ALSO BY JAYNE ANNE PHILLIPS

MotherKind Shelter Fast Lanes Machine Dreams

Black Tickets

LIMITED EDITIONS

The Secret Country How Mickey Made It Counting Sweethearts

for Elie (19742005),

for Audrey (Boulder, 1975),

and for Cho,

infant boy born and died

in the tunnel at No Gun Ri,

July 1950

GIs corrupted the native term hanguk saram, which means Korean, into the derisive slang gook, which was indelicately applied to all Asians, even in later undeclared wars.

ROBERT J. DVORCHAK,

Battle for Korea

Because no battle is ever won he said. They are not even fought. The field only reveals to man his own folly and despair, and victory is an illusion of philosophers and fools.

WILLIAM FAULKNER,

The Sound and the Fury

Is your mouth a little weak When you open it to speak, are you smart?

LORENZ HART AND RICHARD RODGERS,

My Funny Valentine, from Babes in Arms, 1936

Contents

July 26

North Chungchong Province, South Korea

JULY 26, 1950

Corporal Robert Leavitt

24th Infantry Division

Hed shipped out to Occupied Japan in December 49; whatever baby was a tucked seed inside Lolas sex, a nub the size of a tail-bone. You want to marry me? You going to tell your mother who youre marrying? His mother wouldnt care, he told her, his mother was dead, he wanted a woman whod been around, he wanted her, hed got her and he wasnt leaving her, he never would, not really, was she hearing him? I hear you, Im hearing you. Mother may I, mother me. Left you too soon, didnt she. Left you to me. But hes gone from Lola now, gone for months; the baby is inside her, cushioned and pure, isolate. Winter at the base in Tokyo was like clocking a job in uniform, all of Occupied Japan an American colony with its own clubs and bars. Tokyo felt fake, soft, a movie set. When Colonel MacDowell invited select soldiers to learn Korean in a pet project he called Language Immersion Seoul, Leavitt said yes to minimal advancement and a change of duty. He was in Korea by April, one of sixty LIS army enlisted men installed at KMAG. Korean Military Advisory Group was a remnant: a few hundred army brass and their support staff of minions and enlisted men. Theyd nothing to do but stay put, a supposed symbol of preparedness overseeing largely symbolic Republic of Korea troops. Leavitt imagined his baby moving in a fluid, muscular nest he couldnt touch or feel while the American military flexed its own small fist in divided territory, but KMAGs isolated outpost disappeared the June morning North Korea invaded. Four weeks of near-constant combat since are a continuous day and night bled into Leavitts brain. Battle and the mayhem of retreat have changed the taste of his saliva and the smell of his sweat, but late July is Lolas time. Any hour, any moment. If the baby was already born, an armed forces telegram might follow Leavitt for weeks across the rutted fields and dirt roads of this bloody rout. He tells himself he wont need any telegram. Lolas voice drifts close unbidden and its like shes standing in the war next to him. No matter how loud the ordnance or artillery, how loud his own heart hammers, he hears her. Words she said when he could touch her. You found your mother because she wanted you to. All those years, her asthma pulled the air from that little store while your father stood in the doorway. She wanted you out of there.

