widespread use in western Zimbabwe today as a generic KhoeSan ethnic appellation means that it has been rehabilitated or has simply lost its negative connotations. In some ways descendants of amaSili can be regarded as secret KhoeSan in Zimbabwe few openly embrace this identity because of the unflattering history associated with their culture. Nevertheless, I trust in the belief that my great-grandfather and his San mother would have been proud of the journey I have made in the study of their cultural legacy. This study has been a satisfying and academically worthwhile personal voyage of self-discovery.

Foreword

David Lewis-Williams

Rightly, Siyakha Mguni, the author of this beautiful and stimulating book, feels that he has uncovered certain hidden mysteries of the San spiritual universe. Modestly, but again rightly, he adds that he has likely only partially uncovered the possible layers of symbolism of his chosen foci the so-called formlings and trees, two hitherto little understood components of a fascinating southern African art.

Insights of this importance do not come suddenly and out of nowhere. Rather, they are milestones along a road with many ups and downs. Discovery, it is said, favours the prepared mind. Mind preparation itself is a long and sometimes arduous task. Siyakha gives us glimpses of his journey, which began in 1978 in the Matopo Hills of Zimbabwe, a beautiful region of southern Africa that has been marked by terror and violent clashes as well as delicate images from a bygone age. He found that the place and its tranquil ambience evoke deep time.

In such situations it is easy to surrender oneself to the contemplation of beauty and also to the puzzles that the more enigmatic images imply. For some, it is almost sacrilege to probe for and expose hidden mysteries. Are we trespassing on sacred ground, intruding into the innermost thoughts of long gone people? Should we not simply allow the mystery to endure?

Siyakhas personal journey has enabled him to bridge what some people see as a dichotomy. He can, and we feel it on page after page, marvel at the subtlety of thought and beauty of line that we see in the paintings he has chosen for reproduction and, at the same time, lead us to an understanding of what the images meant for those who made them so long ago. Knowledge of how a flower works botanically need not erase our sense of wonder. On the contrary, our wonder grows as we learn more and more.

In this book, Siyakhas flowers are rock art images that are prominent in Zimbabwe but enigmatic. Some are oval patches of paint, sometimes joined in long lines; several have added details. These are the so-called formlings. Believing that the art was a direct representation of what the San saw around them, some earlier writers thought the oval forms depicted the Victoria Falls, grain bins, shields or other objects that people saw daily.

It is, however, in the rock art details that Siyakha finds answers, as has been the experience of other southern African researchers as well. The art must be viewed close up, not from afar as many Western paintings usually are. Close-up viewing raises the issue of the difference between looking and seeing. So many people look at San rock art but see very little. They find its complexity and apparent jumble on the rock face alienating.

This is where the prepared mind should take over. Leaving behind Western concepts of art and composition, viewers should seek another perspective which is what Siyakha does. He has prepared his mind by familiarising himself with the San way of life and thought as recorded in the nineteenth-century Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd collection of verbatim texts, and also with the more recent and abundant records that, especially since the 1950s, have come from the Kalahari Desert. The fit between these two sources of information is complex: they are not identical, but anthropologists have drawn attention to areas of belief that, despite various differences, display remarkable parallels. Setting San rock art in this San milieu is obviously essential. I emphasise obviously because it is not obvious to some viewers of the images. For them the art is interesting only in those ways in which they think (probably incorrectly) it parallels Western art. San rock art must be set in the context of San thought and belief.

However, that is not all. Siyakha has gone further and explored relevant zoological and entomological literature. Here he has found information that is unknown to many modern viewers of the images. But it would have been familiar to the San. It is commonplace today to say that the San lived close to nature. Yes and no. Animal behaviour, the transforming lives of insects all this would surely have been familiar to them. But they were not part of nature, as the romantic view of them has it. To their detriment, they have been seen so much as a part of nature that their stature in coping with our modern economic world has been ignored.

Next page