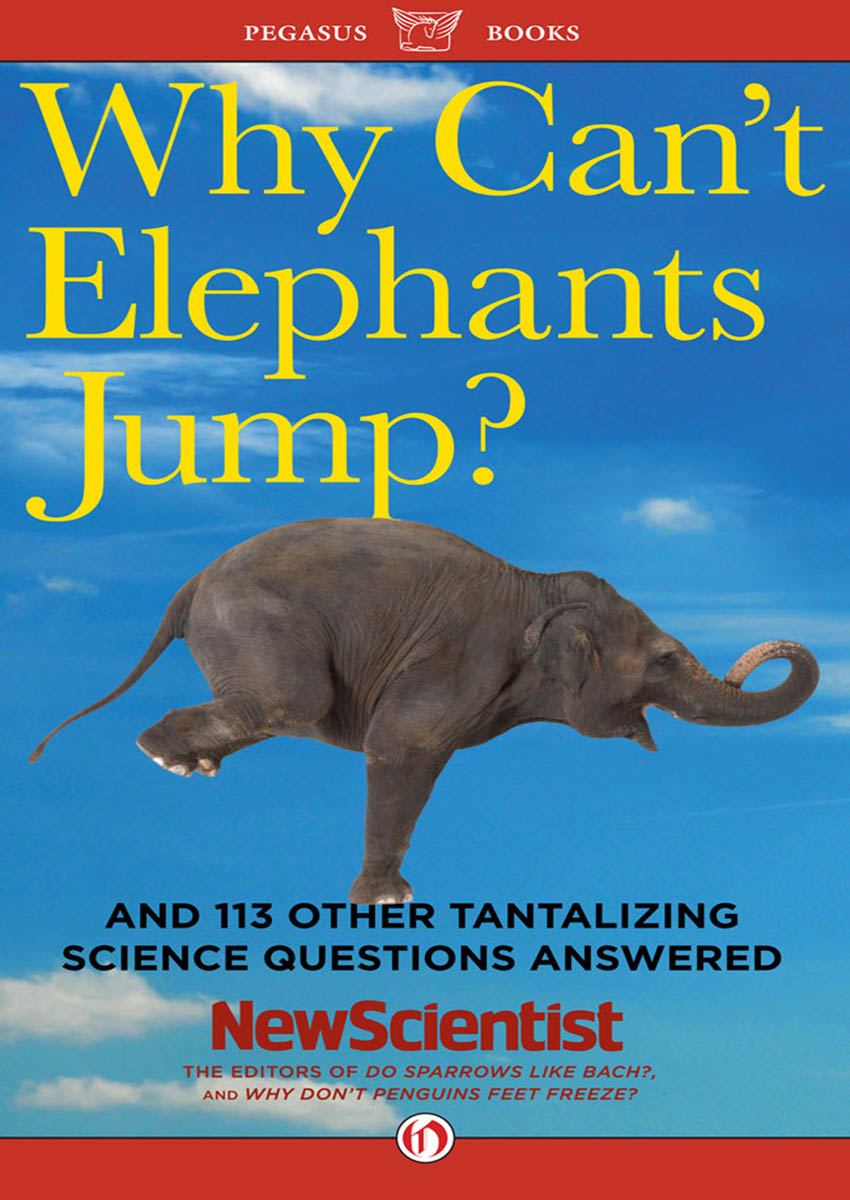

Why Cant

Elephants

Jump?

AND 113 OTHER TANTALIZING

SCIENCE QUESTIONS ANSWERED

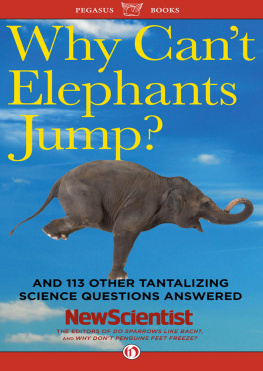

Why Cant

Elephants

Jump?

AND 113 OTHER TANTALIZING

SCIENCE QUESTIONS ANSWERED

New Scientist

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK

Contents

Introduction

Were back. And even better than before. This time were going to tell you why wet things smell more than dry things and well answer that age-old question on everybodys lips: how wise is it to pick your nose and subsequently consume what you find in there. Yes, welcome to Why Cant Elephants Jump?, the latest book in a series that began with Does Anything Eat Wasps? and had its last outing more than two years ago with Do Polar Bears Get Lonely? In this edition well reveal whether its possible to see the curvature of the Earth from anywhere on its surface (even atop Blackpool Tower) and well explain which is more tiring, walking up a slope or climbing steps.