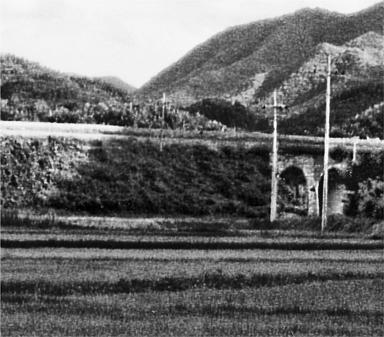

He keeps moving. Near noon of this infernally hot day, Lolas voice moves him forward. Two or three emptied villages in the immediate area constitute Leavitts detail: evacuation of refugees whose unrecorded exodus proceeds apace with the American retreat. These double train tracks running west to Hwanggan are a godsend, boundary and direction for what is otherwise panicked flight and chaos. Replacements under Leavitts command are soft recruits from Occupation forces in Japan, rushed in by boat and train to reinforce besieged American troops. Most have never seen combat or heard artillery fire. Theyre raw troops moved out at first light into countryside mired in another century. Rifle fire punctuates the darkness before and behind them; theyve heard the terms circular front and infiltrators war;" theyre sleepless and jumpy and theyre right to be scared. Many of them will die before Leavitt can teach them a thing. He has nothing to teach the Koreans in his charge, but the urgent crowd of two or three hundred thins and lengthens to a moving column once Leavitt signals the platoon to direct them off the road, onto the tracks. Easier here, a semblance of control, but theres no evacuation possible, certainly none directed by Americans. No numbered Hangul signatures in someones logbook. No logbook. Everything in South Korea is clogged or broken. Equipment shipped quickly from American bases in Japan is constantly displaced; troop movement maddeningly slowed by refugees streaming away from the fighting. The South Korean inhabitants of numberless rural villages flee behind whatever resistance American troops can offer, their mud-wattle houses left empty, outdoor cooking fires still warm. There are conflicting accounts: Chinese Yaks or American F-8os strafed the area last night in advance of troop movement. Thatch roofs, saturated by weeks of rain, burn wet and smoky once theyre set afire. Smoke veils the air like souls in drifting suspension, declining the wars insistence everyone move on.

The heat is dense, thick, and the rice fields at dawn are bright green emanations, alive with the sick fragrance they call night soil. Piled waste from countless country latrines, shoveled into pails and buckets and leaky ox carts, fertilizes the earth to yield and yield until the fields themselves are night. The spongy ground sinks underfoot, ripened and dark as any fermented secret. The ground breathes. Decay held still too long, Leavitt thinks. He keeps moving. Lola talks to him. Nothing is wasted, nothing is waste. You think you didnt need to know exactly what you know? How many boys your age blow a horn like you can and then enlist in peacetime? You wanted out of Philly mighty bad. Philly is gone. Villages here are encampments sunk in a time before radios or jeeps, before horns or jazz or English words. Skinny, wary dogs wolf any shred of slaughtered chicken, duck, fish gut dropped to the ground while women tend outdoor fires and infants slung in cloth podaegi ride the backs of girls. Older babies stagger across the patches of ground reserved each habitation and squat when they like, teaching themselves, their trousers cut out so the cheeks of their asses plump like cleft fruit. Now those babies are gathered up, quiet in the heat. Lola says lines from the beginning, like they can start all over. You know me now, dont you. Say you do. Whisper. Shes his own phantom, a smoke drifting close to him. The war makes ghosts of them all. Fifty years, a hundred years, theyll still be here: vestige mist moving along a double rail bed near a wobble of a stream, the South Koreans in their white clothes, the GIs in mud-crusted khaki.

Since Osan, Leavitt doesnt think beyond the war. Osan was July 5; Leavitt knows it was a Wednesdayhe wrote the date and day on a letter to Lola the morning of the attack. Forty-eight hours later, one of three survivors in his group, Leavitt moved to another platoon. He moved to another, then another, moving up incrementally in rank as his superiors were killed and not replaced. He commands a platoon now and he sees that war never ends; its all one war despite players or location, war that sleeps dormant for years or months, then erupts and lifts its flaming head to find regimes changed, topography altered, weaponry recast. The Red Chinese and the NKPA are only the latest aggressors to pour across Korea like a death tide. Leavitt imagines thousands of war dead, disbelieving their own deaths, continuing to die and die on the same swaths of contested land. The American troops press on through heavy air, discounting their apprehensions as vague scent, cloud scrim, their own shot nerves, but Leavitt senses the dead furling like smoke from the vented earth, wandering the same ground as the living. Any American who stood at Osan and Chochiwon, at Kum River, should be dead. The majority are dead. Korea is choked with phantoms who will never get home. The Koreans themselves are phantoms, moving with their bundles and baskets, their children, their old people.