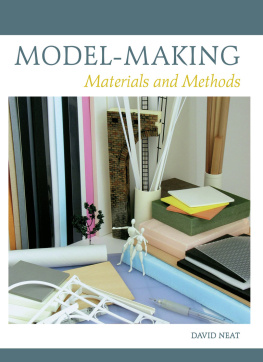

MODEL-MAKING

Materials and Methods

DAVID NEAT

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ASTRID BRNDAL

First published in 2008 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

This impression 2010

David Neat 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 729 8

Dedication

This book is dedicated to: my parents, Barbara and Wilf,

my dear brother Tim,

and to Astrid, with also such gratitude for her expert help and patience.

Acknowledgements

Staff and students at Rose Bruford College, Kent and Wimbledon College of Art, London are gratefully acknowledged, in particular Iona McLeish: Theatre Design Programme, Rose Bruford College and Chris Dyer: Wimbledon College of Art. The author would also like to thank 4D Modelshop, London; the Arts Institute at Bournemouth and Martina von Holn.

Illustration credits

David Lazenby, Lazenby Design Associates (www.lazenbydesign.com), Astrid Brndal (www.baerndal.eu), Dragonfly Models (www.dragonflymodels.co.uk), Lizzie Oxby, Charlotte Hern, Valerie Charlton, 4D Modelshop, London, Elves n Elements (www.elvesnelements.com), Dick Bird, Ben Stones, John P. Hall (www.setsmachine.co.uk), David Burrows, Marie Antikainen, Marc Steinmetz, Rachel Waterfield, Dee Conway, Richard Battye

All other photos are by Astrid Brndal unless otherwise stated, as are all models by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Disclaimer

The information given in this book is either tested through experience or to the authors best knowledge, but neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any resulting injury, damage or loss to either persons or property. Efforts have been made to ensure safety but the proper health and safety guidelines for each material featured should be consulted independently.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

The making of small forms

In many ways, this book is about the making of small forms regardless of their purpose. It is dedicated to providing technical assistance to those who, for whatever reason, have to work at that level of intricacy where the fingers (and perhaps also the brain!) find it difficult to cope. It considers the range of materials which could be used to make such small work, how these will behave and how those properties can be manipulated to make life easier. It is divided into chapters which follow the process of making; from planning and building, through ways of creating surfaces, to final painting and finish.

If this were a book about small sculpture, on the other hand, it would probably be more interested in artistic context. It might dwell more on the aesthetic qualities of form, the integrity of the medium and the longevity of the message. This book concerns itself far less with the question of what is created, more with the question of how. It considers any material as worthy, however base, impure, cheap or discarded others might view it. It will hardly ever recommend a material for the purpose for which it was intended! It will be content to advocate a fragile and temporary lifespan as long as the outcome will perform for as long as its meant to. Sometimes the real outcome is not even the object itself, but the knowledge gained by making it; the discovery of the process.

Also, if this were a book about small sculpture, its bias to wards realism might be off-putting. It encourages a slavish attention to how real things look. It leaves abstraction, simplification or stylistic licence aside, as decisions for the individual, and considers them only insofar as they might enhance the sense of the real. In that sense, this book is quite traditional, believing that one can only convey truth by being firmly founded on the appearance of the real. But leaving that debate aside, the practical reason for staying with the real throughout these pages is simply that there is no better way for the reader to be able to judge the effectiveness of the examples and methods shown.

So, in its dedication to the effectiveness of the real, youll find this book follows a fairly disciplined adherence to proportion and scale, not only for structures but also for textures, and suggests methods that will help in keeping to them. It advocates, for example, using natural processes to mimic nature, making the materials do most of the work at a level of detail which usually defies the scalpel or the brush. It questions the assumptions we often make based on how we think something looks, rather than acknowledging what we are actually seeing or taking the trouble to find out.

REALISM

Reality is a universally shared language. Models can make full use of that, relying on that shared language for their effectiveness and appeal. A sense of how things should look is so embedded within all of us that we can be affected by the most subtle of changes or the slightest variance in scale without even being conscious of it. Yet the fact that this sense is so embedded may also be the reason why it is often so difficult to see objectively what it is that makes something look so real and to recreate that quality in something artificial. That difficulty in consciously seeing may explain why such a familiar form as the human head can become so elusive when we try to model it. Yet we are so fine-tuned in recognition of the essentials that we can spot the contours of a familiar face amongst a crowd of others at a surprising distance.

Models make use of the fact that we all share a common awareness of how real things look, but they also benefit from the fact that we either dont look too closely, or are sometimes seduced by the superficial. The fact that we can be so easily fooled by the power of suggestion means that models may not have to work too hard to convince, as long as the essentials are wisely chosen. A small figure can often impress as realistic if the proportions are convincing, even though the surface treatment or lack of detail may be unnatural. On the other hand, a nondescript form can often take on the appearance of something very real by adding carefully considered details. Sometimes the essentials are in the form, sometimes in the details; most often they are provided by a combination of the two.

