Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR MINA

When we come under the spell of the deeper domain of [technology], its economic character and even its power aspect fascinate us less than its playful side. This playful feature manifests itself more clearly in small things than in the gigantic works of our world. The crude observer can only be impressed by large quantitieschiefly when they are in motionand yet there are as many organs in a fly as in a leviathan.

ERNST J NGER , TH E G LASS BEES

ARIZONA

I N JULY 2008, I RENTED a small yellow car in Tucson, Arizona, and drove it south toward Tombstone. There were three passengers in my car, and I was following a white van with government plates carrying nine more. Between these two vehicles we had eleven microbial geneticists from six countries with nearly three hundred years of collective education. We also had five hundred plastic bags, a thermos of dry ice, and three hundred fifty cryogenic vials, each the size and shape of a pencil stub. We had two days to get ten thousand termites.

I was there because Id received an email titled Termite Safari? from Phil Hugenholtz, a researcher at the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (JGI). Earlier that year Id done a story for The Atlantic about Phil and thirty-eight other scientists who sequenced a million genes from the microbes found in the guts of Nasutitermes corniger termites theyd found in trees in Costa Rica. Because termites are famously good at eating wood, the genes in their guts were attractive to government labs trying to turn wood and grass into fuel: grassoline. The white van and the geneticists all belonged to JGI.

As I drove, the price of gasoline was more than four dollars a gallon, the highest it had ever been. The country, maybe the world, was spinning into a financial crisis, and a vicious presidential race was on. In those days, gasoline was always on my mind because Id written a book about oil. When I received Phils email, I had been writing about the problems of petroleum for seven years, and I was staring at twenty open PDFs about energy on my computers desktop. I was at the end of my rope, both as an oil-consuming citizen and as a human being. Oils troubles are systemic, dating back at least a hundred yearsand theyre made much nastier by modern politics. Termite Safari? Sure! Anything was better than sitting at my desk and thinking about oil.

Microbial geneticists are young and goofy: they sincerely believe in the scientific method and they blink in the sun. Phil, who led the lab with a jangly self-deprecating pride, called them gene jockeys. They lived in statistics and databases and thought in codes, both computer and genetic. Their organization was so antihierarchical that I sometimes had to tell them to stop bickering. Stop it or Ill turn this car right around, Id say.

Left on their own, the geneticists would never find ten thousand termites. They might not even find one hundred. North American termites are cryptic in the extreme: they live in tunnels underground and inside wood. So Rudi Scheffrahn, one of the countrys leading termite experts, sat in the passenger seat next to me, charting a course to the bugs.

He wore bifocals over his sunglasses while he scoured the last survey of termites in the area, published in 1934, around the time of the building of the Hoover Dam. Funded by a sugar refiner, along with lumber, railway, and electric companies, the survey hired entomologists to figure out which bugs might try to eat the electrical poles, bridges, and railway trestles that industry was erecting across California, Nevada, Arizona, and Mexico.

When Rudi sensed termites in the landscape, his sunburned knees began to twitch, which jiggled his head, sending little triangles of reflected light from his two pairs of glasses ricocheting around the rental car. It felt like a party.

When there were no termites, he seemed depressed. We drove past a lake. Probably a nice place, he said, in a flat, declining tone. But theres no termites there.