Most of these questions began life on the Last Word page of New Scientist magazine. Each week readers pose everyday science questions while others attempt to answer them. You can join them by buying the magazine or visiting the website at www.last-word.com. But remember, you wont find anything on quantum mechanics or event horizons thats all covered by the clever New Scientist journalists elsewhere on the website and in the magazine. Instead, youll find the science of everyday things, such as why its difficult to tear sticky tape across its width. New questions are always welcomed, as is hefty debate on whether we gave the right answers to old ones. And our knowledge is growing at a rapid rate. Once upon a time we worried that the observational prowess and ingenuity of our readers would dry up now we know better, and this book is testimony to those powers.

Eagle-eyed readers will have noticed that a good few of the questions in this book just like those found in its predecessors have been answered by a Mr Jon Richfield of Somerset West, South Africa. In fact, Jons existence has been questioned by many (some speculated he was a pseudonymous stand-in for New Scientists journalists), while others have wanted to know if there is anything he cannot answer. We are delighted both to confirm his existence and to run a question that his wife tells us he doesnt know the answer to. Check out page 51.

And last of all, we are daring to go into the casino bar once more with James Bond. In previous books weve mused over what chemistry creates the difference between a shaken and a stirred vodka martini. Well, weve found out more. You expect us to talk? Well, if you insist on aiming that scary-looking laser at us, of course we will. Turn to page 6.

Enjoy the book and be inspired to join in. You could soon be the next Jon Richfield.

Mick OHare

Special thanks are due to everyone at Profile books especially Paul Forty and Valentina Zanca while Jeremy Webb, Jessica Griggs, Lucy Dodwell and the subbing team at New Scientist made sure the book is as error-free as it could be any remaining mistakes are mine alone. Judith Hurrell proved to be a tireless researcher when press-ganged into the job unexpectedly, so thanks to her. And finally thanks indeed to Sally and Thomas.

1 Food and drink

| Super food |

Is there a single foodstuff that could provide all the nutrients that a human needs to stay reasonably healthy indefinitely?

Andy Taplin

Cambridge, UK

Any single substance such as water or fat? No. Any single tissue such as muscle or potato? No. But if we allow free drinking water and air to breathe even though those are also nutrients then we can relax our rules. Even so, drinking milk while eating corn would count as two foodstuffs, and who knows how many foodstuffs pizza contains.

Not surprisingly, no strict monodiet can rival any healthily balanced diet, but there are two classes of foodstuffs that in appropriate quantities can maintain a reasonable level of health. One such class is baby food. Examples include eggs, milk, certain seeds, and so on. None is a perfect option, but some are adequate.

Alternatively one might cheat by counting essentially whole animals: oysters or fish such as whitebait or sardines might supply the necessary nutrient uptake. Animals sufficiently closely related to humans might also do, if eaten in the correct form and quantity. Farming families in the semidesert Karoo region of South Africa apparently ate mainly sheep or cattle.

For the most perfectly balanced human monodiet, however, other humans would be the logical food of choice. Not sure there would be many takers though.

Jon Richfield

Somerset West, South Africa

Despite various claims made over the years for spinach, baked beans or bananas, the answer is no. To remain healthy over the course of a natural lifetime, a human needs a balanced diet, with a combination of carbohydrates and protein and a proper range of vitamins. The balance may vary with age, from individual to individual, and even between societies in differing environments, but balance is the key to healthy eating.

Probably the most homogenous diet of any human community is that of the Inuit in Arctic North America, which traditionally consists of 90 per cent meat and fish and effectively no carbohydrates. The explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson not only established that Inuit hunters often lived for between six and nine months of the year on a wholly carnivorous diet, but also claimed to have sustained himself by eating just meat and fish on his expeditions.

In a series of controlled experiments under the auspices of The Journal of the American Medical Association, Stefansson and a number of his colleagues reproduced the dietary regime they had followed in the Arctic, without any apparent ill effects and without, much to the supervising doctors surprise, developing scurvy. However, subsequent long-term studies of health factors in the Inuit community have established a strong correlation between the carnivorous diet and early deaths among Inuit men from heart attacks and other cardiac problems.

The bottom line is to remember what your mother told you: always eat your greens.

Hadrian Jeffs

Norwich, Norfolk, UK

Humans have been suggested as the ideal diet for other humans, but eating human flesh would not satisfy all our dietary needs, no matter how healthy the diner or victim, for a very simple reason: not every nutrient, mineral and vitamin in the body remains available to the next step in the food chain. Some substances are used up and others are built into indigestible tissues and structures.

Cooking can increase the digestibility of many foodstuffs for a human, but things like hair, bones and teeth cannot be prepared to make them amenable to our digestion. However, we need the minerals, amino acids and other nutrients in them to make these substances for ourselves.

The human body is a tenacious machine and will continue to survive on a very poor diet for quite a while. Many people living in harsh climates have their own dietary supplements in local foods and delicacies that they may not even realise are making up a shortfall. The same is true of those who live in a self-imposed harsh regime, such as true vegetarians. One can live on such diets and remain healthy as long as there is a balanced variety of nutrients, or by taking artificial supplements such as vitamin B12.