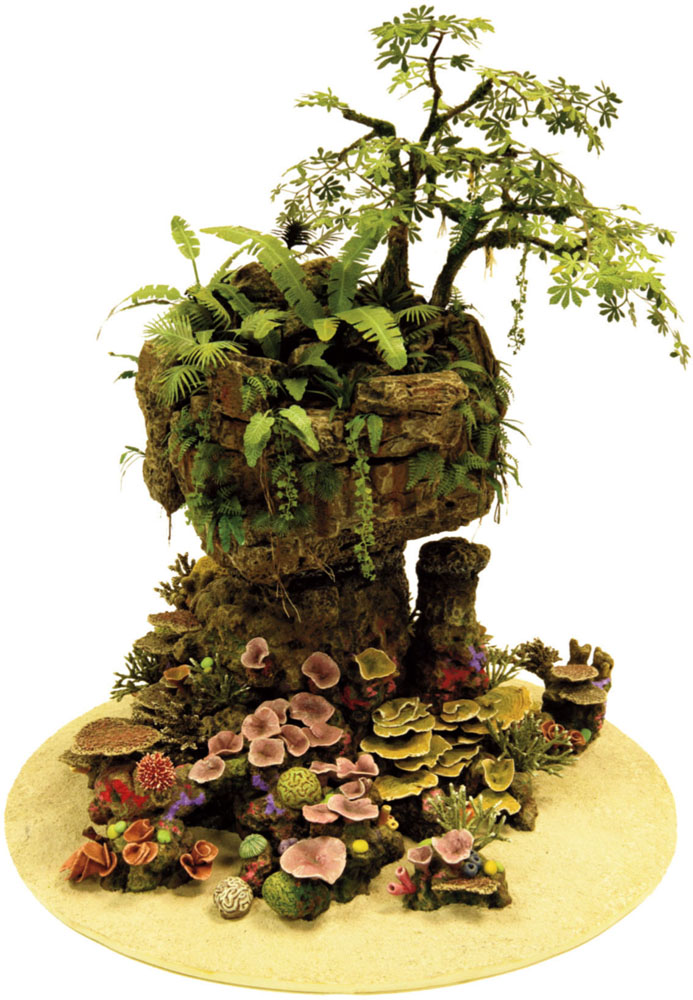

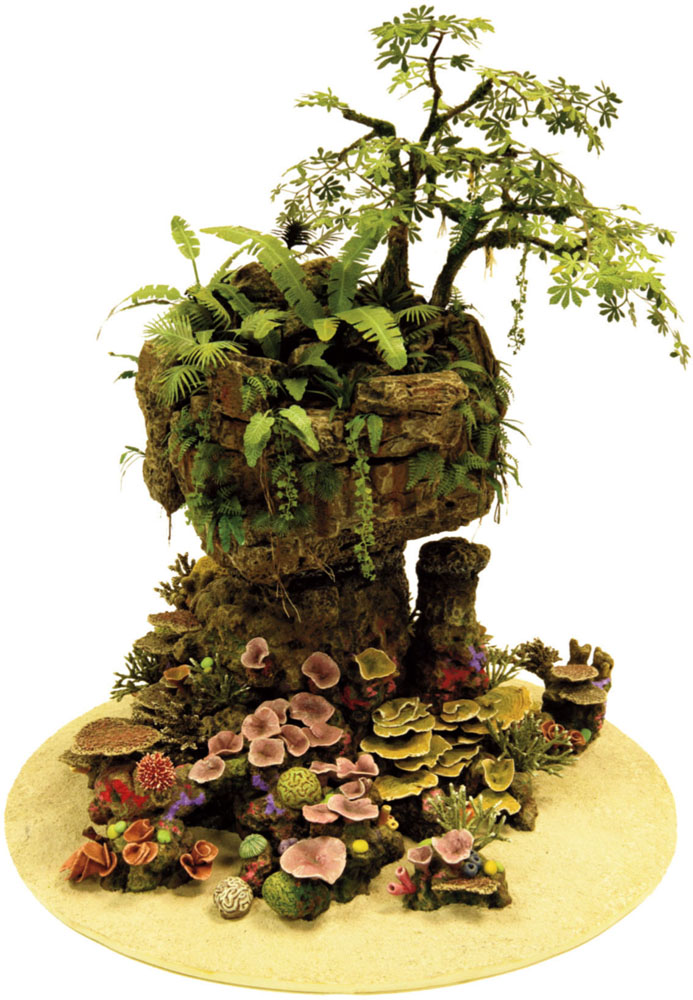

A final presentation model made by David Lazenby, whose company (Lazenby Design Associates) designs and builds environments for zoos, aquariums and museums. These models are taken to a high degree of detail and realism, enabling the fullest understanding of the intended design.

Who is this book for?

This book is intended for experienced students or beginner professionals in any discipline for which accurate scale models are required as part of the job. The bias is, admittedly, towards theatre or film model-making, because this is where most of my experience lies. But the range of model-making practised for the theatre and film can be viewed as a repository of knowledge for other fields such as architecture or interior design. By experienced students, I mean those who already have some understanding of scale, who are already fairly confident with a scalpel and who are looking for a guidebook rather than an instruction manual. But having said that, parts of this book have to be arranged like a manual simply because the techniques and material preferences of model-makers tend to become rather personal. Without a step-by-step account of some things, it might not be obvious what happens next! I have tried wherever possible to reflect recognized practice where it matters, but model-making is not exactly a long-established profession with its own regulatory guild and set of standards, so a book like this cant avoid being based more on personal experience than anything else.

Next page