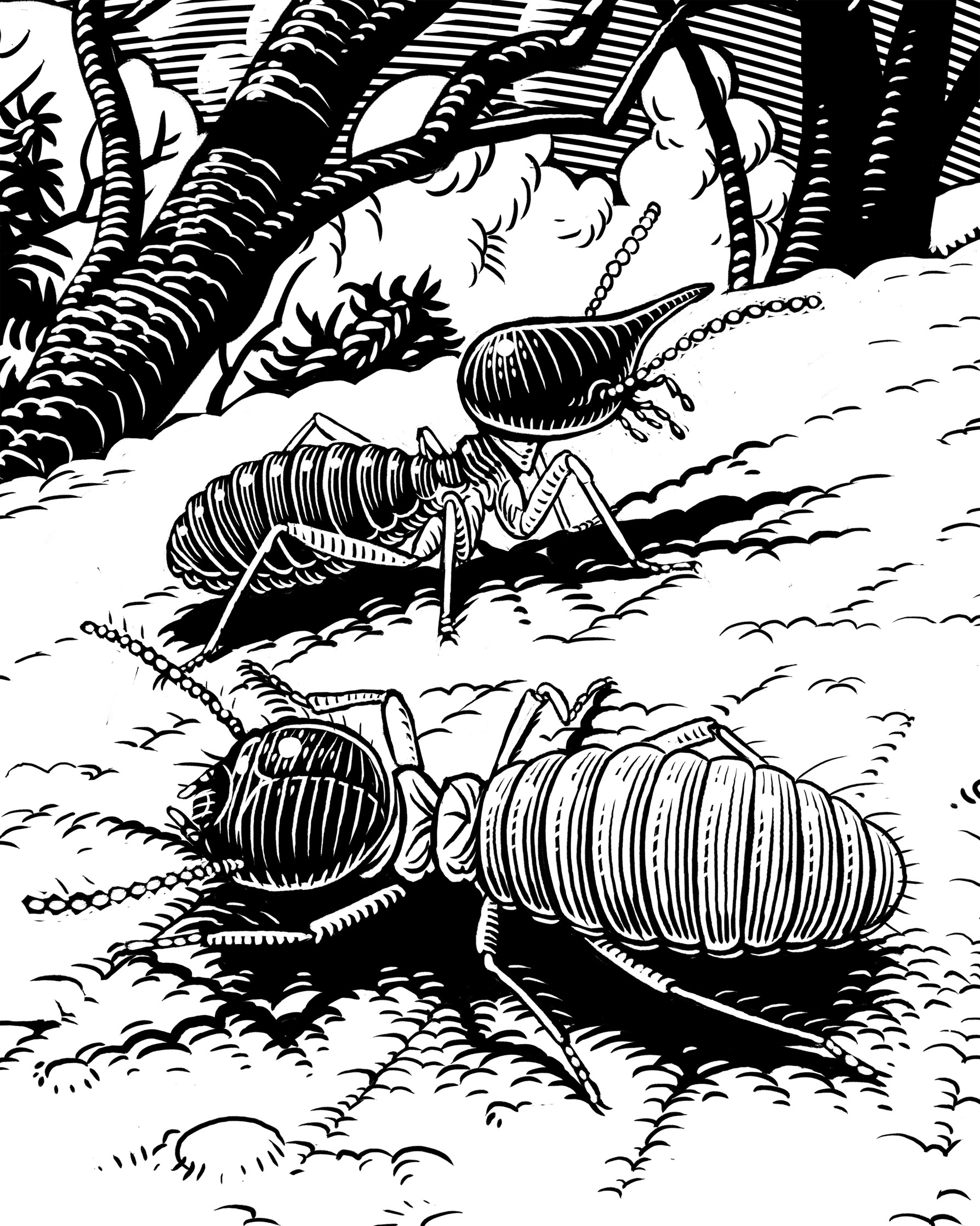

Rudi is a termite chauvinist. He talked world records. Oldest insect: termite queens can live to be twenty-five years old, maybe more, no one knows. Fastest animal: some soldier termites slam their mandibles shut at 120 miles an hour, faster than a cheetah runs. Biggest terrestrial structures: mounds in Africa, Asia, and Australia can be up to thirty feet high. And about termites reputation as pests? Only twenty-eight out of twenty-eight hundred species are invasive pests, and Rudi believes that the first destructive drywood termites traveled from Peru on Spanish ships in the 1500s. Not their fault.

The geneticists in the back of the car laughed politely. They were not here to appreciate termites; they were here to appropriate them. Termite guts are a molecular treasure chest: 90 percent of the organisms in them are found nowhere else on Earth. The purpose of this trip was to gather the termites and their microbial mush in the vials and jam them into the dry ice before the genetic information they held deteriorated. The geneticists didnt just want the microbes DNA, they also wanted the molecules of RNA, which could tell them which parts of the genetic code were in use at the precise moment the termites took their tumble into the thermos. Perhaps by seeing exactly how termites break down wood, wed be able to do it, too.

If this trip succeeded in capturing a few good molecular moments, humans might eventually be able to power our cars without worsening climate change, or make fuel without drilling in national parks or causing oil spills. This trip could change the worldor at least the lives of the scientists in the cars.

We barreled down a long hill toward a scrub basin when Rudis legs began to twitch. The reflections from his glasses whizzed around the interior of the car. I look out here and I just see billions of termites.

* * *

JUST BEFORE I got interested in termites, they lost the identitythe distinctive order Isopterathat theyd had for the last 175 years. In 2007 a paper was published called Death of an Order: A Comprehensive Molecular Phylogenetic Study Confirms That Termites Are Eusocial Cockroaches. And just like that, termites became homeless and nameless, demoted to gregarious cockroaches, very distant cousins of the praying mantis. Maybe more important, they were suddenly defined not by what they looked like, but by their genes. Their relationship to the most despised of bugs wasnt news: it was first explored in the 1920s, and became obvious with DNA sequencing by 2000 or so, but it wasnt considered a fact until 2007.

Heres a possible story of how termites came to beand why we were chasing them across Arizona. Once upon a time, cockroaches were solitary scavengers that ate fruit, rotten leaves, fungi, and bird droppings. They developed their eggs in beautiful bean-like sacs, shot them out their backsides at high speeds, and walked away, leaving their young to fend for themselves.